Art/Form: Memories of Utopia: Jean-Luc Godard’s “Collages de France” Models

Eighteen maquettes, restorations of ones fabricated by Jean-Luc Godard as part of a proposal for an exhibition at Paris’s Pompidou Center, are on display at the Miguel Abreu Gallery under the title Memories of Utopia: Jean-Luc Godard’s “Collages de France” Models. For anyone interested in Godard’s films, the exhibition is essential.

In 2006, an installation by Jean-Luc Godard was mounted in Paris at the Pompidou Center in conjunction with a then complete retrospective of films and videos, many in new prints and digital transfers. The installation, titled Voyage(s) en utopie, Jean-Luc Godard, 1946-2006: à la recherche d’un théorème perdu, was remarkable for what it achieved and what it did not. Godard had first proposed an installation titled Collage(s) de France, archéologie du cinéma, d’après JLG, which the museum rejected as being too large and expensive to mount. Godard compromised, but he made no secret of his dissatisfaction, making his quarrel evident in a poster that was part of group of images just outside the entrance to the first of the three rooms comprising Voyage(s) en utopie.

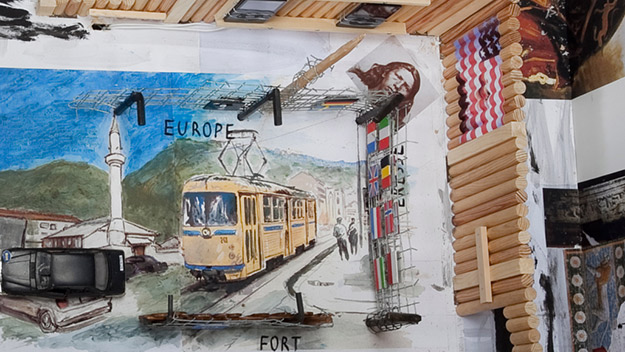

Having once proclaimed that in narrative there was always a beginning, middle, and end, but not necessarily in that order, Godard labeled the three rooms of the installation “Minus Two,” “Three,” and “One.” Although visitors entered at “Minus Two,” the path through the installation was not predetermined. What distinguished Voyage(s) en utopie from Godard’s films was that one had to negotiate the space of the installation and organize the time one spent there on one’s own. Writing about the installation for Film Comment (July/August 2006), I noted that my immediate response was that the space seemed visually chaotic and the cacophony of sound from the speakers of several dozen monitors added to the assault. “The effect is of a circus gone out of control or, because of the many wire and wooden fences, an internment camp for art and ideas. The sheer number of ‘things’—most of them familiar Godard fetishes—is overwhelming. There are monitors ranging in size from two to 60 inches running clips from films by Godard’s favorite directors (Bresson, Renoir, Welles, Chaplin); by Godard himself, including half a dozen made specifically for this installation; and by some loathed directors as well. There are wires attached everywhere, big ladders, small ladders, a bag of potting soil that’s part of a video garden (shades of Nam June Paik), generic home furnishing including the aforementioned bed, and books nailed to tables, fences, and floor. Toy electric freight trains run on tracks that tunnel through the wall between room Minus Two and room Three—how can you see a freight train and not remember the Holocaust, especially with a sentence from Bergson’s Matter and Memory, one of the nailed books, spilling onto the nearby floor?” It was as if Godard had emptied his consciousness into the space, creating a three-dimensional version of his film masterwork, Histoire(s) du cinéma—one which viewers could edit at will, creating as they moved through the rooms and then in memory, their own “imaginary museum.”

André Malraux’s text “The Imaginary Museum” has been a major influence on Godard’s films. Malraux asserts that photographic reproduction allows us to make connections among works of art which we would never be able to see in their original form, and that, together, these works, whether we know them as originals or reproductions, comprise our imaginary museum. With Voyage(s) en utopie, Godard brought his imaginary museum into the museum proper, albeit in a version considerably reduced from his original proposal. That proposal, however, made its way into the Pompidou show in the form of nine maquettes, which Godard had fabricated by hand, miniatures of the nine rooms Godard originally proposed, all of them packed with objects, original artworks, reproductions, tiny screens exhibiting films, each maquette a puzzle of form and meaning. The Pompidou exhibition was therefore two shows: Collage(s) de France inside Voyage(s) en utopie.

In the exhibition at the Miguel Abreu Gallery, there are 18 maquettes. The smaller set of nine are restored from the originals. The other nine are slight enlargements of the originals, refabricated in collaboration with the set designer Jacques Gabel. Some of the enlargements have additions which, I presume, were specified by Godard. That there is a second set makes the issue of origins and originality that much more paradoxical and reinforces the connection to Malraux. (The gallery has a detailed set of notes on each maquette which you can request at the front desk.) There is something of a mystery around how the maquettes got to Abreu, who exactly restored them, and why each of them is being exhibited in two sizes. I was told that Godard did not participate in the exhibition itself; when the museum shipped the contents of the 2006 exhibit back to him in Switzerland, he refused to pay the customs charges for any of it, and the stuff would have wound up in dumpsters had it not been saved by a private collector, who was involved in the restoration. In addition to the maquettes, the exhibition here includes Godard’s drawings (he can really draw), xeroxes of posters “altered” by Godard, and excerpts from Histoire(s) du cinéma and several other collage films by Godard and Anne-Marie Miéville.

Image by Nicolas Rapold

The maquettes are displayed on individual tables, scattered widely through the gallery. One can move around each table, looking down at the tiny “rooms” from above or peer in through their side windows or, in a few instances, glass walls. It would be easy to spend as much time in the gallery as it takes to view the four-hour-plus Histoire(s) du cinéma. Unlike the Pompidou show, the Abreu exhibit is noticeably hushed except for the sound tracks of Histoire(s) du cinéma and the other collage films, which bleed from the projection room over the entire gallery, making palpable the connection between the films and the maquettes, both archaeological investigations, as Godard described them, of cinema as the history of art.

Memories of Utopia: Jean-Luc Godard’s “Collages de France” Models is on display at Miguel Abreu Gallery, 88 Eldridge Street, through March 11.

Amy Taubin is a contributing editor to Film Comment and Artforum.