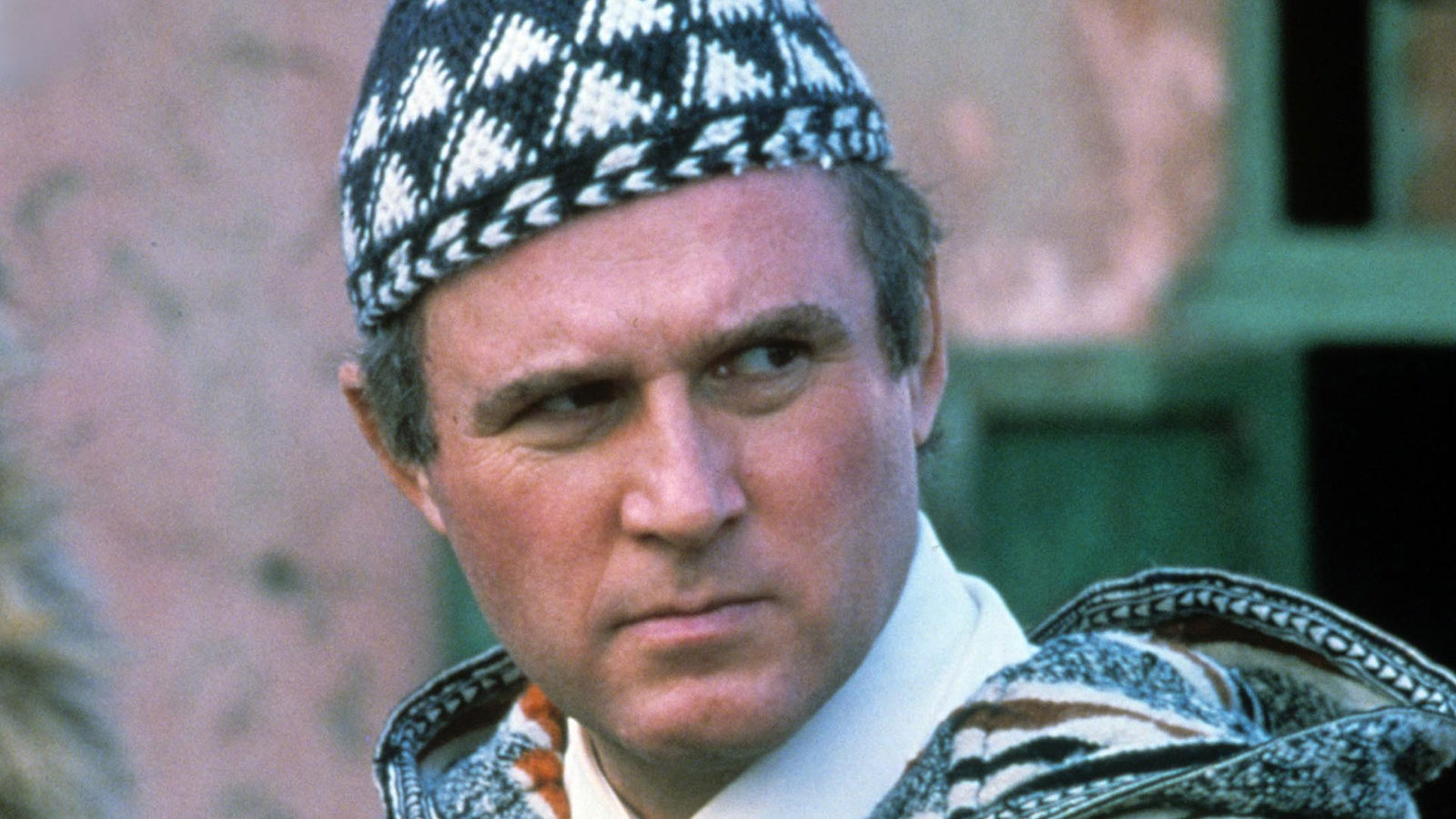

By Charles Grodin in the May-June 2006 Issue

Toward a Theory of Film Directing

The actor shares his personal take on the actor-director relationship

I've had some unusual encounters with directors.

From the May-June 2006 Issue

Also in this issue

In a picture I made early in my career, the director seemed to be on his way to making an important point when he suddenly fell asleep. I don’t think it was fatigue.

One director whom I liked very much personally seemed to have eight directions for every couple of lines. “When you turn at the door, do that thing you do with your eyes.” “What thing?” I asked. Definitely self-conscious-making.

Another director, also early on, seemed stunned when I suggested an alternative to what he had said. He was a European director. This was his first American picture. He clearly had not experienced give and take—only give.

Then there was the director who looked at me like I was certifiable when I asked, I’m sure politely, that he not comment on what he liked—as in, “Boy, you really nailed that last line”—but only if he wanted something different. General support and praise from a director is essential. Specific praise about a moment can make you nervous.

Once, when a young actress simply asked our director if she could walk over to someone one line later than he had asked, he stalked off the set and just sulked in his dressing room.

Being the senior member of the company, I decided after about 20 minutes to see if I could get him to come back to us. When I asked him what was going on, he said, “I’ve never had an actor question a direction of mine.” He had directed some very famous actors, so I just said, “Oh, come on, yes you have.” He thought for a long moment and rejoined us, as though nothing had happened.

Another time a director who was also acting in the movie told me I was being inappropriately funny. I again, I hope politely, suggested that I wasn’t, but that he might consider attempting more humor himself. He glared at me, then asked if I had any comic ideas for him.

On behalf of the actors in a movie with a lot of special effects, I asked the director if there was any way he could possibly give some thought to how long the actors were being kept waiting. It seemed to be about eight hours a day. He snapped, “You’re the highest-paid person in the movie!” It was as though he was saying the highest-paid should wait the longest. He then referred to me as “a Jewish prince,” and then, seeing the look in my eye, quickly referred to himself as “white trash.”

In one picture I was having a lot of difficulty because a still photographer was driving me nuts, constantly snapping away, while I was on camera and off, just talking to the director or another actor. The director really tried to help me but couldn’t. The producer overruled him. He just felt all those still shots were crucial. I spotted the photographer again on a picture I did about 12 years later. I didn’t have a problem with him then, because he had cut way back on his snapping.

Maybe my worst experience was with a director who seemed to be incredibly angry with everyone—including me. More than once I heard him tell his assistant, “Have our star come to the set now.”

Finally I asked him exactly what he was so angry about. He said it infuriated him that I and the other two leading actors had our own motor homes, and he didn’t. I told him he could use mine anytime he wanted. He then would regularly burst in, go to the refrigerator, guzzle down a container of orange juice or something, and then turn and leave without saying hello or goodbye. At the wrap party, if that wasn’t a hooker he brought with him, he sure could have fooled the rest of us. He danced wildly with her while drinking from a bottle of booze, like in some C movie. Toward the end of shooting, another actor accidentally broke my nose in a fight scene. When they had stopped the bleeding, I said, “Let’s keep shooting.” The director said, “You’re really showing me something!” I’m not sure what he felt I was showing him, but I’d said it not to be macho but just because I wanted to get the hell away from this guy as soon as possible.

Once on the first day of shooting of another picture, the director had me do a scene over and over again where I was supposed to run and stub my toe. I thought we got the shot right away, but he asked me to do it again and again, I think, to show me who was boss.

It was unnecessary, because there can be only one boss, and that must be the director.

Charles Grodin has appeared in more than 30 films. After a 12-year absence he will return to the big screen early next year in Fast Track, co-starring with Zach Braff, Amanda Peet, Jason Bateman, and Mia Farrow.