Cinema ’67 Revisited: Point Blank

In my 2008 book Pictures at a Revolution, I approached the dramatic changes in movie culture in the 1960s through the development, production, and reception of each of the five nominees for 1967’s Best Picture Academy Award: Bonnie and Clyde, The Graduate, In the Heat of the Night, Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, and Doctor Dolittle. In this biweekly column, I’m revisiting 1967 from a different angle. As the masterpieces, pathbreakers, and oddities of that landmark year reach their golden anniversaries, I’ll try to offer a sense of what it might have felt like to be an avid moviegoer 50 years ago, discovering these films as they opened.

In the early 1960s, the 20-year film noir boom that began toward the end of World War II finally waned, its themes and concerns drifting away from the Hollywood mainstream. By the early 1970s, the genre was back as neo-noir, modernized (or sometimes just air-quoted) by directors like Alan J. Pakula (Klute), Robert Altman (The Long Goodbye), and Roman Polanski (Chinatown), who consciously and formally nodded to the past while going places that ’40s and ’50s film noir couldn’t. But in between, in 1967, along came John Boorman’s Point Blank. Grim, violent, elliptical, transfixingly sour and strange, it remains, 50 years later, a vital link between old and new, seeming at times like the tail end of classic noir, at others like the first sign of something fresh. It’s a hybrid of American, British, and French influences that becomes very much its own thing.

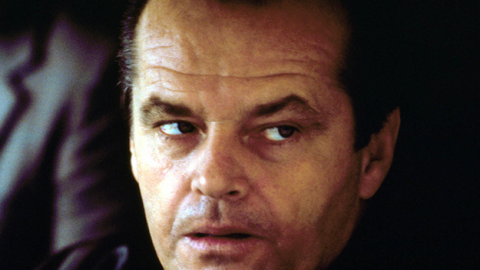

The American part was the deft and prolific mystery writer Donald E. Westlake (1933-2008), who in 1962, under the pseudonym Richard Stark, began a series of more than two dozen lean crime novels featuring a big, rugged, impassive slab of criminality known only as Parker. Westlake once said he had Jack Palance in mind, and he certainly fit his description: “His hands looked like they were molded of brown clay by a sculptor who thought big and liked veins . . . His mouth was a quick stroke, bloodless.” But Point Blank’s star, Lee Marvin, is an even more effective stand-in. And by no means the most surprising piece of casting Westlake experienced: over the decades, Parker, whose name was changed to Walker for this movie, has also been played by Mel Gibson, Jim Brown, Robert Duvall, Jason Statham, and even Anna Karina in Jean-Luc Godard’s Made in U.S.A., an uncredited and unofficial partial adaptation of the 1965 Parker novel The Jugger.

The Brit in the mix was Boorman, making his first American feature film and shooting in L.A., where the action of Point Blank takes place, with an alien’s keen eye for its modernist architecture and its massive, punitively grey concrete cityscape—skyscrapers, viaducts, tunnels, garages, overpasses—not to mention offices and homes where the dominant hues are industrial shades of avocado, orange, and khaki. This is a Los Angeles baked dry of beauty, and Boorman, shooting in color, keeps the palette impressively coherent and resolutely unpretty.

As for the Frenchness: Boorman says Renoir was an influence, but he also clearly drew on Godard and Resnais (as Arthur Penn had done a couple of years earlier with his noirish Mickey One) to create a story with a chronology that makes it feel less like a narrative than a nightmare. The plot of this pared-down 93-minute thriller comes at you in uningratiating, you-figure-it-out fragments: Walker, who is… somebody, has been shot by… somebody; a theft in which he participated appears to have ended in a betrayal by his partner; now, he’s pretty much alone in the world, out $93,000, and bent on payback (the title of Brian Helgeland’s 1999 remake).

It’s all remarkably terse and cryptic: the enemy is referred to simply as “the organization” (a group of booze-pinkened men in business suits who only have last names), and there’s no particular reason to root for or against Lee Marvin except that he’s the star of the movie and someone—Lloyd Bochner? John Vernon? Carroll O’Connor?—double-crossed him and nobody double-crosses Lee Marvin. Point Blank seems to take place in a moral netherworld, the strangeness of which is emphasized by minimal dialogue, a paucity of plot clues, and an impressionistic use of sound that seems to drop out for long stretches. When it opened, the New York Times’s Bosley Crowther—who kind of liked it in spite of himself—complained that it “develops no considerate moral sense” (mostly true) and wrote, “Holy smokes, what a . . . calculatedly sadistic film it is!” There he was off; there’s very little relish in Point Blank’s brutality, but it’s easy to understand why Crowther misread it. The film is so spare that sometimes there seems to be nothing in it but violence; violence is what anchors it and gives it meaning.

Point Blank is also deepened, and darkened, by Marvin’s presence. Two years after winning a surprise Oscar for Cat Ballou (his only career nomination), he could not have shown less interest in finding a means to return to the podium, or even in showboating. At the peak of his stardom (which was consolidated by 1966’s The Professionals and, a few months before Point Blank, by The Dirty Dozen), he is said to have won casting and script approval on Point Blank only to have told a room full of astonished studio executives that he was signing over both of those perks to his novice director. Legend has it that Marvin literally tossed the Point Blank script out of a window in the cause of paring down his own dialogue. He plays Walker as an animal, an immovable object, an incarnation of single-minded intention, most memorably in a climactic scene in which one of the film’s fatales, acted with bravura glossy toughness by Angie Dickinson, hits and hits and hits him to such little avail that he essentially knocks her to the floor simply by standing there like a 210-pound frozen steak. It’s a fantastic little setpiece of physical acting by both stars, set in a new-money L.A. mansion in which Boorman turns every modern convenience, from kitchen appliance to speaker system, into an instrument of horror. Though the collaboration between director and star was ideal—Boorman and Marvin got on so well they promptly reteamed for 1968’s Hell in the Pacific—neither man ever returned to noir, and that feels like a loss. But at least with Point Blank, they got it right.

How to see it: Point Blank is available on DVD and Blu-ray, and streams on most major services.

Mark Harris is the author of Pictures at a Revolution: Five Movies and the Birth of the New Hollywood (2008) and Five Came Back (2014).