Feeling Seen: Edward Yang’s Yi Yi

Feeling Seen is a regular column focusing on personal reflections on films from different authors and writers.

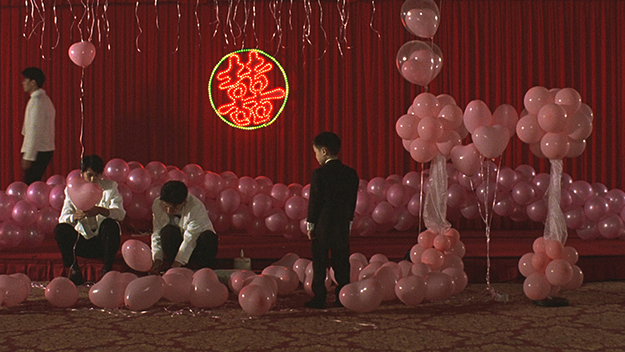

Images from Yi Yi (Edward Yang, 2000)

Edward Yang’s final feature Yi Yi is a multi-generational family drama, a plaintive city symphony, and an epic story of incalculable grief. To watch the film is to observe as the central Jian family move through the familiar rituals of life and death, to get a glimpse of Taipei’s cityscapes before the turn of the millennium, and to see the omega point of Yang’s cinema, which one could trace back through the turmoil of A Confucian Confusion (1994), the mournful anger of A Brighter Summer Day (1991), and the urban grid-like structure of The Terrorizers (1986). But to watch Yi Yi is also to witness the gradual loss of a language: though most of the film is in Mandarin, its dialogue at crucial points slips into Taiwanese Hokkien, the history of which is as fraught and contentious as that of Taiwan itself. Once spoken by a majority of the island nation’s population, the language was suppressed during Japanese occupation (1895–1945), as well as during the period of martial law that followed under the new Republic of China (1945–1987). Its continued, though waning, existence remains forever marked by those events.

In Yi Yi, it is during the lengthy opening wedding party—a celebratory stretch already marked with faint premonitions of disaster—that we first hear spoken Hokkien. Returning from a brief jaunt to McDonald’s with his eight-year-old son Yang-Yang (Jonathan Chang), NJ (Wu Nien-jen), the film’s middle-aged father figure, unexpectedly encounters Sherry (Su-Yun Ko), his estranged former lover, whom he was to marry some decades prior. As easily as they come to recognize each other, they fall back into the language of their youth. Though their bearing is reserved and their exchange halting, the scene feels exceedingly intimate nonetheless, observing the ache of years collapsed into mere seconds of screentime. Throughout it all, Yang-Yang looks on, not seeming to understand even the words being spoken.

Watching Yi Yi for the first time in 2014, however, I found that I could. Though an unremarkable fact in itself, this spark of recognition came as a singular shock. Having grown up in the Philippines, to a family with ancestral roots in China’s Fujian province, I speak a variant of Hokkien that’s not precisely the same as, though still mutually intelligible with, the Taiwanese variant spoken in Yang’s film. For me, Hokkien was the language of home and family—not a useful tongue, but a private one. To hear it spoken in Yi Yi, then, was to experience something I had previously neither sought nor missed. But this lack having thus been uncovered, it was Yang’s film that provided a measure of reassurance thereafter. A borrowed comfort, but a comfort all the same.

It would be a mistake, though, to consider Yang’s film singular in its attentions to language; one need only look to fellow Taiwanese New Wave director Hou Hsaio-hsien’s work to see (or rather hear) similar elements at play, most evidently in his 1989 historical opus A City of Sadness. But first encounters exert an undeniable pull—all the more potent for being so unexpected. (Since that viewing, only Wong Kar-Wai’s early masterpiece Days of Being Wild, which relocates to the Philippines for a lengthy stretch, has offered a similar frisson of recognition.) In Yi Yi, it is mainly NJ that speaks Hokkien: in clipped conversation at the hospital where his mother-in-law is taken early on, in bouts of frustration with his wayward brother-in-law, and, late in the film, in a tender, furtive phone call to Sherry.

An urban filmmaker of the highest order, Yang captured Taipei with an uncanny sense of proportion, an intuitive feel for how to balance his story’s sensuous rhythms and its overlapping narrative lines. In Yi Yi, his attentions to scale and distance often worked to augment the emotional valence of any given scene; his governing impulse was to render emotions not bigger than life, but commensurate to its everyday aches and longings and confusions. (In a glacéed composition of a high-rise office window, through which we see NJ’s wife Min-Min break down before a coworker, the luminous, jumbled urban landscape below becomes practically imprinted onto the scene’s tortured, fractured emotions.) Always, Yang seemed to know just where to place the camera, offering a view of an underpass from the balcony of a Taipei high-rise, or the vivid rush of a foreign cityscape from the vantage point of a speeding train.

The latter begins the Tokyo-set portion of Yi Yi, in which NJ, on the pretext of a business trip, finally reconnects with Sherry. It’s the most moving section of the film, and—not coincidentally perhaps—the stretch where the two converse most freely in Hokkien. As the middle-aged former lovers move through the Japanese city, playing out the longings of years past, Yang intermittently cuts away from their reunion to the streets of Taipei, where NJ’s 13-year-old daughter (Kelly Lee) is going on a tentative first date. Better than any other moment in Yi Yi, this passage’s mellifluous, rhythmic montage bears out the symmetry of the film’s title, which translates literally to “one by one,” and also—through the visual play of its Chinese characters—gives rise to the jazz-inflected English subtitle A One and a Two. In the scene’s syncopated juxtapositions, we feel not just the parallels between the two generations of would-be lovers, but also the gulf of difference that separates them. As we hear the two languages overlap, there’s no authorial verdict of superiority, only an acceptance of what must inevitably come to pass—for who can, in their own time, truly judge such shifts and successions? This, of course, does not preclude a sense of loss, which Yang here brings to the fore—keenly, fully.

In a director’s note for A Brighter Summer Day at the 1991 Tokyo International Film Festival, Yang writes: “It is horrifying to think that man might have deprived his own species of the truth for hundreds of years. Luckily, there are enough clues left by the great minds of the past in their art, their architecture, their music, their literature, etc., to help their future generations to somewhat reconstruct the truth and restore our faith in humanity. Films must serve the same purpose for our future generations.” Though he was referring specifically to his reasons for representing the period of his youth in the 1960s, Yang’s statement more generally speaks to the cultural shifts that his films, in their way, help to chronicle and preserve. Inasmuch as the vast canvas of Yi Yi could be said to have a single purpose, it is to draw out the sting of absence, to make a viewer truly feel an inconsolable lack—best embodied by Yang-Yang’s back-of-the-head photographs, meant to help people see what they are themselves unable to. Whether in matters of language or otherwise, this is no small achievement.

Lawrence Garcia is a Vancouver-based film writer and a frequent contributor to Cinema Scope and MUBI Notebook.