Close to Life

This article appeared in the July 1 edition of The Film Comment Letter, our free weekly newsletter featuring original film criticism and writing. Sign up for the Letter here.

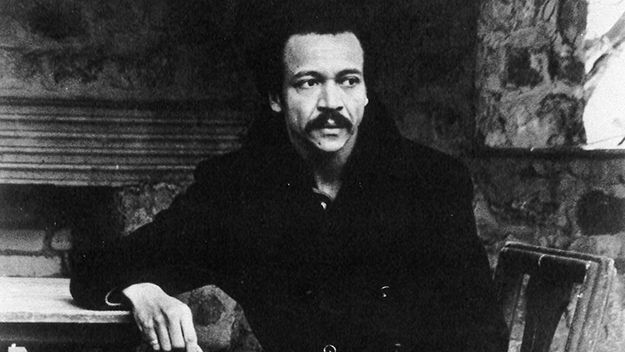

Courtesy of Artists Space

Retrospectives can be grave affairs. When the artist has already died, I find these events troubling, much like “celebrations of life.” Retrospectives are joyous because of the pleasure of experiencing the artist’s work, for the first or the fifteenth time, but they are also marked by the end of a vision. No matter how many masterpieces an artist makes there is always the chance for at least one more until suddenly, cruelly, there isn’t. Genius choked by mortality feels like robbery for the rest of us. History has been particularly unkind to Black geniuses, a category of artists who are as frequently defined by the work they have made as the promise they have been prevented from fulfilling. We haven’t yet developed a ritual for confronting that.

Artists Space’s show Till They Listen: Bill Gunn Directs America pulls together a series of performances, ephemera, and Gunn’s film work, including a copy of his rarely seen first feature Stop (1970). Gunn was a genius boxed in by racism and the difficulties of finding support for daring ideas. He started making movies only a short time after Melvin Van Peebles was rebuffed during his first attempt to find a foothold in Hollywood. (Van Peebles did, but as an elevator operator.) Had Gunn been white or a little more willing to stay on the straight and narrow, formally speaking, we would probably be able to speak more fully of a career. But he never played it safe. From the beginning he was trying to expand the formal possibilities of both cinema and theater. Traditionally, one is supposed to show they know how to play the scales first, and then a simple melody. Much later the artist might try something new. What Gunn has left us doesn’t leave me with the impression that he was even aware of such a process.

Gunn’s artistic audacity repeatedly resulted in his producers’ interference as they tried to make the work more palatable to a broad audience. Although he at times lost control of the cuts and distribution, he didn’t bow. In 1975 he returned to the theater with the drama Black Picture Show. Artists Space’s virtual reading of the piece played like an epilogue to his cinematic struggles. The play stages a confrontation between a suicidal playwright father and his sellout filmmaker son. A Black artist in Gunn’s world can either lose their soul or their mind. Black Picture Show is a mad, swirling work that I might call a psychodrama if one of the characters didn’t preempt me with the warning: “we don’t refer to Freud here.” It’s a good joke for Gunn, whose oeuvre brims with unsettled minds.

Ganja & Hess, his most fully realized work, makes the vampire a pitiable figure. We are told in voiceover that Dr. Hess Green (Duane Jones), a wealthy professor, is “an addict, not a criminal. He’s a victim.” The first time we see him suck blood, Green finds his troubled assistant (Gunn) dead by his own hands on the bathroom floor. The professor bends over and touches his lips to a pool of the man’s blood and inhales. The vampire’s bite has always been erotically charged—the archetypical location is along the sensitive skin of the neck, where one is already liable to find a blue-black bruise left by a mouth. Green’s first feeding is not that, despite the characters’ near-nakedness. It is a pathetic scene: a man doubled over, lapping up sustenance from a bathroom floor.

Gunn’s films are gripping because of his willingness to engage in heightened affect while a disquieting current runs just beneath the surface. Personal Problems is a soap opera, but most soaps are pantomimes of the workings of rich inner lives, where chaos and coincidence substitute for the dirty work of just trying to understand another person. Soaps are alluring like a car crash. A crash titillates, as queues of rubbernecking drivers can attest, but Ballard and Cronenberg aside, they do not invite you to touch. Motorists slow down, gawk, and drive on. Personal Problems, on the other hand, gets close to the bone. A group of friends are at the end of their rope in their careers, homes, and marriages, and discover that it is no end at all. One can go on dangling forever. Shot on tape and originally intended to air on television, the show was not picked up by PBS. For how rough the project is and how frequently it eschews the explosive beats of a soap opera, it still rankles. It is too disastrous in the sense that it’s too close to life.

Stop is not Gunn’s best film, but its suppression is emblematic. Gunn’s debut follows the disintegration of a marriage during a vacation, a favorite subject of European arthouse filmmakers. It is shot through with the sex and violence typical of a late ’60s freakout, but the splintering narrative and interracial swinging were too much for the producers. Warner Brothers, which had recently produced Gordon Parks’s The Living Tree, took the film away from Gunn, recut it, and then decided against releasing it altogether. Even now, as Gunn’s profile has risen, the film has not been distributed.

Viewing it at Artists Space was bittersweet. There is a thrill in seeing a film that has dropped out of circulation, but watching Stop on a small monitor affixed to the wall of the gallery was a reminder of how things might have gone differently. It was one of the first films by a Black director made for a major studio, which is the kind of achievement that typically guarantees some kind of theatrical run. Yet the easiest way to see it is as a curio inside of four white walls, where Gunn’s love of the ecstatic is curtailed by the reduced scale. It is an adventurous, uneven production, singing brightly and clearly at moments and falling to a muddled murmuration at others. But that is what one should hope for from a first feature: trial and failure, as opposed to a rote repetition of what has played safely before. One looks at the first films of Gunn’s major contemporaries—Dementia 13, Murder a la Mod, Who’s That Knocking at My Door—and sees less a perfected vision than great promise. Those directors were shepherded into bigger budgets and better support systems, and so produced era-defining work. Ganja & Hess played at the Cannes Critics’ Week the year of its premiere, in the same section as Anna Karina’s directorial debut. That edition of the festival also hosted Aguirre, the Wrath of God; History Lessons; Touki Bouki; Cries and Whispers; Day for Night; Love and Anarchy; and The Holy Mountain. In a letter to the editor at the New York Times, Gunn noted that no white critic at any of the major newspapers even mentioned the film’s existence at the festival. Lost artists are not always so by dint of the vagaries of history; they are also buried. When they disappear, so, too, does a possible lineage. The hope for a show like Till They Listen is not really that it will cement Bill Gunn in a place of honor. The hope is for what comes next.

Blair McClendon is a writer, editor, and filmmaker. He lives in New York.