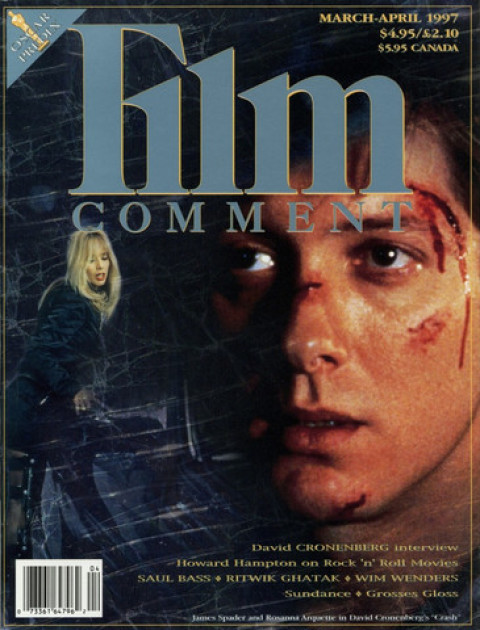

By Jacob Levich in the March-April 1997 Issue

Subcontinental Divide: Ritwik Ghatak

On the undiscovered art of Indian cinema’s maverick

If Satyajit Ray was the suitable boy of Indian art cinema—unthreatening, career-oriented, reliably tasteful—Ritwik Ghatak, his contemporary and principal rival, was its problem child. Where Ray’s films are seamless, exquisitely rendered, conventional narratives that aim for the kind of psychological insights prized by 19th century novelists, Ghatak’s are ragged, provisional, intensely personal, yet epic in shape, scope, and aspirations. With Ray, you feel safe in the hands of an omniscient, authoritative master. Viewing Ghatak is an edgy, intimate experience, an engagement with a brilliantly erratic intelligence in an atmosphere of inquiry, experimentation, and disconcerting honesty. The feeling can be invigorating, but it’s never comfortable.

From the March-April 1997 Issue

Also in this issue

Subcontinental Divide: Ritwik Ghatak

By Jacob Levich

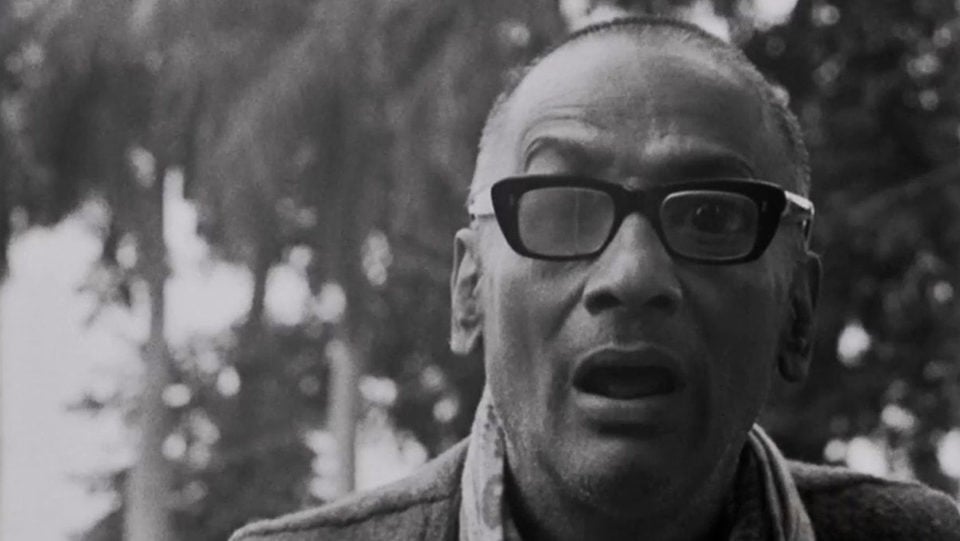

A committed Marxist, lay Jungian, sometime novelist, and notoriously self-destructive alcoholic, Ghatak (1925-’76) spent his filmmaking career in Ray’s shadow. While Ray fairly cornered the international market in Indian cinema, Ghatak struggled to finance and complete his few films, continually wrestling with a variety of personal and political demons. The bittersweet comedy Pathetic Fallacy (Ajantrik, ’57) was a modest success with Bengali audiences, but Ghatak never managed to produce a hit. He declined to exercise his considerable charm on international distributors or work the festival circuit. He alienated friends, political comrades, and business connections. He left major projects unfinished, bartered film rights for bottles of booze, and generally made a shambles of his life and career.

Subarnarekha

Ghatak’s already slim chances for fame and fortune were further attenuated by his political convictions. His debut, The Citizen (Nagarik, ’52), which critiques the Horatio Alger-esque ambitions of a naive young man in the slums of Calcutta, is an overtly Communist film, ipso facto out of the running for international accolades during the Cold War era. (The Citizen grew out of Ghatak’s work with the Indian People’s Theatre Association, an essentially Communist theatrical collective—briefly the cultural focal point of postwar Bengal—later lovingly caricatured in his E-Flat (Komal Gandhar, ’61). Although none of the later films hews to Party line, all are implicitly Marxist and revolutionary in spirit. And the director’s lifelong insistence on returning to the ugly facts surrounding Indian Independence—particularly the cynical and disastrous partition of Bengal—was as embarrassing to South Asia’s cultural gatekeepers and official hagiographers as it was mystifying to the Western variety.

Despite all this, Ghatak managed to acquire a small but remarkably loyal following among India’s left-leaning intelligentsia. Crucially, during his brief tenure as vice principal of the Film and Television Institute at Pune, he mentored a new wave of progressive filmmakers (including Mani Kaul and Kumar Shahani), many of whom were to become leading lights of India’s so-called Parallel Cinema during the ’70s. Ghatak’s death in 1975 went unnoticed outside India, but the faithful kept his legacy alive. That legacy—eight extraordinary feature films, a clutch of provocative shorts and documentaries, and scattered writings in English and Bengali—is now widely celebrated in India, but remains largely invisible to filmgoers internationally. Hence the palpable sense of discovery attending last year’s New York Film Festival, where, probably for the first time, all of Ghatak’s features were screened before American audiences.

To the uninitiated, these films came as a revelation. Each is a work of genuine distinction, marked by formal daring, intellectual vigor, and powerful emotional suasion. At least two of them—The Cloud-Capped Star (Meghe Dakha Tara, ’60) and Subarnarekha (’65)—are acknowledged masterpieces whose stature has only increased with time. A third, the virtually unknown A River Called Titash (Titash Ekti Nadir Naam, ’72), struck me on first viewing—I hope it won’t be my last—as a film of unqualified greatness. Taken as a whole, Ghatak’s work emerges as a force to be reckoned with by anyone who cares about world cinema, as well as a distinct challenge to Satyajit Ray’s preeminent status among subcontinental filmmakers.

Granted, Ray’s major achievement—his exhaustive, single-minded dissection of the world of Calcutta’s bourgeoisie—required subtleties of thought and exposition that were probably beyond Ghatak. But Ghatak’s limitless scope, freewheeling intelligence, and passionate political imagination permitted him to make startling connections that never would have occurred to Ray. With equal aplomb and obvious delight, he might forge a link between Brecht and the classical Sanskrit poet Kalidasa (E-Flat); suggest intriguing parallels between commodity fetishism and the primitive animism of Bengali tribals (Pathetic Fallacy); segue from sitars to a snatch of Beethoven’s Fifth in order to announce a mock-heroic theme (Reason, Argument, and Story/Jukti Takka Ar Gappa, ’74); or conjure a manifestation of the bloodthirsty goddess Kali amidst the blasted ruins of a WWII airstrip (Subarnarekha).

The Cloud-Capped Star

This brand of intellectual audacity doesn’t always work on screen, but when it does, it strikes home unforgettably. Ghatak’s third feature, The Runaway (Bari Theke Paliye, ’59), is superficially the most playlike of his films; its nostalgic evocation of Bengali village life, as well as its storyline—about an imaginative Brahmin boy, Kanchan (Param Bhattarak Lahiri), who runs away to the big city—are reminiscent of the first two parts of the Apu trilogy. It’s far from Ghatak’s finest work, but there’s a singular, characteristically subversive moment that throws the whole film, and Indian cinema in general, into fresh perspective. Toward the end of his wanderings, Kanchan is seen walking along the banks of the Ganges with his new friend, a tattered refugee. We’re given virtually the whole Orientalist package in one scene—mysterious allure of the East, lilting Bengali dialogue, juxtaposition of stark poverty with formal beauty, the river as symbol of Indian spirituality and timelessness, etc.—and we’re lulled by its familiarity. Then a tall man in a suit briefly enters the frame. He’s seen only from behind, but the position of his arms makes it clear that he’s filming the scene with a portable camera. An unquestionably American voice is heard to exclaim, “Quite a study, honey!”

Here’s an alienation effect that still packs a punch, even in an era marked by stylish self-reflexivity. We’re made to think, all of a sudden, about the commodification of Indian exoticism; about our own complicity in this process as consumers of Oriental images; about the dilemma of the Third World filmmaker, who must remain “authentic” even as s/he is required to package a culture, a nation, and a history in a form attractive to European and American audiences. After experiencing this small epiphany, the viewer may well begin to notice the film’s many oblique but telling jokes about the queer relationship between cultural center and periphery. (One of the best is an East-West inversion involving Kanchan’s dreams of escape to the primitive Amazon; his village may seem dreamily exotic to Western viewers, but it’s a dreary bore to him.) Today, such perceptions and strategies may be commonplace among the Post-Colonial Studies crowd; in 1959, they were novel and plainly radical.

At times, Ghatak’s distancing strategies may recall Bunuel or Godard, but he shares none of their icy detachment. Even in his satirical mode, Ghatak is invariably empathic and passionately engaged—much like Brecht himself, as opposed to the self-styled “Brechtians” who followed him. A case in point is The Cloud-Capped Star, a merciless, stunningly frank critique of the family-as-institution that is also one of the most heartbreaking movies ever made.

The Cloud-Capped Star

The story takes place in a lower-middle-class suburb of Calcutta, where Nita (Supriya Chowdhury), a schoolteacher of marriageable age, routinely postpones her own pleasure in order to support her family. She has a suitor, Sanat, but they have agreed to delay marriage until the financial situation stabilizes. Part of her meager income goes to underwrite the musical ambitions of her elder brother, a classical singer; the remainder becomes critical to the household budget after her father has a stroke and a younger brother is disabled in an industrial accident. At this juncture, Nita’s impending marriage becomes a threat to the family’s survival. Her mother responds by maneuvering Sanat away from Nita and toward her indolent younger sister. They marry; the family endures and finally thrives; but Nita is crushed, having sacrificed both happiness and health to the economic imperatives of domestic life.

There is infinite compassion in this darkly hued family portrait, but not a trace of sentimentality. One by one, the pretenses and pieties of Brahmin gentility are stripped away, until we arrive at the dirtiest family secret of all: that love and loyalty are conditioned by financial necessity. At each decisive turn of events, Ghatak rolls out conspicuous alienation effects, as though challenging the viewer to take his point. Some of these are justly famous—e.g., the sound of a lashing whip when Nita discovers Sanat’s infidelity, or the effect of bubbling cooking oil as the mother reluctantly resolves to destroy her daughter’s only chance of happiness. (The latter is an especially nice trope, illuminating not only the fact of simmering emotion but also its cause: the threatened loss of a meal ticket.) Ghatak uses alienation as it was meant to be used—not as a fashionable fillip, but as a way of underscoring the kind of rigorous truth telling we all pretend to want from artists, though we’re rarely very happy when we get it.

In The Cloud-Capped Star, Ghatak makes potent and unapologetic use of melodrama, brilliantly harnessing its metonymic force to connect the personal with the political. (He’d mastered the highly evolved conventions of Indian melodrama during a spell as a contract screenwriter in Bombay, where he wrote, inter alia, Bimal Roy’s Hindi romance Madhumati, ’55.) An even bolder experiment with the form is Subarnarekha, on its face a kind of potboiler about forbidden passions and familial strife. In the dark days following the Partition of 1948, Ishwar (Abhi Bhattacharya), a refugee from East Bengal, attempts to cope with actual and psychic displacement by assembling a makeshift family; his much younger sister Sita becomes a kind of daughter, while Abhiram, an orphan boy of uncertain parentage, is a surrogate son. Inevitably, the children (played as adults by Madhabi Mukherjee and Satindra Bhattacharya) grow up to fall in love; to Ishwar, their relationship constitutes a psychosexual threat that he cannot consciously comprehend. When, in the first of several Dickensian narrative coincidences, Abhiram is revealed to be lowercaste, Ishwar seizes the excuse to proscribe the marriage. In keeping with melodramatic logic, it’s the beginning of a downward spiral that ends in unspeakable squalor and tragedy.

A River Called Titash

High-minded critics attacked Subarnarekha for its plot contrivances and vulgarity, but Ghatak was unfazed. It was, he said, a Brechtian exercise in epic style; its melodramatic aspect was a deliberate means to an allegorical end. Indeed, like all the best film melodramas from Griffith to Sirk, Subarnarekha describes a complex metaphorical relationship between domestic discord and the maddening contradictions of the world at large. Thus Ishwar’s divided psyche stands in for the sundered nation, and vice versa; the experience of political exile is likened to the universal fragmentation of family and tradition under the postwar economic order (”We’re all refugees,” one character observes); the broken promises and irreconcilable contradictions surrounding the reconstitution of Indian nationhood are minored in Ishwar’s rumbling, doomed attempts to stitch his tattered family into the ideological fabric of Hindu patriarchy. As in e, the personal realm is revealed as fundamentally political; more importantly—especially for viewers whose exceptional privilege has insulated them from global upheaval—politics emerges as a personal matter, one of unconditional and overwhelming urgency.

Though it was released in 1965, Subarnarekha had been completed in 1962. An entire decade was to pass before Ghatak was able to finish another feature. Intermittently institutionalized for depression and alcoholism, he divided the remainder of his time between teaching, writing, and reading deeply in lung, whose theory of the collective unconscious he sought to reconcile with historical materialism. In this he was probably bound to fail, but ten years of otherwise fruitless speculation culminated in a film of surpassing strangeness and phenomenal beauty.

That film, A River Called Titash, was commissioned by the government of Bangladesh as part of an official effort to rebuild national identity following the break with Pakistan. Characteristically, however, Ghatak had other things in mind. Based on a well-loved Bengali novel by Advaita Malla Barman, Titash reinvents a straightforward pastoral romance as a microcosmic study of the complex interplay among natural forces, economic transformation, and rural culture. An East Bengali fishing community along the banks of the River Titash is in decline: the waters are drying up, and urban moneymen have begun to appropriate the bottomlands through legal chicanery and violence. In Ghatak’s hands, the story becomes a virtual case study in the devastation of peasant life by markets and modernity. But where a lesser filmmaker with a similar end in view would have used the language of documentary realism, Ghatak’s genius is to clothe his social analysis in highly stylized, even hypnagogic, imagery. (It is difficult to think of parallels to the film’s stark, literally breathtaking visual texture; imagine Woman in the Dunes stripped of existential portent and equipped with a social conscience.) The result is a visionary, uniquely seductive political film—one that sticks in the mind far longer than the customary forms of agitprop.

Reason, Debate, and a Tale

A River Called Titash was never properly released in India, and most local cineastes came to know late Ghatak only through his quasi-autobiographical final film, Reason, Argument and Story. Here, playing his own alter ego, the filmmaker is by turns querulous, hectoring, embittered, and pathetic. The performance is electric, and the autocritique is stunningly rigorous, but Ghatak’s swan song is perhaps the most abrasive and deliberately indecorous self-portrait ever committed to celluloid. It’s little wonder that contemporary audiences failed to respond.

Ironically, it is precisely the qualities that once struck cultural gatekeepers as uncouth that may end up recommending Ghatak to a new generation of filmgoers. His use of melodrama in the service of high art—a habit for which even his most fervent supporters once felt required to apologize—shouldn’t trouble audiences accustomed to the melodramatic strategies of Sirk, Fassbinder, Zhang, and Techine. Nor should his formal experimentation—anti-naturalistic sound, editing to sprung rhythms, eccentric focal techniques—be dismaying to members of the MTV generation.

His politics, too, may be due for a reevaluation. Now that the bogeyman of actually existing socialism is all but dead and buried, viewers may find it easier to understand the Communism of men like Ghatak for what it was—neither romantic delusion nor veiled sympathy for totalitarianism, but a “commitment to struggle rooted in a furious rejection of capitalism’s destructive tendencies. Indeed, to generations raised in a world where cataclysmic mass migrations, profound social inequality, and “ethnic cleansing” are fast becoming the norm, Ghatak’s preoccupation with Partition and its terrible aftermath may not seem so peculiar.

It would be unrealistic to expect that Ritwik Ghatak will ever be accorded the kind of prominence, accolades, and worldwide distribution given to Satyajit Ray. But it is to be hoped that some farsighted distributor will now choose to gamble on Ghatak, especially given the enthusiasm with which his movies were recently received in New York City. Following the retrospective, even the most jaded of Manhattan filmgoers would have had to agree with critic Partha Chatterjee: “You were either singed by the fire of his genius, overwhelmed by his passionate humanism and touched with his childlike simplicity; or simply repulsed by the arrogant manners, crass speech and melodramatic posturings of a prophet. Either way you had to react—to the mesmeric quality of the man and his films.”