Feeling Seen: Guys & Dolls

Feeling Seen is a regular column focusing on personal reflections on films from different authors and writers.

Marlon Brando and Frank Sinatra in Guys and Dolls (Joseph L. Mankiewicz, 1955)

When a movie you love crosses the threshold to become a personal favorite—the kind that you rewatch to the extent that you can anticipate the dialogue—it starts to occupy a curious place in your head as a critic. It can become a precious thing to you: impervious to critique. Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s 1955 screen adaptation of the stage play Guys & Dolls is one of those movies for me. I’d give my eyeteeth in its defense; its songs are classics, its humor cynically blackhearted, and its soundstages a Technicolor fantasia of New York. Maybe more than anything, it creates a world that feels honest without being at all a part of reality—a heightened version of a bygone mid-century Manhattan, with hucksters prowling in pinstripe suits and breaking into song.

Guys & Dolls was originally brought to the stage in 1950 by producer Cy Feuer and songwriter Frank Loesser, adapted from Damon Runyon’s short story “The Idyll of Miss Sarah Brown.” It was a hit, and when successful independent producer Sam Goldwyn saw the play he immediately became determined to make it into a picture. It was distributed by MGM and made in Cinemascope, featuring the honeyed croon of Frank Sinatra in a world of hustlers, showgirls, and old-timey gangsters. The plot revolves around two Broadway gamblers, Nathan Detroit (Sinatra) and Sky Masterson (Marlon Brando). Nathan needs money to fund his floating crap game, and he thinks he’s found a safe bet: he wagers Sky he can’t take uptight missionary worker Sarah Brown (Jean Simmons) to Havana on a date. Chaos ensues when it looks like Nathan is going to lose his bet after all.

From the first time I watched it, Guys & Dolls felt ready-made for me to love. There was the gussied up artifice of the soundstages, the glamorous costumes, the wiseguy dialogue, and my beloved Sinatra and Brando. But I also knew, even on what would be the first of many viewings, that it is a film totally ensconced in the backwards gender attitudes of its time. The titular song, after all, is an exasperated observation of men going to great lengths to please their girlfriends and wives. Or, in contemporary parlance, it’s a warning of the dangers of being pussywhipped.

Guys and Dolls (Joseph L. Mankiewicz, 1955)

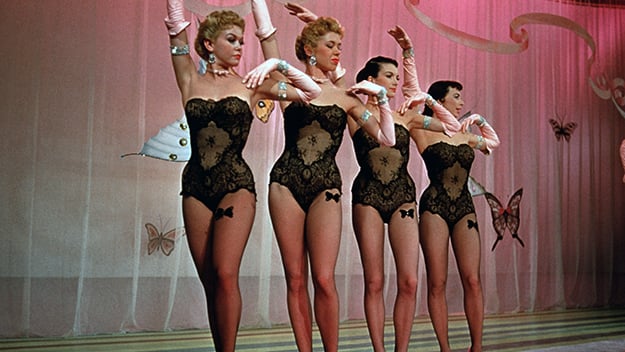

Sky tells Nathan early in the film, “A doll is something to have around when they come in handy, like a cough drop. Figuring weight or age, all dolls are the same.” Adelaide (Vivian Blaine), Nathan’s long-suffering girlfriend, is plagued by psychosomatic colds because she remains unmarried; Sarah admits she’s probably “repressed” and “a prude” before she falls for Sky. It’s not a shocking outlier or an especially outrageous example of sexism for ’50s America, but it is insidious in its own way, suggesting that single women end up maladjusted and shrill. And so, it begs the question: why am I still so blinded by the fuchsia evening gowns of the “‘Take Back Your Mink”’ sequence, a comic ode to gold-digging that implies that women will do all sorts of “favors” in order for expensive gifts? Why is Sky Masterson so indelibly attractive to me in spite of his belief that all dolls are interchangeable?

It’s easy for me to give Guys & Dolls a pass—much more so than any other movie with similar attitudes towards women. Maybe it’s because, like anyone even fleetingly interested in cinema, I’ve become used to seeing egregious and mean-spirited depictions of women—even just within the category of other Frank Sinatra musicals. Pal Joey (1957) endorses casual sexual harassment before the opening credits and shrugs off “affairs” with underage girls; by comparison, Guys & Dolls’ creaky but mostly respectful gender roles feel positively genteel.

It could also be the sheer artistry and craft that gets the movie off the hook. The songs, written by Frank Loesser, are genuine toe-tapping classics, like Stubby Kaye’s famous “Sit Down, You’re Rocking the Boat.” There’s also the fact that the movie felt a little bit like an anachronism even at the time. It was shot entirely on soundstages in the ’50s, when on-location shooting had become increasingly popular. Even other recent MGM musicals had been shot on location—including 1949’s On The Town—so to see Guys & Dolls made to be so garishly and unabashedly artificial is striking. Perhaps this is part of why the film is so well-suited for nostalgia and fantasy. Guys & Dolls’ vision of the criminality and “riffraff” of New York City is lighthearted, with an aesthetic so clean and bright that the audience is not forced to reckon with anything genuinely troubling. As a musical, it makes for a harmless repository for my own fascination with gangsters and gamblers; they’re not shown with gritty authenticity here, but as defanged, lovable antiheroes with great hats and sly remarks. Guys & Dolls makes it okay to love machismo and tough-guy posturing and old-school charm, all the things I shouldn’t like as much as I do, because it’s all so safe. And isn’t safety right at the heart of nostalgia? Loving a mythic old-timey Manhattan, with all its airless soundstages and familiar songs, is comforting for those reasons, from my perch in 2020. Nothing is safer than the past.

Guys and Dolls (Joseph L. Mankiewicz, 1955)

Another element that intrigues me is the contentious casting choice of Brando, as Sky. People invariably mention his bad singing voice when talking about Guys & Dolls. Given that Brando had just starred in Elia Kazan’s On the Waterfront—shot on the freezing dockyards of Hoboken in black and white—his jump to Guys & Dolls seems all the more drastic. As the agonized Terry Malloy, he had become known as an earthy, smoldering, gravity-shifting performer—not a singing wiseguy.

It’s an easy thing to poke fun at, especially given that Brando himself was the first to admit he wasn’t exactly a natural songbird. It’s my contention that he never should have been given “Luck be a Lady” to sing when Frank goddamn Sinatra was in the same movie, but also that Brando brings something else to the film, something unusual for a man in a musical from this era: sex appeal. With a slouchy machismo, his shoulders filling out his double-breasted pinstripe suit, Brando single-handedly ratchets up the sexual potency of the whole movie. It would be his first and last attempt at musical comedy, but his presence only further heightens the dreamlike and paradoxical nature of the movie; his authenticity is in stark contrast to the wholesome mood of a musical like this one. But if his performance chafes at all, it creates friction that’s undeniably sexy.

For me, this is best demonstrated during the musical sequence “If I Were a Bell,” where Sarah is drunk, and staggeringly advances on Brando as he playfully squares up to her and prevents her from falling over. It’s a choreographed sequence where Sarah leaps and dances and jumps, but she’s too intoxicated to do much but keep accidentally hitting her date. It’s here that Sarah finally admits that she has a terrible crush on a man she shouldn’t. The messiness and joy of it—plus the fizzing chemistry between the two—feels like more than fair compensation for Brando’s singing voice.

Jean Simmons and Marlon Brando in Guys and Dolls (Joseph L. Mankiewicz, 1955)

But beyond the anachronistic visual choices and the strange casting, what grabs me most of all about Guys & Dolls is another paradox. It was probably best voiced by Goldwyn in an interview at the time. Asked about his choice not to dub Brando and Simmons, the mega-producer said, “I wanted everything about this picture to be honest.” It seems like a strange thing to say about a film so patently artificial in look and stylized in dialogue. But Goldwyn had it right: Guys & Dolls is honest without being realistic. Its cynicism about moral righteousness and attitude about what it takes to really make a buck belongs in a much darker movie, in some respects.

In spite of the slick MGM treatment, Guys & Dolls is still Damon Runyon to the core; it wants us to laugh with and love and root for the ne’er-do-wells, because they have the real temperature of the city and maybe the world. In Runyon’s New York, everyone is on the take, and even the folks who look least like wiseguys are wised up.

In the wordless opening sequence of the film, a flurry of primary-colored activity takes place on the streets of Times Square. Mankiewicz’s camera follows tourists being pickpocketed, pretend panhandlers, bookies, snake oil salesmen, and guys with nicknames like Harry the Horse. Meanwhile, joyless Sarah and the self-righteous Lieutenant Brannigan, the cop trying to slap the gamblers in cuffs throughout the film, are targets for our scorn and laughter. We grow to like the pious Sarah more when she gets into a drunken bar brawl, and most of all when she refuses to rat on the gamblers at Nathan ’s crap game. You can choose to see this arc as a sexist one, where a woman has to sacrifice her beliefs for a man, and thus become—as gangster Big Jule calls her—a “right broad.” There might be some truth in that. But I like to see it this way: in the world of the film, there are only the hustlers and the patsies. Sarah finally wises up and crosses over to Sky and Nathan’s side. Guys & Dolls knows where the smart money is. Sky probably says it best: “Come all ye repenters. Let us bring a little sin into your life.”

Christina Newland is a writer on film, culture, and boxing, with bylines at Sight & Sound, The Guardian, and others.