Cannes 2022 Interview: Mia Hansen-Løve

This article appeared in the May 23, 2022, Cannes Film Festival special edition of The Film Comment Letter, our free weekly newsletter featuring original film criticism and writing. Sign up for the Letter here. Catch up on all of our coverage of the 2022 Cannes Film Festival here.

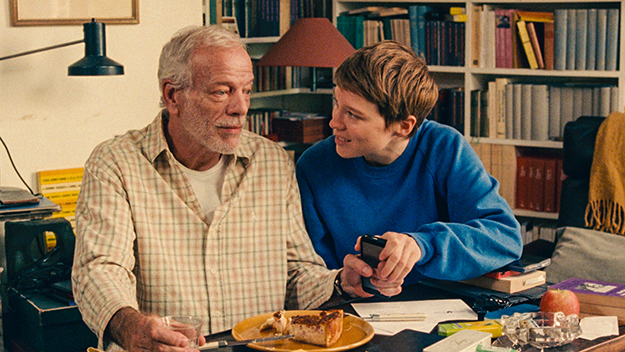

One Fine Morning (Mia Hansen-Løve, 2022)

Gravity and levity coexist in a delicate balance in all the films of Mia Hansen-Løve, but perhaps none is as effortlessly poised as One Fine Morning, the French director’s latest work of autofiction. The film follows Sandra (Léa Seydoux), a young widow and mother in Paris, as she grapples with two distinct life events: the cognitive and physical decline of her professor father, Georg (Pascal Greggory), whose fast-progressing Benson’s syndrome—a neurological condition that affects speech and vision, among other aspects—necessitates moving him into a care home; and a budding affair with a handsome cosmochemist, Clément (Melvil Poupaud), who is stuck ambivalently in a stalled marriage.

Set in a Paris that shimmers in Denis Lenoir’s warm, sunlit 35mm cinematography, One Fine Morning takes Hansen-Løve’s temporal legerdemain to its apex. To say that the film’s two main arcs—one weighed down by loss, the other buoyed by promise—are intertwined, or alternated, or simply cut together would be imprecise: the terms of narrative and filmic construction are insufficient to describe the rhythm and form of One Fine Morning, which conjures the textured density of life as we experience it.

As Sandra moves her father from home to home (providing a tour of Paris’s fraying public and private eldercare infrastructure), tries to salvage Georg’s voluminous personal library (and therefore his memory), and confronts the emotional overwhelm of a new romance, Marion Monnier’s elusive editing doesn’t so much suture scenes as collide them with each other. They cut into and finish one another, just as Sandra finishes her father’s trailing sentences, spoken and cinematic language both grappling with the shape-shifts of life. Seydoux—here at Cannes with an enviable double bill of starring roles in One Fine Morning and David Cronenberg’s Crimes of the Future—plays the sensitive, pixie-bobbed Sandra with a remarkable emotional capriciousness that imbues the entire film with a sense of possibility, both terrifying and thrilling.

Following the premiere of One Fine Morning at Cannes, I sat down with Hansen-Løve to discuss the film’s autobiographical moorings, her distinctive approach to narrative time, her interest in language, and why her movies help her “to live.”

I was struck by the title of the film—One Fine Morning in English, Un beau matin in French—because it refers within the film to a suicide, but it also represents serendipity in a positive way. It’s on one fine morning that Sandra and Clément, two long-lost friends and soon-to-be lovers, suddenly run into each other. To me, this duality seems to represent the role of chance in all your films.

I knew I had the idea of the title when I started writing, and it helped me a lot by giving me some kind of direction. But I don’t know exactly when the title came to my mind. One of the things I enjoyed about it when I found it was that I felt like I was writing some kind of diptych with L’avenir [Things to Come (2016)], which in some way could be a film about my mother. And this one would be like the reverse: even though it’s a portrait of a woman, it’s a portrait of my father as well, even if he is not the main character. We feel a lot about his past life, even though we don’t know it exactly. L’avenir had the same kind of openness and ambiguity. L’avenir [or “the future,” in English] could be seen as an ironic title because it is about this woman who is so unsure about her future, and the film brings her back to thinking there is a future for her.

I’m always happy when I find very simple titles. You often realize that the most simple titles have never been used. I also think it’s very right for the film because the film is about the cruelty of life—the fact that [Sandra] has to leave her father at the end in order to live her own life and to be happy—but there is also openness and light in it. When we say Un beau matin, we see light.

In the press notes, you say that you can’t make a film with a tragic ending. This is true of many of your films, but especially this one—it has this coexistence of grief, mortality, and the cruelties of life with a lightness that never seems forced. Since so many of your films are inspired by your life, I was wondering if that’s how you view life, or is cinema a fantasy for you, a way of imposing a happy ending on life?

Your question connects with what’s at the heart of everything for me as a director. It deals with what cinema is really about, why we make films. For me, the whole point is to find a way to do two things at the same time, and those two things can be contradictory sometimes. One thing is capturing life the way it is in the most truthful, honest way you can. Achieving lucidity, I would say. And on the other hand, I want films to help me to live. So the whole question for me is: how can I be as honest as possible—how can I be true about my experience of life—without provoking despair? If I just focus on my father’s life, the last chapter of his life, I will find no consolation. It’s so sad, and not only because of his sickness, but because after that, he got COVID-19 and died in the most horrible way you could imagine.

If you just look at one aspect of life, you find reasons to despair, but if you look at more things, you realize that maybe we just have to broaden our lens. Then you find reasons to hope, and that’s what I try to do. But while I was making this film, I didn’t feel I was betraying the truth—I just felt I was closest to the truth, because life is never about only one thing. When my father was dying of COVID-19, I was pregnant, to give you another example of how life confronts us with very opposing things. I don’t think I’m cheating or artificially creating some happy ending where there shouldn’t be one. It’s more the opposite to me. Sometimes when writers make films about difficult topics, they just press and press and press again as if there was more realism to it. But to me there’s even more artifice in pressing the same button.

How do you capture that sense of life that you’re talking about, where multiple things happen at the same time, on the level of the edit? Time moves so interestingly in your films, and particularly in One Fine Morning, where the cuts and transitions really give a sense of how different parts of life collide with each other. There’s no start and stop; you’re living multiple things simultaneously. My father’s favorite aphorism his whole life has been: “this too shall pass.”

Oh, wow, I should remember this. I’ll write it down. I like it so much. Who is it from?

It’s a famous aphorism, I’m not sure where it’s originally from.

Interpreter: It was my German mother-in-law’s favorite, too.

It’s this idea that time takes everything away, the good and the bad. That’s the sense I was getting from the film, from its rhythm.

The way that I edited this film is in continuity with my philosophy that corresponds to all my films. I’m trying to explain in my cinema that this is how life is. This is something my editor [Marion Monnier] and I pay great attention to. We always like the idea that the spectator feels that when a scene begins, it’s already underway. It’s begun before [it appears on screen], and we end the scene before it’s actually ended. You get this sense that the scene goes on without you. It gives the film a sense of movement. It reminds me of Truffaut’s quote [in Day for Night] about cinema being “like trains in the night.” This also informs the way I write the script, and the editing is a continuation of this way of writing cinema.

That’s beautiful. I also wanted to ask about language, how it works in this film. Often in your movies, people find out things about loved ones through letters or texts. In One Fine Morning, this theme is particularly powerful because the father is losing his capacity for language, and his daughter is a translator who has to complete his sentences. Where does this attention to language come from?

I guess it refers to my father and my family story. My father grew up in Vienna, so his first language was German, but he also had a Danish and French mother, and he grew up with two languages. He later became a philosophy teacher but also a translator. Before I decided to become a director, I studied German literature, and I was really into language in other ways, because of this love my father transmitted to me through having a double culture. When I write my films, I often try to have the characters do a job that I could have done. I want to be interested in what they’re doing.

Did you want to be a cosmochemist?

[Laughs] No, although I find it quite interesting. If I hadn’t become a director, I could have wanted to become a translator. I find that job very beautiful, this idea of passing through somebody else’s thoughts. It’s a relationship to language and another culture that my father transmitted to me, and somehow is transmitted to the film.

It’s really moving to see Pascal Greggory in the role of the father. He’s someone many of us are familiar with from French cinema, particularly Éric Rohmer’s films, where he talks a lot. He’s a beautiful talker, so it’s very affecting to see him lose language in your film.

It’s so nice to hear you’re aware of that. It’s not the main reason I chose him—the main reason is that I knew how great he would be in that part—but I enjoy the idea that he embodies the idea of language, of a style of language too. Of course, it’s an additional value for spectators who have seen him in the Rohmer films and can recall them. But even people who haven’t seen them get that sense of someone who’s so at ease in language, so elegant with it. It was very important to me that we feel the tragedy of the loss of language for that character. It’s tragic for everybody, but maybe it’s worse for someone who’s been so devoted to the clarity of language, as a philosophy teacher, as a translator, and as someone who loved books—they were the heart of his life. When we hear his notes in the film, he says that what he liked most about life was reading.

Also I felt somehow… not guilty but something like regret when I started making this film, about the fact that I was making a portrait of my father when he was sick and that people would not have the chance to know the man he was before. The awful thing about this disease is that it takes up all the space. It’s not that you forget who the person was. it destroys and sullies the memory of the person, of how you remember them. In this portrait of my father during his illness, I was hoping I would rediscover or return to who he was before. I think Pascal Greggory embodies that.

In the film, Sandra tries to hold on to that memory of her father through his books. The close-ups of those books are some of my favorite shots in the film. Are they your father’s books?

Yes.

And did you actually give them away to his students, like Sandra does in the film, or do you still have them?

I used the film as an opportunity to collect the last boxes of books that we had in his and some of his friends’ basements. I was still in the process of bringing back the books and recreating my father’s library. Thanks to the film, I had the set designer go get the boxes and use them in the film, and then we sent them to the place where I recreated my father’s library. I find that quite beautiful, how cinema and life sometimes work together.

That’s a good way to describe your films.

Thanks!

Interpreter: “This too shall pass” is a Persian saying, originally.

Ah! Thank you for sharing that, it’ll stay in my mind for a long time.

Thanks to Robert Gray for his French-English interpreting.