By Nick Davis in the November-December 2015 Issue

The Object of Desire

Todd Haynes discusses Carol and the satisfactions of telling women’s stories

An ice pick. An atomizer. A rose.

I scrawled these words in my notebook before swooning home from Carol, Todd Haynes’s consummate braiding of social diagnosis and emotional catharsis. Weather aside, there is something irreducibly cold about the world inhabited by Rooney Mara’s Therese Belivet, a shopgirl and aspiring photographer in early-Fifties Manhattan, and by Cate Blanchett’s Carol Aird, a well-to-do suburban homemaker. Carol’s impending divorce gets messier once her husband cites a vague “morality clause” in petitioning for custody of their daughter. Therese, whose boyfriend keeps pushing romantic trips and long-term commitments, finds that beginnings and middles of relationships can be as disorienting as conclusions. The two women meet, differently unprepared for the passion they soon feel for each other.

From the November-December 2015 Issue

Also in this issue

While capturing the chill of inhibited longings and New York winters, Carol chips away at its own shimmering surface, evoking the violence often required, toward oneself and toward others, to attain self-knowledge. The script, images, and performances all reveal sharp edges. At the same time, Carol is uncommonly delicate. Insights into character and theme feel diffused across the frame, not bundled into discrete objects or neat speeches. Haynes is too precise a semiotician to mount anything “timeless,” but even the piece’s most contemporary concerns—with sexism and sexuality, inchoate ambition, and alternative social arrangements—blend fully into its vision of mid-century malaise, as inseparable as the dancer from the dance, the red from the petal.

Elegant but thorny, Carol is the work of a director who has thought through every angle of his material. But whereas Safe (95), Velvet Goldmine (98), and Far from Heaven (02) translate such thinking into bold metafilmic spectacle, Carol finds Haynes standing at zero distance from the material, which is derived for the first time from someone else’s script, in this case written by Phyllis Nagy. While subduing his voice on screen somewhat, he is at no loss for words when asked about his latest feat.

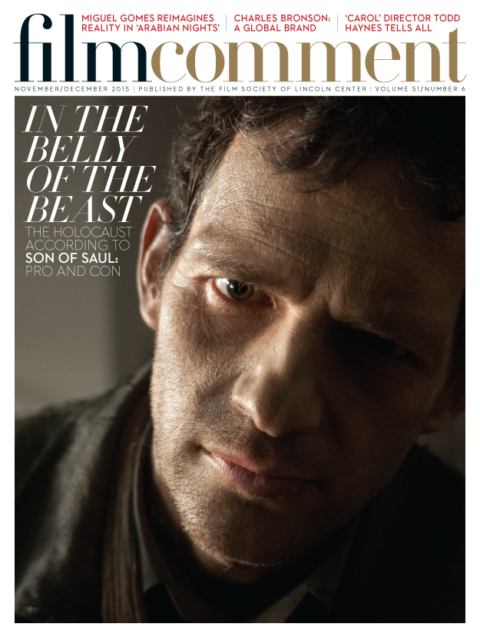

Carol

What movie would you nominate if someone new to your films asked where to start?

That’s hard, because they fall into categories: the melodramas, which are typically women’s stories, and the more exuberant, eccentrically structured films about musical artists. But I will say Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story [87], because in some crazy way it encompasses all those elements in my very first outing. It deals with questions about narrative, the subject, and identity, together with a take on pop culture in a particular historical framework. So that film brings all those concerns of mine into a tight, containable package.

For you, which throughlines across your body of work persist most strongly in Carol? And, conversely, what is the most self-conscious departure you made with this film?

Honestly, I was not even familiar with [Patricia] Highsmith’s novel when the script came to me. But what I immediately responded to was that it was a film about sexuality and gay or lesbian themes—all of which I’d dealt with in earlier films, even within the Fifties—but this was a different take on those subjects, which is what I’d been looking for.

The novel and Phyllis’s beautiful adaptation are such powerful love stories, and raised questions for me about how “the love story” in movies differs from the domestic dramas or melodramas I’ve looked at in the past. Plus, I was interested in the isolation of the desiring subject, who’s more in love, who’s more liable to be hurt by the object of desire—in this case, Rooney’s character, Therese. In the novel, you’re placed entirely in her point of view. The first draft I read of Phyllis’s script opened it up, giving us somewhat equal access to Carol’s side, where all the most dramatic material really resides—whereas Therese is just this young woman coming into focus, even to herself. There was something so strong about the entrapment you felt in the book of being stuck with Therese inside her own consciousness. I was really moved by that and wanted to bring some of that feeling back into the film.

I also saw a direct line from the overproductive mental states of all the criminals in Highsmith’s other novels to the romantic imagination, in its constant state of hyperproduction, conjuring scenarios and outcomes, getting overwhelmed by all the signs it’s trying to read, trying to determine whether the person you love feels any need to be close to you. That craziness, that loneliness, that paranoia, but also the pleasure of reading everything—to the point of total distraction from everything else—I found to be such a great premise.

How much were you inspired by other films from the era in which Carol unfolds?

Obviously one of the movies that influenced Carol was David Lean and Noel Coward’s Brief Encounter, with its methods for binding you to a character but also that structural doubling. In the beginning, the lovers are introduced as background figures whom you slowly realize will become the central players, especially the Celia Johnson character, who is its ultimate subject. Then you travel back as she recalls the entire experience of meeting Trevor Howard’s character, then you come full circle and return to that opening and discover what it was really about and what was at stake.

In Carol, toward the end, when you come back to the scene in the Ritz Hotel, Therese has been hurt, and has developed defenses and survival mechanisms to endure this experience she went through with Carol. So Therese’s disappointment is now the object of Carol’s reevaluation, as is the meaning of this young girl within Carol’s own life. We come back, then, not just to experience that scene a second time, but to do so from another character’s perspective.

Carol

That sheer “pleasure of reading” you allude to also informs how Carol operates formally, but in an unexpected way. As you’ve said, the plot of Carol intensely concerns everybody’s reading of everybody else. So what prompted you in this case to make the film’s surface less conspicuously “legible”?

Even though I wanted to feel rooted in a certain character—the more amorous, the more desiring of the two—I didn’t need that to be enacted by the language of camera. Some of the stylistic language I started to explore on Mildred Pierce [11] I wanted to continue examining in this. Some of it emanates from that beautiful mid-century color photography of Saul Leiter, with its tendencies toward refracting the frame, interrupting the frame, and abstracting the frame, but also the site-specific light conditions of being inside a café looking out on the snowy streets, or through a dusty bus window. Really, whatever conditions make you feel a sense of place and presence that was extremely specific and unique to photo-journalism from the period.

In looking at historical material from the period, what I found was a lot of photo-journalism and art photography, maybe not as dramatic or artistically liberated as Leiter’s, but so interesting—and a lot of it by women. I’m thinking of Ruth Orkin’s color photography of New York City, and Helen Levitt’s black-and-white stuff around that time, though she went on to do beautiful things with color. Esther Bubley’s color images inspired us, and then of course the recent discovery of Vivian Maier. All of it became a continuing language: the muted palette, the almost indecipherable temperatures, partly as a result of that palette but also because of how the city looked at this time. Not this cleaned-up, shiny, Eisenhower-era Fifties that I focused on in Far from Heaven.

We also looked at those black-and-white docudramas Ruth Orkin made with Morris Engel, the best known being Little Fugitive, but also Lovers and Lollipops. That one had locations that related much more to Carol: scenes in Macy’s, in the Museum of Modern Art, and in other New York City locations. Beyond the sets, though, these films informed our overall design, because they were all shot with natural light. I also shared Lovers and Lollipops with Cate and Rooney, and just the physicality of the central female character—very codified and limited in her freedom of expression, but combined with something very spontaneous and lovely—revealed a language of femininity that was very particular to this time and place. This became especially apropos for Therese, who is studying and practicing what kind of woman she is becoming. In that sense, this age difference between the women is as much an issue—well, maybe not “as much”—as their sexuality.

But it’s right up there, I think we can agree!

It’s right up there, in terms of how they relate, the tensions between them. Plus, of course, the class differences. All of that culminates in a real isolation Therese feels around Carol, even in the midst of this new, wondrous world that she’s falling in love with, which has this woman at the center of it.

I was taken aback by how Carol is, beyond a doubt, a film about the closet and its necessary circumspections but also by how much frankness manifests in the film. In that scene where Sarah Paulson’s character picks Carol up after a meal with Therese, I expected some prevarication about what this date entailed, but there is none. Within this circle, everybody knows. Even Richard, Therese’s boyfriend, talks about her having “quite a crush on this woman.” I had never seen a queer film set in this era that made so much room for a kind of transparency within certain company. It’s not as simple as “in the Fifties, nobody anywhere could say x about y.”

Granted, as contemporary viewers, we’re reading every overture with a kind of intentionality, questioning whether each exchange is crossing taboos or not, which is not always a fair judgment. But you do get surprised. The utter unrepresentability, the just unimagined notions of what love between women might look like and how it might be explored, actually allowed for conventions of, say, older women and younger women going to lunch, pursuing each other as friends. Even at the end, when Carol invites Therese to live with her, we know what that means, but in that time and place, it would probably be far more scandalous, if not intolerable, for an unmarried heterosexual couple to move in together in a new apartment than for a younger girl to start living with an older woman. So, absolutely, there were these surprising openings for mobility or freedom or at least indecipherability that allowed for some explorations.

Carol

Still, as bracing as I found these moments of relative candor, I love that we never quite know where Carol and Therese’s relationship is heading, or even if they know.

That tension is being carefully developed throughout the course of the story, leading up to the question of how they will eventually hook up, and when, or even, will they?

Or have they already?

Or have they already! They’ve been living in hotel rooms—who knows what has happened. In the script I first read, there was a more immediate rapport between the women, which I thought worked against the tensions in the piece. So some of that unease Phyllis and I restored from the novel.

Another thing she did was move the characters away from any bohemian circle. In the novel, Therese is an aspiring stage designer and Richard an aspiring painter. In our film, these characters are less exposed to alternative lifestyles, less exposed to bohemia, less exposed to positive examples of lesbian love relationships, which really puts them at a loss for what they were about to embark on. I preferred stressing Therese’s inability to even grammatically comprehend what this love means—this uncollated, unorganized sense of desire just coming at you.

Even when you’re not a lesbian in the early Fifties, new love feels that way. You feel like your unique discovery of your object of desire was destined, and nothing like it has ever occurred before, and your special knowledge of this person is what made it possible.

Over your career, you have been associated at different points with New Queer Cinema, with the “woman’s film,” with activist work, and with academic approaches to semiotics. Which of these reputations seems to govern how the industry or the audience currently perceives you?

For the most part, people notice my career’s obvious attentiveness to female subjects and the very great actresses I’ve worked with. And let’s face it, these days, anybody who is making women’s stories a priority is distinct from the ongoing, tiresome turn to the male spectator as our sole value. It’s a distinction I completely appreciate and feel I’ve earned and am proud to hold.

It’s not like I would mind being considered for all kinds of things. But I feel sated with the stuff I get sent, and it’s absolutely fine for offers to be largely curtailed along these lines. And actresses often bring me properties they are developing, which is great.

I cosign all of that, though I must add, there are so many men I have never liked better than in work you directed: Xander Berkeley in Safe, Brían O’Byrne in Mildred Pierce, Dennis Haysbert in Far from Heaven. Do you sense that men who act in your films feel they are working with a “woman’s director”? Is there ever any conversation along those lines?

I have had great experiences with so many male actors. But absolutely, in some cases where a film is driven by a woman, it is a bigger challenge to get men attached, especially when you’re seeking a “name” that might get the film financed. But I cherish the experiences I’ve had with Christian Bale, Heath Ledger, Richard Gere… We all shared an ability to get close very quickly. And yes, I felt I could offer them something unique, something that challenged them and forced the audience to revisit assumptions they might have about Richard Gere’s career, or Dennis Quaid’s. And God, Dennis Haysbert! He did such a phenomenal job with that role, and so fully understood the tenor of that period, and the almost musical quality of how that character needed to speak and move in Far from Heaven. That’s a collaboration I will never forget.

But really, I’m pleased if I’m doing anything to reinvigorate a discussion in movies about women’s stories, women’s status, and women’s experiences—and also, stories that aren’t by definition affirmative or heroic. My films may not make you completely comfortable with the outcomes. They raise questions about our lives, and about choices we do or do not have. If these kinds of stories find greater expression in domestic tales that are driven by female characters, then I’m thoroughly proud to be part of that tradition. And it is a tradition!