By Irina Leimbacher in the March-April 2008 Issue

The Body Politic

The films of Nicolas Klotz interrogate the new world order from the lower depths to the executive suite

The question in La Question humaine (07)—retitled Heartbeat Detector for its international release—is one of language. A corporate thriller of sorts, set amidst the offices, halls, and parties of the managerial class, Heartbeat Detector is also a philosophical inquiry into how we inhabit the language we use and how language, in turn, inhabits and uses us. It is a controversial and provocative film, one bound to unsettle audiences who take its questioning seriously and upset others who bristle at its core analogy. Like all of Nicolas Klotz’s recent films, it is a response to and comment on the present—the era of neoliberal capitalism, industrial downsizing, and the displaced and disaffected who do, or don’t, manage to adjust.

From the March-April 2008 Issue

Also in this issue

Based on the 2000 novel by François Emmanuel, Heartbeat Detector is narrated by Simon, an in-house corporate psychologist played by Mathieu Amalric, who is asked to investigate the erratic behavior of the company’s CEO, Jüst (Michael Lonsdale). Simon’s covert research, framed as an attempt to assess interest in forming an employee musical ensemble, leads him into obscure psychic and ultimately historical territories. In spite of various insinuations, Simon is never sure of the actual motive for the investigation. Is it genuine concern for the future of the company or a vicious power struggle among aging executives? Nevertheless, with Simon we discover traces of the repressed past that haunts Jüst, a past that then begins to haunt Simon’s relationship to the present—and our own. A series of anonymous missives leads him to an encounter with a disgruntled former employee (played by an ethereal white-haired Lou Castel), laid off during a recent downsizing. The letters, in which the language of Nazi technicians is intertwined with the language of corporate management, appear to be the work of an embittered worker, but they articulate, through their mad juxtapositions, a much more profound disquiet. It is this disquiet that ultimately binds the characters together and attaches each of them, and us, to history, while the hallucinatory textual collage poses the fundamental philosophical question of the film.

Klotz and his filmmaking and life partner, Elisabeth Perceval (credited with the screenplays), have been making films together for the last decade, and Heartbeat Detector is the third film in a collaborative trilogy. With a background in music documentary and theater, Klotz combines attention to socioeconomic realities, corporeal gesture, and music in an absolutely unique way. Indeed, Klotz and Perceval’s recent features mix fiction with documentary details to the point that real life sometimes erupts through the thin texture of the story and the narrative almost collapses under the sudden weight of the real. At the same time, musical interludes, whether sung performances or a letting go of mind and body through unrestrained dance, also periodically disrupt the forward march of the narratives. Klotz and Perceval’s collaborations are preceded by periods of intense field research that then informs the stories, dialogue, and mise en scène of the films. While quite different in cinematic style and subject matter, each of the three films of the trilogy—Pariah (Paria, 00), The Wound (La Blessure, 04), and Heartbeat Detector—interrogate the impact of the contemporary socioeconomic order on the lives and bodies of those either discarded by or caught up in it.

Pariah

The first two works focused on the discarded. The detritus of the new world order, what has been deemed its unavoidable and acceptable waste product, are those who can’t play by the rules: the unemployed, the homeless, and the illegal “aliens” wandering from one inhospitable country to the next. While Pariah accompanies a handful of people found drifting, drunk, or barely alive on the late-night streets of Paris, The Wound explores the world of an asylum seeker and the community she lives with during her first weeks in France.

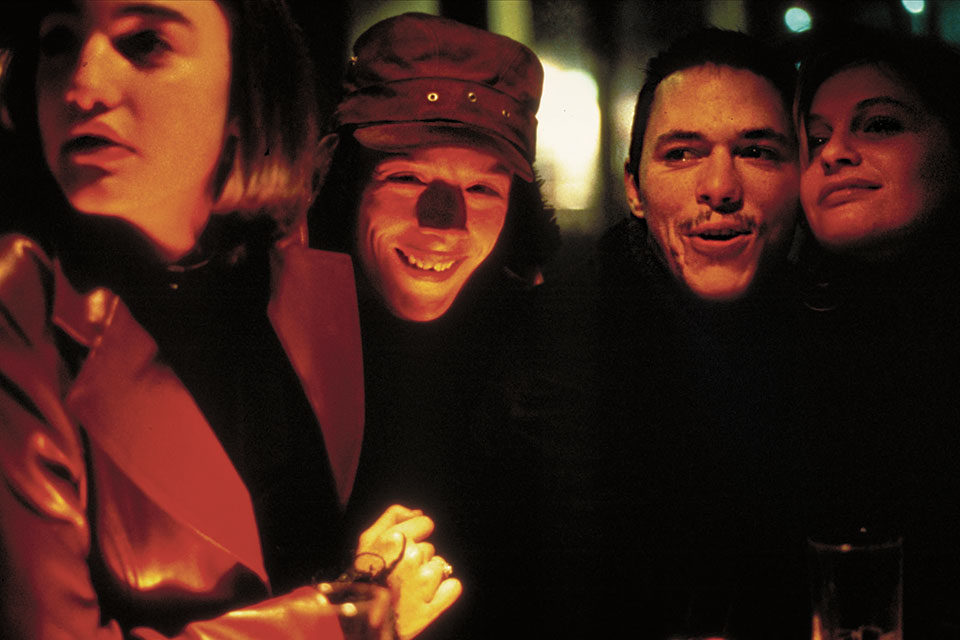

Pariah frames its fiction with a turn-of-the-millennium New Year’s Eve ride in a van operated by social services. The staff’s task is to pick up vagrants from various corners of Paris, give them chocolates, and deliver them, forcibly or voluntarily, to a homeless shelter outside the city where they can get medical attention and spend the night. Full of vitality and humor in spite of the sometimes harrowing subject matter, this lengthy opening gives way to a detailed exploration of two previous days in the lives of two of the van’s occupants, both young men, before returning to the present to continue through the night at the shelter and the following day. Shot mostly in low light and on handheld DV, Pariah often feels like, and sometimes is, nonfiction. The immensely compelling nonprofessional actors are people Klotz and Perceval met on the streets, and Gérald Thomassin gives a bravura performance as one of the young men—he’s reminiscent of a gentler Franco Citti in Pasolini’s Accattone.

Also produced with a mainly nonprofessional cast, The Wound centers on a group of African immigrants and asylum seekers in Paris. Blandine (Noëlla Mossaba) arrives at the airport from the Republic of Congo under an assumed name, and although her husband is eagerly waiting for her, she doesn’t appear. Instead, she and a dozen others are herded into a small holding cell and denied entry into France. The brutality of the immigration police is depicted in vivid detail, as is the protracted wait endured by Blandine’s community. Finally Blandine is allowed entry, bearing a huge gash on her leg sustained as a result of the officers’ callous treatment. Once at the squat where her husband lives, time distends and folds in upon itself, and we enter a different limbo: waiting for Blandine’s physical wound to heal, waiting to see if her psyche can adapt, waiting for her to decide if this life is worth living. A palpable tension is manifest throughout the film, due to its ever-slower pace and repeated digressions. We think the film will focus on individuals, but in fact its concern is with a community. We cross paths with dozens of people in the midst of the tasks of everyday life (cooking, cleaning, moving, fetching water), and the “plot” is interrupted by monologues from those who pause to recount how and why they are here. Like the film itself, theirs are stories of continuous journeys without apparent beginnings and certainly without ends.

The Wound

With Heartbeat Detector, Klotz and Perceval have moved into new territory, not only in terms of social milieu, the focus on a central character, a more linear narrative, and a more complex mise en scène, but also by incorporating well-known actors such as Amalric, Lonsdale, and Castel. While the principal and secondary characters are portrayed by actors, the filmmakers continue to work with nonprofessionals—casting young managers-in-training in many of the non-speaking parts—and their attention to the gestural and spatial language of bodies is still as strong as ever. Also as in the previous films, the friction between narrative momentum and moments of digression, quasi-Brechtian distancing, and musical release continues to unsettle the viewing experience.

Whereas the bodies in Pariah are tense and agitated (the film begins with an amazing “dance” by a drunk or stoned adolescent, pitching along the ledges and walls of a subway corridor), or broken to the point of motionlessness, and those in The Wound are mainly heavy with listless waiting, bodies in Heartbeat Detector are choreographed to reveal—or create—an aesthetics and ethics of corporate chic. Brief scenes in men’s bathrooms, elevators, office corridors, and waiting rooms have no narrative function other than to show how these bodies move, interact, mimic, and control themselves and others with the subtle coded gestures of a certain class and attitude. The excess of order and controlled restraint of the elite are countered in scenes at a nightclub and a rave where they go to relax, or in the less tidy movements of more ordinary folk. This choreography is also embodied narratively in the character of Simon, and Amalric does a superb job of manifesting complacency, misgiving, frenzied release, and the inertia of extreme distress in his posture, gestures, and the ways in which he inhabits space.

Klotz has said that the idea of making Heartbeat Detector came to him when, during the shooting of Pariah, he heard François Emmanuel reading extracts from the novel on the radio. The film he has made is as much about listening as about seeing, and the timbre and tone of Amalric’s voice play a crucial role. Evoking assurance or disquiet in his first-person narration and in his reading of the intermingled “technical” texts from corporate management theory and the Third Reich, Simon’s inner monologue periodically takes over the film. Finally attempting to resist one kind of language with another, he utters a melodious litany of his own over the black screen that concludes the film, a naming that evokes a multitude of stories, feelings, and lives. This endeavor poses the crucial question as to how language can engender imagination and empathy as well as serving to enhance organization and control.

Heartbeat Detector

The 1942 letter that surfaces at the climax is one that will be familiar to those who have studied the Holocaust or who remember parts of the same document as read, also in voiceover, by Claude Lanzmann at the end of the first part of Shoah. If one considers Heartbeat Detector’s inclusion of this text primarily as an indictment of corporate capitalism, then one will judge it as inappropriate, perhaps even unjustifiable. But I see it rather as the most extreme case of a certain use of language—the ultimate archetype of dehumanization in the interest of a technical efficiency that sees nothing other than itself. It is this horrifying use of language that the film warns against, forcing us to listen to it, asking us to consider when we should, or would, react. American audiences, perhaps less affected by rising unemployment and unfamiliar with recent cases of work-related suicide in France, might consider how our own language gets perverted by political and military establishments in terms such as “collateral damage,” “extraordinary rendition,” or “enhanced interrogation techniques.” Klotz and Perceval are asking us to listen to, and question, the languages of the word and of the body that, at least in part, determine what we accept as the “normal” course of events.

If the fact that Heartbeat Detector, like the earlier films in the trilogy, was made on a B-film budget explains some moments of awkwardness in the film, others are due to the filmmakers’ desire to remind us that we are watching an artifact, the imperfect product of human love and labor. A certain repetitive heavy-handedness in the articulation of the novel’s message carries over into the film, but Klotz and Perceval’s additions, as well as their eclectic use of diegetic music (Schubert, flamenco, fado, and New Order) and the score by Syd Matters, add flesh, blood, and sensory pleasures to this moral tale. As in their previous films, uneasiness is inherent to the spectator’s experience. Shaken by the recognition that what we are seeing and hearing is not always or only fiction, one is inevitably moved to react and question. What more can one ask from a film?