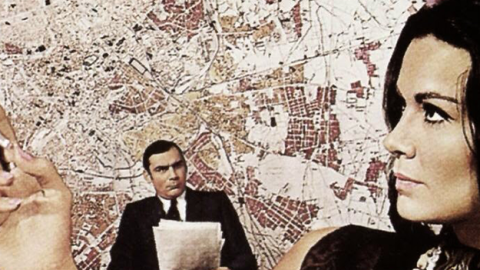

Deep Focus: Sicilian Ghost Story

At a rare peak of bliss in Fabio Grassadonia and Antonio Piazza’s gritty fantasia Sicilian Ghost Story, the 13-year-old hero, Giuseppe (Gaetano Fernandez), who looks dashing riding horseback in his jodhpurs, accepts a love letter in a hand-decorated envelope from Luna (Julia Jedlikowska), his most artistic classmate. He seals it with a kiss; Luna stops the smooch with giggles. Yet it carries an emotional punch greater than the melodramatic clinches of most adult crime, horror, or message movies. Sicilian Ghost Story melds elements of all three into a poignant, rapturous panorama of imperiled youth triumphing—albeit partway—over malice and corruption. This insidiously unsettling, genuinely haunting film captures the latent evil within a sun-kissed Sicilian town and the natural and supernatural shocks and wonders that permeate the deep forest beyond. It is by far the best trip the recent cinema has taken “into the woods.”

Grassadonia and Piazza spin their fictional plot from a terrible real crime: the 1993 Cosa Nostra kidnapping of Giuseppe Di Matteo, whose father had gone into hiding as a “supergrass” or big-time informer. In the film, as in life, Mafiosi masquerading as policemen surprise Giuseppe at a stable and imprison him after promising him a visit with his dad. They tell his family they will execute the boy unless the informant stops talking. The moviemakers don’t flinch at his ordeal, but they don’t rub our noses in it, either. Whether they’re depicting psychological or physical torture, in close-ups or overheads, they’re equally sensitive and expressive. We feel what Giuseppe does both as a victim and, more remarkably, a romantic hero. He saves his own integrity and spirit and ultimately Luna’s life by re-reading her letter and responding to her telepathic love calls.

Sicilian Ghost Story is a spanking fresh creation, not a gussied-up docudrama. It honors Di Matteo’s story as it tells an alternative one. It conveys how acceptance of an all-powerful Mafia debases a community’s body and soul, while resistance preserves them. What makes the crime syndicate so unnerving is its peekaboo ubiquity. Except for Luna, everybody in Giuseppe’s village knows how violently it operates and has caught glimpses of its dirty work. The mob functions like an open secret. No one raises a hand to find and save the boy, not even the real police—not even after Luna fingers a kidnapper and discovers one of his workplaces. This steadily building tragedy focuses Luna’s powers (she turns her bedroom wall into an ominous epic mural). Jedlikowska’s unconventionally pretty face, round and malleable, toggles between sweetness or sullenness and toughness. It has just the right amount of opacity to keep us guessing about Luna’s next move. She takes us along a journey of mini-epiphanies. We too grow ultra-sensitive to details, like people shuttering every window in the house on a clear, calm day.

The directors have cited the great Sicilian writer-statesman Leonardo Sciascia as an inspiration, particularly his statements about a country ruled by omnipresent, unseen forces: “Sicily is all a realm of fantasy; and what can anyone do there, without imagination?” When Pauline Kael reviewed Elio Petri’s We Still Kill the Old Way(1967), based on Sciascia’s A Man’s Blessing, she observed, “It’s easy to present fantasy on the screen, but to show a man’s life in completely realistic terms as this film does and make us experience it as fantasy is difficult.” I love We Still Kill the Old Way, but I think what Grassadonia and Piazza accomplish here is even more challenging. They sinuously glide between a naturalistic version of events and scenes filled with portents, prophesies, and illusions. The settings and locations mingle organic and artificial elements, like the basement sauna in Luna’s house, built out from a cave wall. Luna’s rigid Swiss mother (Sabine Timoteo) uses it in every kind of weather to sweat out her toxins. Her poison goes deeper than that. When she expresses disgust at Giuseppe’s father and orders Luna never to see Giuseppe again, we can’t tell if that’s because his dad is connected to the Mafia or because he turned informer. She’s a tidy conformist from her pulled-back hair to the cells of her marrow.

Except for the kidnappers, there are no one-dimensional characters; by the end there’s little doubt that Luna’s mother loves her, albeit in an oppressive way. Still, Luna grows to see how ugly subservience can be as practiced by her mom and her sloppy diabetic dad even toward authorities as modest as provincial cops. This context recharges ingredients familiar from teen rebel movies. When Luna and her BFF Loredana (Corinne Musallari) color their hair electric blue, they force neighbors to notice their quest for a forgotten friend. The movie goes to the brink of excess in adolescent intensity. When a doltish classmate takes over Giuseppe’s front-row seat because, he says, the boy won’t be coming back, Loredana swiftly bashes his head on the desktop.

The directors conjure a tingling atmosphere right at the start, when Luna sees a butterfly land on Giuseppe’s fingers. (The image returns hundreds of days later, when Mafia thugs transfer him from one secret locale to another.) Is the forest a magic place, or do Luna and Giuseppe conjure magic between them? A ferret nuzzles Luna’s legs. After she coyly refuses to give the boy his love letter, she runs into a vicious dog chomping on a rabbit. (The canine reappears as the Mafia’s attack dog.) It’s as if the force of the couple’s feelings has catalyzed woodland creatures into unexpected action. With its tough mind and lyrical instincts, the movie dares to celebrate rather than debunk “magical thinking.” The pair’s love, or the intensity of their belief in love, enables them to share emotions at a distance, like the twins in The Corsican Brothers, or to project themselves into each other’s dreams, like the lovers in Peter Ibbetson. Luna’s letter seems to reconstitute itself upon each reading, as if she’s transmitting new words. It’s heartbreaking when she analogizes her life without her beau as a different kind of imprisonment.

To take just one example of this film’s evocative, lucid virtuosity: Luna sneaks into Giuseppe’s bedroom and—while holding a photo of him in his equestrian garb—imagines the kidnapping exactly as it took place. It’s as if lying on his bed and grabbing hold of his image forges a connection to his consciousness. Then Giuseppe’s grandfather enters and demands to know what she’s doing there. That postscript turns out to be a simple nightmare. She awakens in her own cramped room, with her dad instead of Giuseppe’s grandpa. Reality is porous in Sicilian Ghost Story. The town’s total denial has created an existential vacuum, and Luna and Giuseppe’s ardor rushes in to fill it.

Sicilian Ghost Story contains humor so organic that it can’t be relegated to mere “comic relief.” Loredana wryly quotes a Russian saying: “Every time there’s a moment of silence, a cop is born.” Luna responds, “Here, it’s a Mafioso that’s born.” Loredana tries to interest Luna in her boyfriend’s cousin: a tousle-haired, bespectacled wit. He wins her over with his gay, rueful vision of nature re-taking Sicily and returning it to the wild and the gods who once swarmed over the countryside. The movie leaves us with a sliver of hope. The message isn’t merely that “the children are watching us”: teens must look out for themselves.

Michael Sragow is a contributing editor to Film Comment and writes its Deep Focus column. He is a member of the National Society of Film Critics and the Los Angeles Film Critics Association, and is on the editorial board of Alta: The Journal of Alta California.