Camerimage Interview: Denis Lenoir

Denis Lenoir’s collaborations with Olivier Assayas form one of the great director-cinematographer partnerships of modern movies, from the director’s first feature Disorder (1986) to Demonlover (2002). Their partnership, which hit its apogee in Cold Water (1994) and Late August, Early September (1998), relies on Lenoir’s graceful and flexible approach, which has seeped into the loose style of many contemporary films. His gorgeous recent features with Mia Hansen-Løve, Eden (2014) and Things to Come (2016), show his lyrical touch still flourishing. Lenoir travels between Europe and Hollywood, and recently shot a portion of Jennifer Fox’s Sundance-premiered The Tale.

Film Comment’s interview took place in a music-rehearsal room at the Camerimage Film Festival in Bydgoszcz, Poland. Lenoir has strong opinions about film and digital, including an intriguing concern about the effect of digital photography on actors with blue eyes.

Things to Come

Your job has to do with how technology can help get to an artistic goal. Because of shooting digitally, is that now easier or is it more complicated? Or the same?

I have a lecture ready on that topic! I think that digital makes it much easier in many ways. Before World War II, the cinematographer was some kind of magician on set. He was generally hiding, from his own crew, the filter he was putting on the lens for the close-up of the actress—he’d remove it and take it away, like it was a secret. He was making tests, developing tests, looking at the negative. [In the early 70s] I learned at film school about lighting shadows, which means some light would [gestures around the music room] bring a shadow of this piano there and then you would bring some light to light the shadow itself. Ultimately the film set was extremely bright, there was light everywhere—it was like a carpet of light. And then the next day at the dailies, you would see chiaroscuro with deep shadows and contrast, which the eye couldn’t see [on the set]. On a film in 1973, Les Autres by Hugo Santiago [on which Lenoir was second assistant camera], at the end of every take, everyone used to turn to the operator, including the director, meaning, “How was it?” And the operator would say, “Very good for me,” and the director would ask for another take for the actors or move on. But the only person able to judge the take as technically good, also in terms of pace, how people enter the frame and go out, was the operator. And if he was saying, “I think we need another take,” no one would argue, we’d do another take.

Then in the early ’70s, Jerry Lewis, who as you know was a big directing star in France, invented the video playback. We didn’t have it in the ’70s, but we had it later. And when we had video playback, the importance of what the operator was saying about what has just been shot disappeared. At the same time the lenses became faster, the film became faster. So now the lighting on set in the room was slowly going to the same level as what you need to look with your naked eye. Now we are well past that—the camera can see way more and brighter in some ways than the eye. At some point what you had on the video [monitor], in terms of lighting and contrast, was not at all what you would get in film the next day, and there was still the director asking the DP, “Will it be like that?” and the DP would say “No, don’t worry, it will be way darker or brighter.” All this has disappeared. Now what you see on a good monitor is what you’re filming. I remember filming with Mia-Hansen Løve some love scene with literally two practical bulbs, and she was saying that it was too bright. It was difficult for me to explain that in the time of neg we would expose a little more and then print down to have a good solid negative from which you could do more things.

Any other specific issues with digital?

One problem I have now—and this is something I think is totally ignored by my colleagues, and eventually also by me—we film with so little light that blue eyed actors now have a big pupil, which is actually stealing the blue from them, or some of the blue. Now that I have told you that, you will start noticing it. Of course, it is somewhat easy to correct, by putting more light on the actor. But at the same time, do you have the time to do that? Do you have the will to do that, to stop the pace of filming? Most of the time, no.

Since the transition happened, have you found it easy to change back to film?

I shot Things to Come on film two years ago. Mia Hansen-Løve wanted to shoot on film. And I went dragging my feet because I didn’t want to have to light for exposure, because the great thing about filming digital is that you light for artistic reasons—I don’t like that word, it’s more a craft than an art. Ultimately I shot film the way we would have shot digital, with very little light.

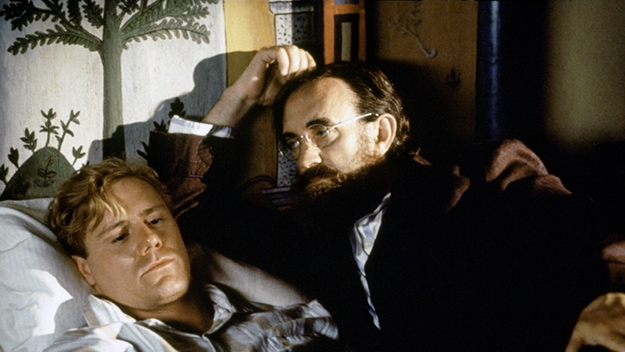

Carrington

Can you give examples of how you work out particular shots in collaboration with a director, especially when you both have ideas for the shot?

There is a shot I am happy to talk about in a movie I love, which is Carrington [1995]. There is a crane shot at night: you are outside of a country house, and you go through one window, you see a couple going to bed, then the camera moves along the house to another window, another couple, then you go down and you see other things, then it pulls back to the garden and Carrington is alone looking at the house. And this shot tells the whole story of the movie and that point in the life of Carrington, which is that her ex-husband is with another woman, she is with a lover and she’s alone. And it is a beautifully designed shot, which is obviously fun to shoot and pleasant to look at, but which has a lot of meaning and depth and tells the whole story.

Carrington was Christopher Hampton’s first movie [as director]. He’s not really a visual man, in the sense that many times I was at my camera and he would say “Denis, pan a little to the right.” And I would obey, but at the same time I would say, “This guy probably never took a picture in his life, he has no idea of framing at all, why is he thinking that he knows better than me,” grumbling like that. But he had this shot designed in his mind before hiring me, probably while writing the script. This is an example I use with directors often; even if you think you are not visual, I’m sure there are a few strong images you have for this project already. Please let me know, give them to me because from there we will be able to elaborate together and create the missing pieces in some way.

A gentleman who picked me up in an office earlier today to come with me here was telling me about a shot in a movie I also love called Eden by Mia Hansen-Løve again. The shot is at the end of the movie, with the hero in a club in Paris. We all know it is the end of the story, that he has fucked his life, that he is starting again. And you pan the room, and you land on the little stage where the young woman DJ with a Mac is playing this Daft Punk song and she’s 15 years younger and she’s making him totally obsolete, in some way. And this is a shot totally designed by Mia. I remember I was moved while filming it, but also it was not me—Mia was really executing it, which is the case most of the time. My friend Caroline Champetier was here [at Camerimage], we hadn’t seen each other in a while because I live in Los Angeles, and she was telling me about Things to Come and how graceful my filming was, and I was saying thank you, very sweet of you, and I appreciate it but at the same time the grace is from Mia Hansen-Løve. And it’s not because I am super modest or humble—no I am not, my ego is a big as yours.

Entre ses mains

But are there times when the director is setting up a scene, and you bring the idea of moving the camera?

I developed with Assayas—I shot his first five movies, and his first movie was my second, so in some way we grew up together. Then, life happens, and I work with other directors, which made me grow. A DP learns something from a director and then brings it to another director. It is very important, and it creates a reason for a director to change DPs every once in a while because he will learn new tricks. I shot a pilot in New Orleans recently for American TV with Houda Benyamina, the director of Divines. She doesn’t have so much experience, but she is extremely smart, extremely hard-working, full of will, an iron lady—but she told me how much she was learning from me, and I’m quoting that not because she was learning from me, but because she was learning from me having myself learned from other directors.

Many directors ask to do a shot list ahead of time, and I try not to do it. It makes sense to eventually isolate a few moments, like in the case of the Hampton crane shot. But otherwise, trying to fill in the blanks in a room, with no actors and not in the proper location, makes absolutely no sense to me and I just find it so boring. Also I am somehow inhibited by my belief that you can a film any scene a thousand different ways. So I learned with Olivier, or we learned together or we discovered together, to do complementary singles—mostly handheld but it doesn’t have to be. You start with a dialogue scene and the first important thing to share with a young director is to please have your actors moving around, it makes it more fun to film and all. And then you start with a single on one, eventually it becomes a two-shot, and then you go with the one actor and finish the scene. Then you start with the other one, you go to the two-shot. And the idea is that you keep the eyeline over time—if possible a tight eyeline, because I’m a big fan of a tight eyeline—and then at any point the editor or director can cut from one to the other. But I’m very good at first explaining this method and then executing it.

I shot [2005] with Anne Fontaine, and she did something that was, for me, a bit strange at the time. We were filming in the North of France, Lille and some other town. Two local young actors had learned the script. And we would go—Anne, the two actors, the continuity person, and myself—on location and then Anne would say to the young actors, “Okay, do the scene.” Local young actors, kids, 18 to 20, not very experienced. And the kids would try to move around and say the lines. And then Anne, little by little, would change them, suggesting they do this or that. And then at the some point, Anne would be happy with the blocking. And then she would turn to me and say, “Oh, how do you film it now?” And I would say “Oh, I don’t know, I could do this, that.” And she would say, “Yes, why?” “Yeah, I’m not sure, maybe because of this or that.” So by going and correcting and changing a little, she finally would go to a stage where she would be happy with the way it would be filmed, and then she would go with the continuity person and say, “Okay, write it down.” We were doing the shot list like that. At the time, I was thinking, “She’s a joke, she’s an impostor, I’m directing for her,” and all that. Ultimately—and I’m not saying this to be diplomatic—at the end of the movie I was convinced she was as much a director this way than somebody who had the shot list done in a bedroom the night before. A different method, but totally owning her movie.

Monsieur Hire

This style that you were talking about that you developed with Assayas, you see it a lot now. People have been influenced by it. Do you feel that? I’m thinking of David O. Russell’s films, and just moving in and out of a two-shot and being able to match different takes.

Probably. Yeah, it makes sense. At the same time, things are discovered at the same time, including science and technology.

Quite different from the Assayas films is Monsieur Hire [1989] directed by Patrice Leconte, which has a very formal Hitchcockian style. I wondered if you could speak to the creation of the sequences where Michel Blanc is looking at Sandrine Bonnaire’s apartment across the way. What you see in his room is very cold and blue and monochrome, and then past him her space is very warm and red.

It was the beginning of my career, really. Not my first movie, but the first two or three years of the features I was doing. My first few films, from just a few years before, were just terrible—not Monsieur Hire, which I’m happy with. The second film I shot was Disorder [1986] by Assayas, number three was Tandem [1987] by Leconte—many of these films were with desaturated colors, skip bleach, things like that. [Roger] Deakins had shot 1984 like that before. And in France we had a Tavernier movie about this painter, also skip bleach, beautiful lighting.

A Sunday in the Country [1984]?

Yes. And I shoot two or films with these kinds of things. And Monsieur Hire was like that. But because I had come out of some skip bleach movies like Disorder, first we did something with the makeup, not with Monsieur Hire himself because we wanted him very white, but with the others. They were made up with more red so when we would desaturate the colors there would still be colors, because otherwise the skin turns gray. Because I was a little bored with my own monochromatic lighting, I wanted to add some light in the filming, because I knew it would be removed somewhat in the lab. Something happened to Connie Hall like that on Tequila Sunrise [1988]. He shot that with a lot of colors thinking it would be skip bleach, and the technicians changed their mind or refused to do it, so that film is filled with colors. So on Monsieur Hire there were some strong color choices, color gels and all, to give—I’m not sure if it was some psychological meaning, even though the blue-green was on this side and the warmth on the other.

Cold Water

The scene in Cold Water [1994] directed by Assayas at the party with the bonfire looks like it was chaos to shoot. But is something like that really complicated or chaotic, or is it controlled? How do you get that sense of explosion?

Literally around the fire it’s more like news work, filming what you can because there is no script, there is no dialogue to follow so it is more freewheeling. But the rest [of the sequence] in this house at this party which lasts forever is all choreographed and designed, including when they smoke the joint, going from a crowd to a kid to some other kid. All this was choreographed by Olivier, but also adjusted by me, because of speed or because we missed this guy or whatever.

Will you be working with Oliver Assayas again?

We are somewhat close—when I go to France, I generally see him. But I don’t think we will work together again. He’s very happy with Yorick Le Saux. I passed two times on his films, which is a capital sin.

You don’t do that?

You don’t do that. This is something we should be taught at film school.

Robert Horton is the film critic of the Seattle Weekly.