Deep Focus: Demolition

Too often when directors use natural lighting and handheld cameras, their quest for spontaneity comes off as artificial and affected. They seem to be selling realism rather than collaborating with their actors on capturing actual behavior. Jean-Marc Vallée, who also uses those techniques, has the talent to nail down a time, place, and atmosphere definitively, whether in the trailer parks and strip malls of Dallas during the onslaught of the AIDS epidemic in Dallas Buyers Club (13) or the Pacific Crest Trail vistas and 1990s drug pads in Wild (14). Heightened naturalism is not Vallée’s only mode but it’s become his most distinctive one, especially since his seize-the-day mode of filmmaking elicits lived-in performances, like those of Matthew McConaughey and Jared Leto in Dallas Buyers Club and Reese Witherspoon in Wild. Working from Nick Hornby’s virtuoso adaptation of Cheryl Strayed’s memoir, Vallée put Wild together like an electrified mosaic, deploying soundtrack selections from the likes of Franz Schubert and Bruce Springsteen to expand the action poetically.

At age 53, Vallée hasn’t stopped growing, so I was curious to see what he’d do with Demolition, a mordant fable about a New York City financial executive, Davis Mitchell (Jake Gyllenhaal), who cracks up—or, mostly, cracks other things up—after witnessing his wife Julia (Heather Lind) being killed behind the wheel when another driver plows right into her. After watching the film, I was still convinced of Vallée’s eye and instinct for pacing and his rapport with actors, but I was less sure of his taste in scripts. No matter how much conviction and oomph Vallée and his actors bring to every line or episode, the characters are so flat, the action so whimsical, and the black humor so self-conscious that you’re apt to zone out midway through. Seeking unvarnished truth in what Henri-Cartier Bresson would call “decisive moments,” Vallée instead exposes the retro story’s flimsiness and falseness. Reminiscent of earlier parables of nonconformity in which professional men in midlife crises “drop out” or are saved by lovable “kooks,” it’s like a nightmare combination of A Thousand Clowns and Petulia. This time out, Vallée’s dynamic editing and splashy musical gambits—for example, David, post-crack-up, dancing freestyle through New York—come off as camouflage for bogus storytelling. This movie’s pleasures are marginal and fleeting. Davis may find it cathartic to rip apart his possessions and to bulldoze his glassy suburban palace, but for the audience, the film goes bust.

Afterward, a friend of mine said she sympathized with the filmmakers for attempting to portray the intense dissociation brought on by extreme grief. And that’s definitely how Vallée wants you to see the movie by the bittersweet end. What you actually witness throughout most of Demolition, though, is a man convinced that he feels no sorrow because his empty marriage was the absolute dead center of his overall hollow existence. True, in the final turn-around, Davis decides that there was love in his marriage, and that he just didn’t pay attention to it. (That’s hardly a “spoiler”—it’s included in the trailer, as part of the promise that the film won’t bum you out.) But not even Lind’s hearty presence as Julia can convince you of their affection for each other, because she’s restricted to flashbacks that aren’t even thumbnail sketches—they hardly get down to the cuticle.

Davis’s vacuum of a life extends to his lucrative job at the sleek investment-banking offices of his father-in-law, Phil (Chris Cooper). Bryan Sipe, who wrote the original script, has said that his work grew out of frustration at selling one screenplay and then writing a string of them that went nowhere. Did he research investment bankers, or merely indulge in a fantasy of the value-free one percent as the setting for a story of creative bankruptcy? This view from an upper-crust office is paralyzing in its banality; aside from Cooper’s Phil, the most persuasive office resident is Davis’s executive assistant, who looks convincingly concerned when he shows up for work right after Julia’s funeral. Gyllenhaal all-too-skillfully applies a veneer of deep-in-the-bone boredom to Davis right from the beginning, whether he’s glazing over when Julia asks him to fix their leaky refrigerator or confronting professional duties that consist (he says) of taking credit for the hard labor of his underlings. Cooper does bring his usual depth of feeling to the role of a devastated father. But since Vallée doesn’t stylize the action, yet nonetheless depicts it from Davis’s point of view, you don’t know whether Cooper’s Phil is a righteous or a delusional dude, especially when he establishes a foundation to honor Julia’s generous spirit and ability to bring out the best in people. (She worked with special-needs children.) Nothing infuriates Phil more than Davis’s dismissive attitude toward this memorial.

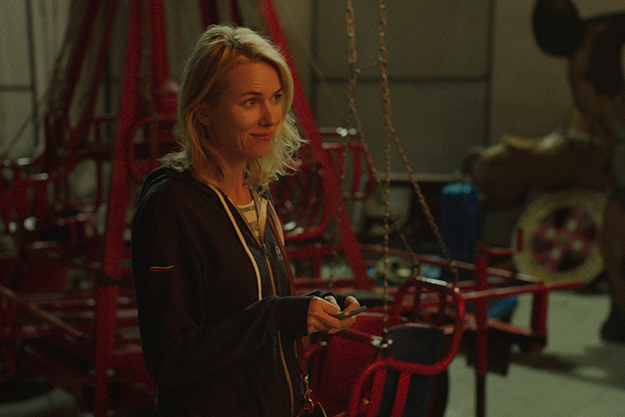

It annoys us, too. Davis isn’t merely confronting his own alienation for the first time—he’s taking it out on everyone else in obnoxiously privileged ways. At first, it is surprising and funny to see Davis immediately funnel his energies into writing frank, rambling, memoir-like complaint letters to the Champion Vending Company, whose circular-wire dispensing rack snagged his bag of Peanut M&Ms at the hospital. These letters roughly frame the action. A customer-service representative named Karen Moreno (Naomi Watts) actually reads and responds to them, emotionally. She can’t resist calling Davis one night at two in the morning to offer sympathy—you could say tea and sympathy, if you use “tea” to mean (as the Beats did) “marijuana.” She turns out to be almost as nutty as he is. The pothead single mother of a smart-mouthed adolescent son named Chris (Judah Lewis) and the abashed lover of her boss, she goes so far as to stalk Davis on his commuter train. (He gets her address from a subscription copy of Cosmopolitan that she leaves behind.) The most promising part of the movie is the bond of outsiders they form, along with Chris, who struggles with his sexual identity. Gyllenhaal and Watts both have faraway looks that fix on each other unexpectedly and wayward streaks of humor that run parallel, then intersect. They cement their not-yet-sexual friendship by building a couch fort and strolling along the beach at Coney Island. (What would movies like this do without Central Park or Coney Island?)

The key speech in the film comes when Phil advises Davis that he may have to tear his life apart before he can figure out how to put it back together. All too literally uniting the good counsel of his father-in-law and the tool set his own father gave him, Davis obtusely starts disassembling and/or junking not just the refrigerator that his wife complained about, but also (among other things) his office computer, a coffeemaker, and a bathroom stall door. He actually volunteers to work with a demolition team, and ultimately, with Chris, he batters down the front of his own deluxe, ultra-modern, glass-and metal castle in White Plains. (The real house was found and shot in Roslyn, Long Island.) When Chris asks him what he’s doing, Davis answers that he’s taking apart his marriage. That’s the kind of thing David means early on when he says, in voiceover: “For some reason, everything has become a metaphor.”

The filmmakers, like Davis, haven’t thought out this observation. A metaphor must refer to something outside itself. If everything in the film is a metaphor, then nothing is a metaphor. In Demolition, Davis’s belated realization that there was love in his marriage comes from whimsical flash cuts, like one of Julia on a merry-go-round. Demolition lacks the substance to be genuinely poetic. That’s why it turns into such an empty, vapid movie.

Michael Sragow is a contributing editor to FILM COMMENT and writes its Deep Focus column. He is a member of the National Society of Film Critics and the Los Angeles Film Critics Association. He also curates “The Moviegoer” at the Library of America website.