Excerpt: Movie Culture in the Age of Reagan: The Triumph of Tribalism

Do movies leave an impression? Watching the September 27 cinematic event known as the Kavanaugh Hearing, one might wonder. If you were an American kid during the season in which 15-year-old Christine Blasey encountered 17-year-old Brett “Bart” Kavanaugh and Mark Judge, you and your parents undoubtably saw E.T. If you had (or were) a hip older sibling, you might have caught the more complicated Blade Runner. But if you were a brewski-chugging body-builder, the movie of movies was Conan the Barbarian. The only movies cited on Kavanaugh’s June calendar are Rocky III, Grease II, and Poltergeist. But what about May? Herewith, respectfully offered to the Senate, the Senate Judiciary Committee, the FBI, and the American people is a brief excerpt from my forthcoming book Make My Day: Movie Culture in the Age of Reagan.

As winter turned to spring, unemployment approached 9.5%, the highest rate in 40 years. Housing foreclosures set a new record. The Census Bureau reported that 14% of American families were living in poverty, the greatest total since the late 1960s. Meanwhile, a new hero was rumbling through the land: the eponymous, muscle-bound hero of John Milius’s Conan the Barbarian.

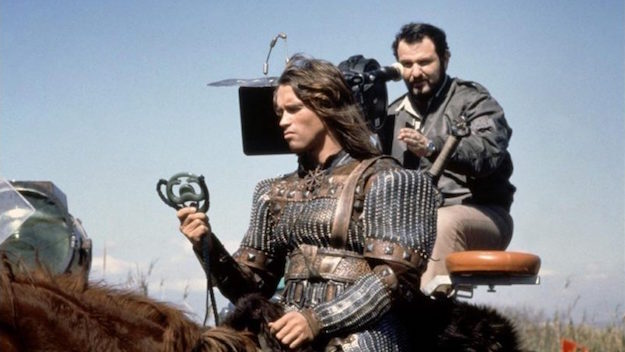

A thousand people were turned away on the night of February 19 when Milius’s film, starring body-builder Arnold Schwarzenegger as the long-haired “Hyborian Age” hired sword invented by pulp writer Robert Howard in the 1930s and, since 1970s, a Marvel comic book hero had its sneak preview. Universal hastily scheduled three screenings the next night in Las Vegas and still could not accommodate the crowds.

There were previews in 30 cities on March 12. Some precipitated total bedlam. In Los Angeles, people reportedly fought to gain admission. In New York, two capacious Broadway houses were mobbed, per Carlos Clarens in Film Comment, by “a restless, loud, volatile compound of young adults, mostly male,” police forced “to intervene and keep late-comers from crashing the already sold-out houses.” Opening on May 14, Conan grossed $9.6 million on its first weekend, and reigned as the nation’s top box office attraction for two weeks, coinciding with the height of the war between Britain and Argentina over the Falkland Islands.

The most aggressively personal of recent sword and sorcery films, Conan was a spectacle of brute violence rather than snazzy special effects, taking its cues from Alexander Nevsky, Samson and Delilah, and Triumph of the Will. Schwarzenegger would tell the press that professionally bellicose Milius ran the set in mock military fashion, complete with “Nazi salutes,” drills, and “General Milius” inscribed on the back of his director’s chair. Nothing if not gung ho, Milius presented Schwarzenegger as the ubermensch embodiment of paranoid individualism and the Nietzschean will to power. (Nietzsche is invoked at the onset with a quote filtered through Watergate burglar G. Gordon Liddy: “That which does not kill us makes us stronger.”)

Even more than his buddy George Lucas, Milius proposed to elevate a 12-year-old’s Saturday matinee epiphany into a world religion although, when Conan prays to his god Crom for victory and, by way of amen, adds “if you do not listen, then the hell with you!” he seems more the apostle of secular super-humanism.

Indeed, like Ayn Rand who might well have enjoyed the movie, Conan is markedly anti-religious. The arch villain Thulsa Doom (James Earl Jones in a braided Beatle wig) is a cult leader whose temple was said to be the largest free-standing set in Hollywood history and whose hippie followers are ready to commit mass suicide if so commanded. It is also anti-urban, as when Conan first visits the degenerate city of Zamora, and—given its phallocratic adoration of the loincloth-clad muscle man—strategically homophobic as when Conan violently rebuffs an advance made by Doom’s swishy priest.

Reviews were mixed. Many deemed Conan a ludicrously violent and pompous cartoon. (The editors of Mad magazine evidently regarded it as so outlandish that, rather than their master caricaturist Mort Drucker, they assigned their “maddest” cartoonist Don Martin to illustrate “Conehead the Barbituate.”) Milius “treats the material as solemnly as if it were an authentic Norse myth or Icelandic saga,” New York magazine critic David Denby wrote. Perhaps because of Schwarzenegger, or Milius’s Wagnerian pretentions, or both, Conan had the best opening in West German history, topping the World War II submarine drama Das Boot both in its first week admissions and grosses.

Denby was one of the few critics to address Milius’s ideology (“Milius worships force, but he doesn’t have the consistency or the visual skills to be a good fascist filmmaker”) although this would soon be commonplace. Some years later, in his book From Vietnam to Reagan, Robin Wood would call Conan the lone 1980s fantasy film to “dispense with a liberal cloak, parading its Fascism shamelessly in instantly recognizable popular signifiers: it opens with a quotation from Nietzsche, has the spirit of its dead heroine leap to the rescue at the climax as a Wagnerian Valkyrie, and in between unabashedly celebrates the Aryan male physique with a single-mindedness that would have delighted Leni Riefenstahl.

Schwarzenegger himself had Republican politics. He was a vocal Reagan supporter as People magazine pointed out in a June profile that, although pegged to Conan, seemed mainly interested in the body-builder’s romantic relationship with the TV news personality Maria Shriver, Senator Ted Kennedy’s niece.

Indeed, Conan was the first of the Reagan Era’s “hard body” protagonists identified by the academic Susan Jeffords in her book of the same title a dozen years later as a palliative to the nation’s still-smarting defeat in Vietnam. The Schwarzenegger torso was crucial and some reviewers associated Conan with Jane Fonda’s Workout, just released and soon to become the year’s top-selling VHS tape.

Schwarzenegger himself regarded Conan as the new Rocky, telling The New York Post that “the picture is a winner because Conan is a winner… He’s the kind of person an audience can identify with. He never gives up.”

Never give up! Never admit! Schwarzenegger went on to be the personification of hyborian hypermasculinity—the antithesis of the “girlie men” mocked by his Saturday Night Live imitator Dana Carvey. And Conan the Barbarian has remained something of a sacred bro text for the alt.right and others.

Conan’s tribalist declaration that a man’s greatest joy is “to crush your enemies, to see them driven before you, and to hear the lamentations of their women,” is a T-shirt evergreen. With hours of Senator Lindsey Graham’s tantrum during the Kavanaugh hearings, a member of Reddit’s Trump discussion group had grafted the senator’s snarling face on Conan’s imposing torso.

J. Hoberman is a New York–based film and culture critic, currently teaching at Columbia University, and a contributing editor to Film Comment.