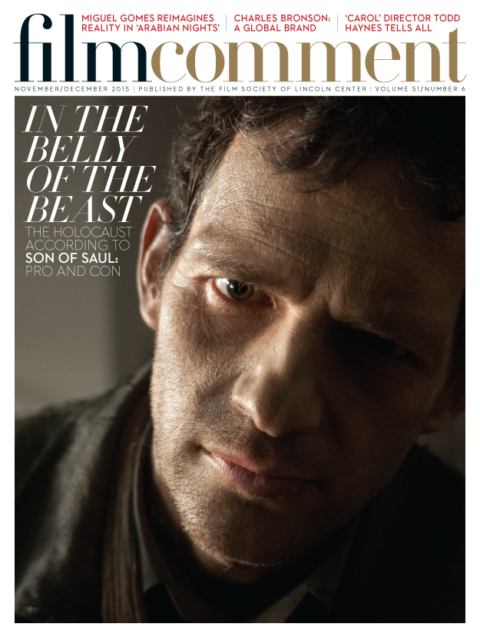

By Olaf Möller in the November-December 2015 Issue

History Men

Venice’s old guard kept the International Art-House whippersnappers at bay

Alberto Barbera must like being the director of the Venice International Film Festival, and would surely be delighted if his contract were to be renewed for another four years. And so in contrast to last year, the 2015 lineup worked hard to avoid antagonizing any one. No cinephile shenanigans this time, and no flirtation with down-and-dirty genre films! Respectable, responsible crowd-pleasers were warmly welcomed.

From the November-December 2015 Issue

Also in this issue

Movies that were more intellectually demanding and aesthetically advanced if not experimental was kept to a minimum, and usually left to the old masters—most of the youngsters delivered work within the tight constraints of “Inter-Art-House” (International Art House) orthodoxy. Little in the way of the new or unconventional can be expected from most of those who have traveled the creative-labs-and-campuses circuit, and once a few of those logos turn up in the opening credits, you might as well head for the exit. No surprise then that none of the best films by new directors bore any of those increasingly common insignias.

The 72nd edition of the festival was judged timid and weak, but in fact there were as many extraordinary films on show as last year, just in different, less extravagant directorial registers. The programmers try too hard and lack a certain nonchalance in their approach, but they at least have their hearts in the right places, and as an idealistic film-cultural statement, the competition displayed a commendably wide range of aesthetics and offered films from truly all corners of the globe. But too many selections proved mediocre and so the program remained an assortment of fragments that never came together. Barbera et al. exemplify the new breed—art administrators, politicians of audiovisual pleasure, in a word: curators. As Aleksandr Sokurov wryly notes in Francofonia, the interests of curators can be readily aligned with the requirements of dictatorships.

The Clan

This year’s awards would certainly have pleased most of the totalitarians of recent history—that’s how conservative-verging-on-reactionary they seemed overall, even if half of the winners had their merits. Lorenzo Vigas’s Golden Lion winner From Afar was not one of the better half: overwritten, and with self-consciously artsy visuals, it was just one more helping of alienation blues about a tormented relationship, this time a gay one. Even those who had good things to say about this run-of-the-mill Inter-Art-House fraud were puzzled by the jury’s decision. Things didn’t improve much when the Best Director Silver Lion went to Pablo Trapero for his efficient true-crime drama The Clan, about a Buenos Aires family in the Eighties that made its living from kidnapping. As a genre film for people who hate genre cinema, it’s totally fine and its story is certainly fascinating: one member of the family was an international rugby star, adding a sensational edge to a grim tale of murder galore. So, yes, the two main awards were given to the two competition films from Latin America—by a jury with Alfonso Cuarón as president. Looking at the rest of the awards you do get the impression that Cuarón skillfully played a group totally at odds with one another—that’s what happens when jury members can’t find any common ground.

And so it continued: Charlie Kaufman and Duke Johnson picked up the Special Orizzonti Jury Prize for Anomalisa, a cute piece of Capra corn with stop-motion animation that was universally liked—unsurprisingly, given its liberal politics, good humor, and well-measured moments of depression, darkness, and despair. It would have been a wiser choice for top honors, as it’s a film for anyone who ever felt at odds with the world—whether art-house patron or multiplex rat—and that’s something that gets rarer by the year, especially as decently done as it is here.

Cary Fukunaga attempted the same thing with his Uzodinma Iweala adaptation, Beasts of No Nation, but failed miserably—the film is one vile mess. Over the first hour, the film develops some serious war-movie drive, with the adult commander of a child soldier corps emerging as a sinister antihero. But to remind us that he’s actually a psychopath, the film’s child protagonist is forced to give his leader a blow job (off screen), neatly transforming the commander into a pedophile. The scene comes straight from the novel but plays as if something beyond the pale and unrelated to warfare had to be introduced to get things back on the morally correct track. And this is only the most blatant example of the film’s perniciousness. Still, it won Abraham Attah the Best Young Actor Award.

Anomalisa

The only film to hit the jackpot twice, and deservedly so, was Christian Vincent’s Courted, which won Best Screenplay for its auteur and Best Actor for its star, Fabrice Luchini. Screened toward the end of the festival’s first half after a seemingly endless succession of Blue Chip bollocks and Nouveau Cinéma de Papa horrors, Courted felt like a breath of fresh air with its honest, intelligent craftsmanship. Whether it still looks as good sans the bad company of Tom Hooper’s The Danish Girl, Luca Guadagnino’s A Bigger Splash, or Xavier Giannoli’s Marguerite remains to be seen—but this swanky fusion of courtroom drama and boulevard comedy is the kind of middle-ground cinema few filmmakers know how to make anymore.

Let’s mention only in passing the Best Actress prize for Valeria Golino’s performance in Giuseppe Mario Gaudino’s small gem, For Your Love, and the Special Jury Prize for Emin Alper’s Frenzy. Too bad that Oliver Hermanus’s The Endless River, a curious rural murder drama with unexpected mystery and Western touches, went home empty-handed. While not that outstanding, with its plot twists and directorial turns it was certainly more well-rounded and achieved than Alper’s politically interesting yet pedantic sophomore effort, and an award would have been an encouraging nod toward South African film culture, which always seems on the cusp of something extraordinary.

The Orizzonti jury chose jake Mahaffy’s disturbing study of one believer’s desperate need for a sign from God, Free in Deed, for the Best Film Award, which was an agreeable compromise decision. Gabriel Mascaro’s rather tame Neon Bull, a darling of many, was awarded the Special Orizzonti Jury Prize, rather redundantly since it was merely another variety of realist minimalism, artistic ground already covered by Mahaffy’s film. Something more brash might have been preferable, e.g., Anita Rocha da Silveira’s Kill Me Please, a playful but disturbing mix of echt Brazilian teen horror and coming-of-age movie, or Tamil maverick Vetri Maaran’s Interrogation, a bracing dose of old-school political cinema that tackles head-on the kind of police brutality and corruption that “closes” roughly 30 percent of all cases in India.

The Childhood of a Leader

Both the Best Director Orizzonti Award and the Lion of the Future Award for First Film went to Brady Corbet for The Childhood of a Leader, which took history by the horns in a way otherwise dared only by the old masters. A loose adaptation of an early Jean-Paul Sartre short story and John Fowles’s The Magus with some of Hannah Arendt’s The Origins of Totalitarianism stirred in, it’s intriguingly set in a mansion in the French hinterland shortly after the end of World War I and centers on the troubled, neglected son of a member of the U.S. delegation working on the Versailles Treaty. His father is rarely home, his mother is distracted, and his nanny is a young beauty who doesn’t yet know what to do with her attractiveness. Eventually the boy’s sense of rejection and superfluousness leads to a series of tantrums, each more violent than the previous. Finally, in the film’s coda, now adult, he is revealed as a totalitarian dictator making a public appearance. It may be far-fetched, but so are most theories about the psychological makeup and conditioning that produced such individuals. Corbet’s film suggests that the boy is the product of the charged atmosphere of the postwar era, that he is in effect the child of the re-ordering of Europe. And if it sounds a tad overwrought, as a cinematic experience it makes total sense due to Corbet’s feel for space and texture, rhythm and light, telling or suggestive details, and dialogue that’s often more about creating a mood than delivering information. The Childhood of a Leader brings to mind André Delvaux’s melancholic 1971 film Rendez-vous à Bray, but it’s smarter and has a furious, savage temperament.

Although Aleksandr Sokurov has always enjoyed changing tack from project to project, Francofonia still comes as a surprise after Faust. Insofar as it’s a fact-based fantasy about a museum, in this case the Louvre, it’s a companion piece to Russian Ark. The narrative center is occupied by Sokurov himself, whose nocturnal ruminations about the connections between war and peace, art collections and conquest, Western and Eastern Europe fill the soundtrack and provide plenty of food for thought. At the heart of the film is the unlikely, quietly ironic friendship that develops during the occupation of France between Jacques Jaujard, the Louvre’s director, and German officer and art historian Count Wolff-Metternich zur Gracht—a relationship that comes to mirror Franco-German relations from the postwar era right up to the present. Francofonia is full of such timely historical ironies: for instance, as a result of Napoleon’s plundering during his occupation of the region that would become Syria and Iraq, art treasures of the sort ISIS is now bent on destroying are housed safe and sound in the Louvre.

But Sokurov goes further to contemplate 20th-century Russia and its Soviet past, St. Petersburg’s Hermitage (another gigantic museum filled with the world’s art heritage), the siege of Leningrad, the death of millions, the devastation of a world-class city whose fate didn’t seem to matter as long as Paris remained intact—just as the Slavic people seemed destined to be second-class Europeans, born to suffer and find strength and belief in that suffering. At least that’s how Sokurov sees it, and if his philosophizing rambles at times, he still nails many unpleasant truths. Like others from the conservative, if not at times plainly reactionary, school of high modernism (Hans-Jürgen Syberberg, Manoel de Oliveira), Sokurov has an alert mind and can be a commendably cantankerous polemicist whose opinions and convictions merit close scrutiny. For all its playfulness, the mood of Francofonia is unremittingly bleak, but it’s not without hope—otherwise Sokurov would have probably given it a title like Elegy for Europe.

Rabin, the Last Day

Also cautiously hopeful is Amos Gitai’s Rabin, the Last Day, a political thriller in a modernist key that some saw as a hybrid form along the same lines as Francofonia. Not so: it’s just a fine example of filmmaking inspired by real events that happens to use some documentary footage. Gitai details the investigation into the blunders that led to the assassination of Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin on the evening of November 4, 1995 and situates it within the context of Rabin’s attempts at signing a peace treaty with the Palestinians. Such a treaty would have meant giving up land that was and continues to be occupied by the so-called settlers, some of whom belong to the fundamentalist-orthodox end of the spectrum of Israeli society that is armed to the teeth and ready for violence. For those who know anything about the killing, Gitai offers little that’s new in terms of information, but that’s not the point. Timeliness is what counts: Israel’s political impasse can be traced back to the paranoia that killed Rabin and to the language of communalist hatred that created his killer’s state of mind. And there’s also an economic dimension: fertile land equals capital, and if Israel made peace with the Palestinians, the fundamentalist-orthodox right-wingers would stand to lose a lot of money.

Gitai was probably the great loser at Venice this year. For once, he had the critical consensus behind him, and most people were happy at the prospect of his winning the Golden Lion. That won’t happen again soon.

As usual, a final round of deep bows. First, for two outstanding debuts in distinct realist idioms, Liu Shumin’s The Family and Vahid Jalilvand’s Wednesday, May 9. The former is a variation on Ozu’s Tokyo Story that starts out as a paint-by-numbers exercise in the quietism du jour, develops in ever more eerie, ellipsis-riddled, and interruption-prone ways, and finishes in a totally horrifying fashion that comes out of nowhere and yet makes sense. Jalilvand’s film, a meditation on grace anchored in a very simple story about a man trying to rid himself of guilt by offering to do good, is the epitome of simplicity and clarity and made with a humility that borders on the self-effacing.

Next, for two extraordinary examples of Direct Cinema at its most classical: Frederick Wiseman’s In Jackson Heights and Gianluca and Massimiliano De Serio’s Memories of the River. America’s past master of this particular idiom presents a particularly liberal New York neighborhood as an example for how an enlightened society should function. Italy’s most interesting younger filmmakers, for their part, create an epic of disappearance by filming the destruction of a Turin shantytown. Shooting the bureaucratic pandemonium as the inhabitants are divided into those granted housing permits and those who aren’t, the De Serio twins capture an actuality that brings shame to all Italians.

The Men of This City, I Do Not Know Them

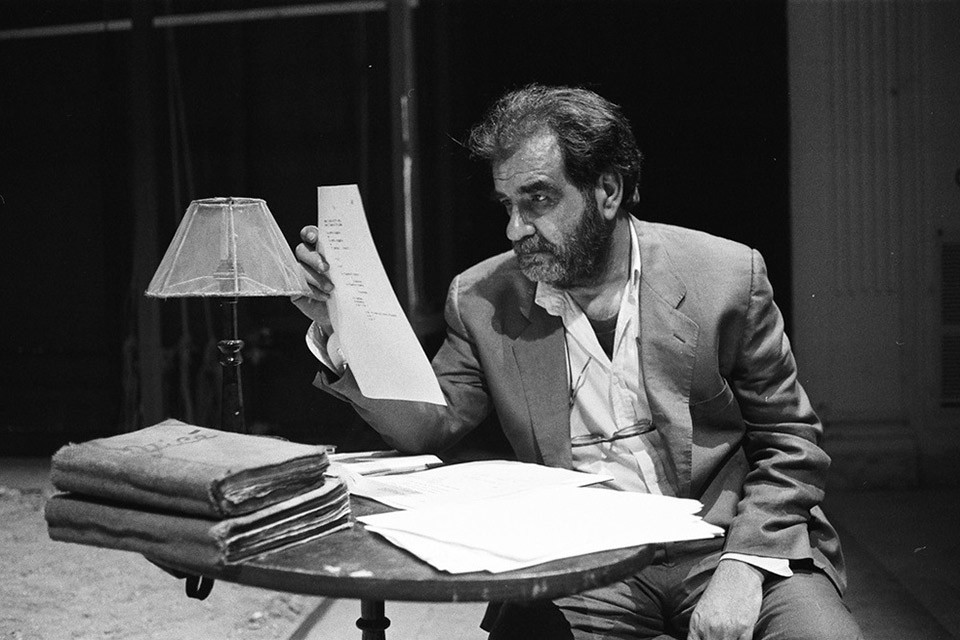

Third, for a trio of loving portrait films: Tsai Ming-liang’s Afternoon, Noah Baumbach and Jake Paltrow’s De Palma, and Franco Maresco’s The Men of This City, I Do Not Know Them. The first is a lovely double self-portrait of Tsai and his muse Lee Kang-sheng discussing their life together while the sun shines down on the green valley their home overlooks; in the next, De Palma shows his prowess as a monologist, and while little that’s surprising gets said, it’s a pleasure to be guided by one of New Hollywood’s more original minds through his career, with glimpses of painful aspects of his private life. The last of the three is an obituary for Franco Scaldati, an unheralded genius of 20th-century Italian theater, full of caustic humor and at times almost unbridled rage.

Fourth for Sergei Loznitsa’s The Event, for which a capsule description might read: “The 1991 attempted coup d’état in Russia presented in the style of last year’s Maidan by way of Loznitsa’s 2005 film Blockade.” In other words, The Event shows a nation on the move, on the brink of a historical precipice, using only found footage and arranged in a manner that stresses the artificial nature of the process, and its cool and ghostly beauty, with a glimpse of a younger Putin already in the thick of the action.

And one final bow to the late Claudio Caligari’s Don’t Be Bad, this genuine outlaw auteur’s third feature. Like his Toxic Love (83) and The Scent of the Night (98), Don’t Be Bad mixes realism and genre as it examines criminal lives at their most mundane with a vigor and nerve that calls to mind such minor masters as Sergio Martino or Michele Soavi. Officially, they don’t make movies like that anymore.