By Alex Cox and Tod Davies in the March-April 2007 Issue

School of Hard Knocks: Charles Burnett interview

This interview was conducted in December 2002.

Tod and I were film students at UCLA in the late Seventies. I was a production student; she was a writer. We disagreed about most things filmic, with two exceptions: 1) X (a screenwriting professor) was a complete idiot, and 2) our most illustrious predecessor and role model was Charles Burnett. Burnett was an independent filmmaker who spent several years at UCLA, where he made two shorts and, in 1976, one legendary feature: Killer of Sheep.

From the March-April 2007 Issue

Also in this issue

School of Hard Knocks: Charles Burnett interview

By Alex Cox and Tod Davies

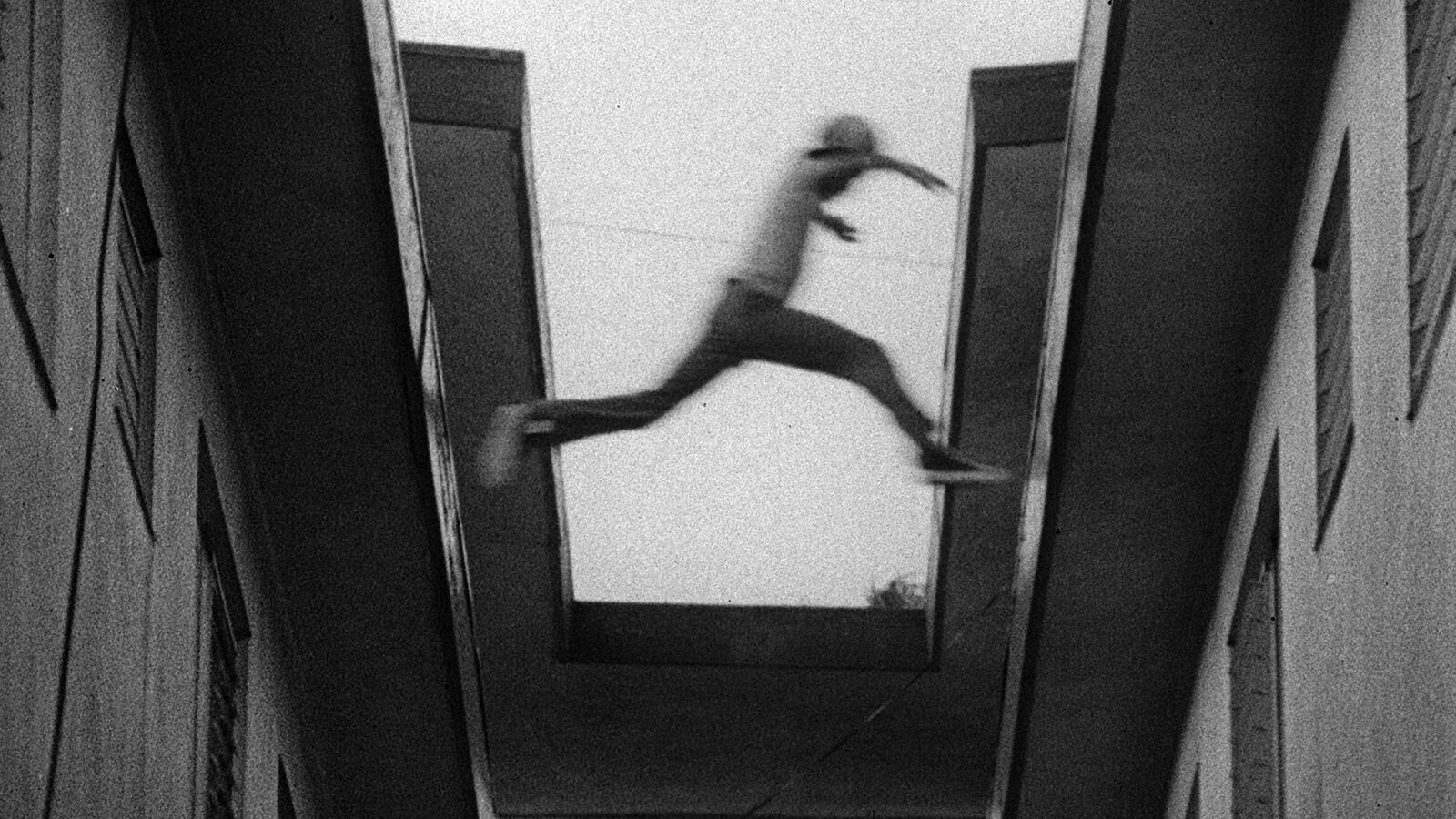

Killer of Sheep is the naturalistic-seeming story of a working-class family man in Watts. Shot, over a series of weekends, in magnificent black-and-white, its story is low-key, tragic, and often hilarious. The cast was entirely amateur; the film was crewed by a mixture of film students and local kids. It was made in an extraordinary context—a film school, UCLA, where in the Sixties and the Seventies you didn’t have to attend classes, or graduate. You just had to make films, using the vast facilities of the technical office and the Moviolas and flatbeds of the editing rooms. Of course, some students abused the process: they didn’t make films, they just hid out. But some extraordinary pictures were made by UCLA’s multicultural, radical crew—not little 10 minuters, like nowadays, but epics: 50-minute science-fiction movies, or even independent features, in the case of Burnett.

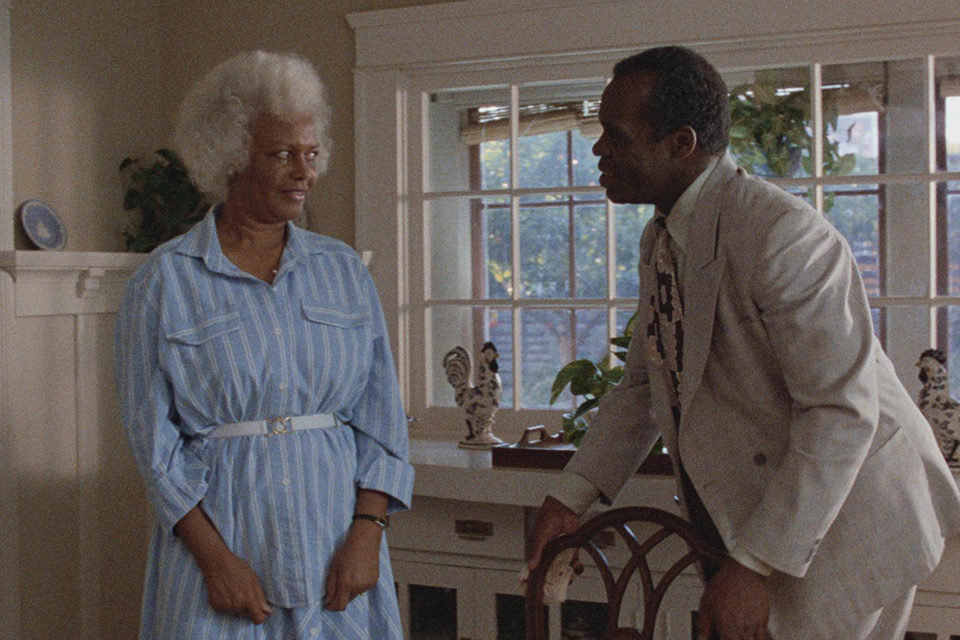

Seven years went by between Killer of Sheep and Burnett’s second feature, My Brother’s Wedding (83)—a film he describes as “unfinished.” His third film, To Sleep with Anger (89), had a Hollywood star—Danny Glover—and an infamous profusion of producers. It was supposed by some to be his entry into the mainstream. But that is not a stream where graduates of the “UCLA School” can swim. Burnett has had glancing but not fatal contacts with Miramax and Oprah, and gone on directing personal features such as his recent Annihilation of Fish (99). Recently he was in London; and when he heard we were showing The Revengers Tragedy in Oxford he was intrepid enough to risk the privatized railways to attend the screening. The train was an hour late; he missed all but the last half hour. But we were honored by his visit. Over tea afterwards (Burnett likes English tea! As does Davies… Is this characteristic of All Good Americans?), we talked about To Sleep With Anger, UCLA, and the marginal but compulsive world of independent films.

To Sleep with Anger

Alex Cox: How did To Sleep with Anger come about?

Charles Burnett: I was trying to get some money from PBS to do a film about a young girl who was killed in a very ironic way—ironic meaning that she was trying to help the law, and the law ended up not helping her. It actually allowed her murder to take place. I thought it was very tragic, and I wanted to do a film about this. So I submitted it to PBS, they agreed to do it, and then they just took the heart out of it… Anyone who gives you money wants to have their say. I said, “This is a real story, it’s not a fictional piece.” So I decided to do something else, and I wrote To Sleep with Anger. Thinking that it’s not real, so if they had any kind of input it wouldn’t be so tragic. I started to write it, and sent them different stages of it. And they brought in the same people, wanting to make it into their movie. The things that were cultural or specific about it, they wanted to take out. They wanted to make it “for the mainstream, so that everyone can understand it.” I said “that’s not the story; the story has to do with folklore, and the Black experience.” So we got into this huge argument again. So what the Corporation for Public Broadcasting—CPB—did was: they’d pay you after they approved a draft. You’d get involved with them, you’d get dependent on that check coming in, and they’d keep quizzing you on those changes. “Have you made those changes?” And you’d realize that the moment you made those changes, the check would come in the mail. Otherwise, you don’t get it. They don’t say it that way, but it comes out that way. So that became very difficult, and finally I said “I can’t make the changes that you want me to make; it’s not about that.” So we parted company, and they wrote a really nasty letter saying that I’m not a writer, and things like that. It was really awful! Then, this guy Cotty Chubb—he had been a friend of Michael Tolkin, who did The Player—called me out of the blue and said, “I hear you might be working on something; I’d like to see what you’re doing; I’m a producer.” I said “I have this script that no one wants,” and he said, “Bring it down.” So I dropped it off in his office. The day before, this guy Puttnam . . .

AC: David Puttnam? The English guy that ran the studio.

Head of Columbia at the time, yes. He had a missionary or a revolutionary something going at the time, and had put a bunch of young people together, who were into trying to find new talent. David’s office had called, and I gave it to them as well. They’d said, “We’ll get back to you in three or four weeks.” So the next day, Cotty Chubb calls and says, “I’d like to make the movie.” I said, “You serious?” He said, “Yeah, I’d like to try to find the money to make the movie.” A couple of days later, David Puttnam’s people called, and said, “We’d like to talk to you about it.” I said I’d already made a handshake deal with this other guy. Within a couple of months or so, the David Puttnam thing all fell down, because he was getting so much flack. Cotty had just done Cherry 2000—

AC: That was about a girl robot, right? I remember.

—and he started trying to find money for this, and got close, and not so close. Then he moved over to Ed Pressman’s office, which helped a good deal. And I knew some people who had just done a film with SVS—Sony Video Services, whatever it was. They’d done a lot of strange movies for video, and were interested in getting in with Pressman. They put some money into To Sleep With Anger—but then they were taken over by Columbia, and it was another ball game. It took a lot of people. We had 12 producers on the show. There was something written about it in the trades, and a piece in The Wall Street Journal about this little biddy movie with 12 producers, as if it didn’t take so many people to make the film. But, in a sense, it did—you knew someone here who had some money, or knew someone who knew someone who had some money, and by the time every connection was made, there were all these people attached to it. But it never made any money. Goldwyn took it over, which was a good and bad thing. Bad in that they didn’t do anything with it, didn’t know how to market it. We had battles about it. They refused to take any advice. There was just this arrogance. So the film never really got an audience, was never shown in more than 18 theaters.

To Sleep with Anger

AC: You had 18 prints? Wow!

No, it was 18 different theaters. They took the same print and they showed it 18 times.

AC: The last film we did, we had one print.

One print…

Tod Davies: You saw it. Three Businessmen. We have it sitting in our office.

AC: When you became a director, did you have any expectation of making any money?

No. That wasn’t the idea. We thought that would be some sideline, something you did in addition to making films. It wasn’t daunting or scary or anything like that; it was expected, that if you want to make films you’re gonna have to do it on your own.

AC: And be relatively poor.

I think part of it came from the UCLA experience. “Here’s a camera, go out and do it.” It made you think that everything was possible. Because you could do it, and you proved it, over and over again. If I’d gone to USC I’d have a different way of viewing things. I’d have thought of things as more complicated, of having to have different things in place before I could do anything.

AC: If you’d been at USC you would have been channeled into being a cameraman, or a screenwriter. Something specific.

I went to UCLA to initially be a cameraperson; at USC I would have ended up staying that.

AC: What’s your impression of UCLA now?

It’s different. Everything culturally, societally, has changed. At UCLA in the Sixties, you thought about World Cinema—whether it was films from Poland, or Czechoslovakia, or Japan. It was like your backyard; you were as aware of Kurosawa, Truffaut making films as you were of some local person. You were waiting for the next film by these people. That doesn’t exist any more, for a whole bunch of reasons. At that time at UCLA you looked at film as an art form, as a means of expression. Not so much for entertainment, it was to do and say something. Now, when you go back there, it’s “How can I get into Hollywood? How do you do get an agent? How do you sell your first script?” The whole culture has changed. It’s a business now, and I think people are more aware of it as a business. I wasn’t aware of it as a business.

To Sleep with Anger

TD: On the film we just did, one of our trainees was from an art school. He said his teacher told him that films are like a brand, and that the director is like the one percent latex content in lycra.

What?

AC: In bicycle shorts.

What school is that?

AC: LIPA. It’s a performing arts school, but this student’s more into the business management side.

TD: And he’s a very smart kid.

I think that’s the way it is. That’s the way students are now. You find it in TV. In TV a director’s nothing. TV is created by a producer and a writer. As a TV director, you’re lucky if they allow you on the set. And film, because a lot of people are coming from TV to serious film, they’re bringing that model with them. The thing about it is, they don’t want people with any talent, or any particular point of view. Because they can’t control you. They want people who can be an extension of themselves. I was talking to a guy who wanted me to do a film with him. And he says, “I have this film, and we’re trying to decide whether we want a young person, or a seasoned person. If we went with a young person, then we’d be telling him what to do. We don’t have the time to do that on this film.” So they’re looking at me, now, right?

TD: We really need to stay in touch, because one needs to support one’s fellows in a world like that. We need to stick together more than we do.

I know. If only people would stay in touch. Because the ones who are surviving are the ones who make these films that don’t express any culture, or anything. Just, like, whatever the guys at the top say, that’s it. And this wave, that was, like, a bit obvious in the Sixties and the Seventies, has dissipated.

AC: If Nike came to you and asked you to direct a commercial for them, would you do it?

Let me put it this way: if Nike asked me to do a commercial, I would do it. Because it’s nothing. It’s not about me creating. It’s like: “Here’s a check, sign it, fine.” But if Nike said to me, “We want to do your movie,” or if the studio ask me to do a studio movie, no. No way. Because I’ve done TV, and it was murderous.