Deep Focus: Maze Runner: The Death Cure

Coming at the tail end of the Young Adult dystopia craze, the movie franchise based on James Dashner’s Maze Runner trilogy is like the runt of the litter that grows into a sinewy hound. From the first film in 2014 to the current finale, Maze Runner: The Death Cure, the director, Wes Ball, has stripped Dashner’s pop myth down to its satisfying teen-rebel essence. Its young heroes never stop asking, “What exactly are we doing here?”—then punch through to their own tough answers.

The producers have targeted this franchise squarely at middle-school kids and high school underclassmen. But, whatever your age, if you grew up at neighborhood theaters that held Saturday matinees, I bet you’ll be engaged by Ball’s affection for his cast and skill at using an apocalyptic premise to reframe setpieces from Westerns, wilderness movies, urban shoot-’em-ups, and previous sci-fi Armageddons like the original Planet of the Apes.

Starting in a grassland called “the Glade,” filled with amnesiac boys and just one girl, and bounded by a giant concrete maze with terrifying biomechanical predators known as “Grievers,” the series has gone on to encompass eerie underground bunkers and labs with suspended bodies a la Coma, zombie-like beings known as “Cranks,” urban ruins and blinding deserts (in 2015’s Maze Runner: The Scorch Trials) and now, in Death Cure, a gleaming metropolis called, with touching literalness, “The Last City.” It’s no Emerald City, just a modern urban center. (The production was based in Cape Town, South Africa.) It boasts striking vertical architecture and a wall to keep out Cranks—something, naturally, that it proves unable to do. The Last City is a poignant as well as a topical setting, because the routine traffic and commerce of a functioning Big Town are sources of wonderment to Gladers.

Ball’s straightforward, flexible technique and his ability to stage action appropriate to each locale have brought the franchise a refreshing variety. He filled The Maze Runner with surefire boys’-adventure sights, like a pack of kids using makeshift spears to battle enormous insect-like creatures. The Scorch Trials was a nonstop chase—like a Mad Max movie staged on foot.

Death Cure starts with a slam-bang train robbery before it segues into a number of cliffhangers in which the “cliffs” are urban canyons of glass and steel. It all hangs together because the director’s aim is true. When he sets up, say, a riff on Butch and Sundance’s mountainside plunge, he keeps his performers from mimicking Newman and Redford and provides them with different notes of panic and comic relief.

Seen as a whole, the trilogy could be called The Malaise Runner, because in YA easy-reader terms, it has the same onion-layered quality that Edmund Wilson found in Raymond Chandler’s novels: “It is not simply a question here of a puzzle which has been put together but of a malaise conveyed to the reader, the horror of a hidden conspiracy that is continually turning up in the most varied and unlikely forms.”

Over the course of the first two entries, we learn that a solar flare ignited a deadly global contagion called “the Flare,” infecting most of the earth’s population with a brain-wasting disease that eventually turns its victims (the Cranks) into demented cannibals. The World Catastrophe Killzone Department (WCKD, pronounced “Wicked”), led by scientist Ava Paige (Patricia Clarkson), isolated young people who appeared to be immune, and she engineered the trials they faced in the Glade as part of an attempt to test and mine an enzyme that could reverse the Flare.

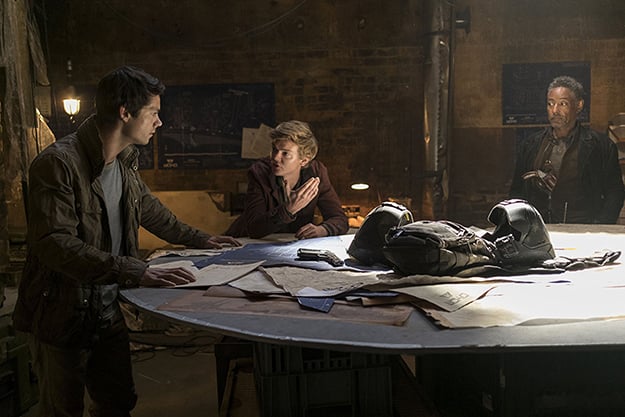

In Death Cure, Thomas (Dylan O’Brien), the leader of the Gladers, makes it his top priority to save the lead maze-runner Minho (Ki Hong Lee) from becoming WCKD’s prize lab rat. It’s a sturdy narrative peg, and the complications along the way are genuinely involving and piquant. Not all Gladers are Immunes. Some were part of a “normal” control group, which hits close to home for Thomas when his earliest counselor and best friend, Newt (Thomas Brodie-Sangster), becomes infected. The ironic catchphrase “WCKD is good” gains more traction when we see Thomas’s soul mate Teresa (Kaya Scodelario), who betrayed her fellow Gladers in the previous film, zero in at WCKD headquarters on the ingredients of a serum that can cure the Flare. Teresa switches allegiance a couple of times in this movie, and Scodelario tunes us into every one of her unspoken thoughts and fluctuations. Even better, Will Poulter shows up, full of gruff authority and charm, as Thomas’s former Glade nemesis Gally.

It’s refreshing to follow an escapist series in which an undeniably “good” protagonist like Thomas must continually re-assess his key antagonists. It helps that O’Brien, still only 26, doesn’t harden into a baby-macho mask: thought and feeling tango across his face.

If you’ve followed these movies, it’s fun to see Lee flex his muscles as the jock-ish Minho or Dexter Darden gain gung-ho confidence as the former cook and kitchen manager Frypan. Brodie-Sangster, as Newt, affectingly depicts a worried boy becoming a worried man, and Rosa Salazar brings robust warmth to Brenda, the radicalized scavenger and first-class road warrior. Among the adult performers, Giancarlo Esposito takes top acting honors as Brenda’s watchful, skeptical mentor, Jorge, while Clarkson employs her pearl-like ambiguity to troubling effect as the enigmatic, ultimately well-intentioned Paige.

In any successful franchise, later entries benefit from the reunion of actors who are comfortable in their roles and with each other. What’s marvelous about the train robbery that kicks off this last episode is the way it unites so many allies—the Gladers, Brenda and Jorge, and “Right Arm” resistance leader Vince (the great Barry Pepper)—in exhilarating feats that showcase their individual qualities of shrewdness, strength, and precision.

Ball wisely bookends that introductory sequence with a bittersweet, meditative coda that allows Thomas, and the audience, to measure his losses. This movie says that in an uncertain world, we must be loyal to our friends and honor their memories. Thomas can be proud that he tried to live up to his own renegade version of the U.S. Army Rangers’ code. He did his best to leave no Glader behind.

Michael Sragow is a contributing editor to Film Comment and writes its Deep Focus column. He is a member of the National Society of Film Critics and the Los Angeles Film Critics Association, and a programmer at the Criterion Collection.