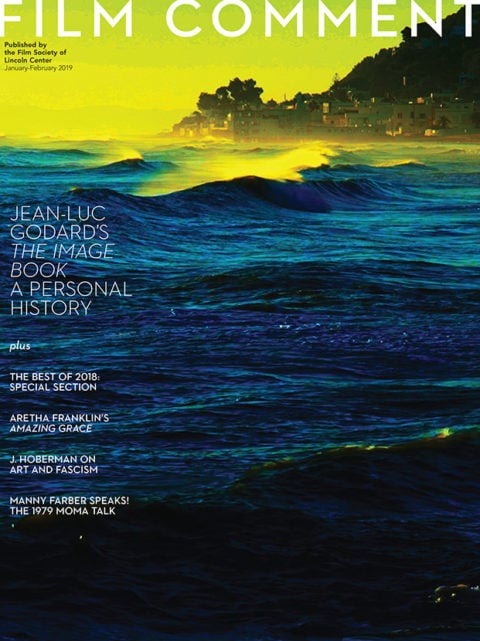

By Nellie Killian in the January-February 2019 Issue

Readings: Warriors at Work

Female filmmakers relate their efforts to make movies and forge a genuinely "new" Hollywood

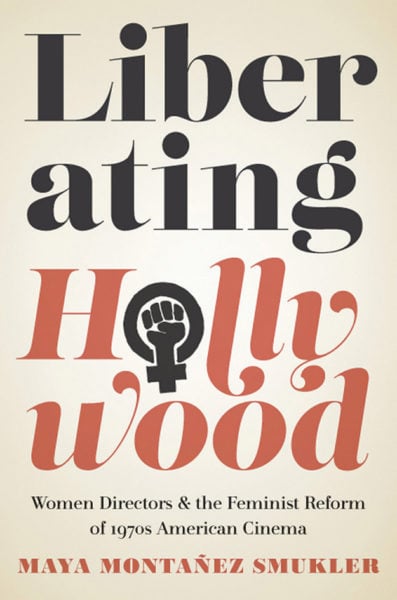

In the 1970s, the door to feature filmmaking in Hollywood was forced open just wide enough for 16 white women to get in. In Liberating Hollywood: Women Directors & the Feminist Reform of 1970s American Cinema, Maya Montañez Smukler traces the intersection of civil rights agitation, labor history, and a changing marketplace that made it happen, as well as the individual experiences of the women who were allowed to make films on a commercial scale. Relying on oral histories with the directors and their collaborators whenever possible, the heart of Liberating Hollywood are Smukler’s studies of each of the directors in question: Penny Allen, Karen Arthur, Anne Bancroft, Joan Darling, Lee Grant, Barbara Loden, Elaine May, Barbara Peeters, Joan Rivers, Stephanie Rothman, Beverly Sebastian, Joan Micklin Silver, Joan Tewkesbury, Jane Wagner, Nancy Walker, and Claudia Weill.

From the January-February 2019 Issue

Also in this issue

United by a shared moment of circumscribed opportunity, the women worked in vastly different idioms, from independent art films premiering on the international festival circuit to studio comedies and “new woman” dramas to exploitation fare. However disparate their milieus, many shared the same frustrations: the struggle for recognition, paternalism, lack of training and sufficient support, the impenetrable boys’ club of mentorship and patronage, heightened scrutiny, the pressure of representing an entire gender… all ultimately for paltry professional rewards. Smukler locates these filmmakers in a paradox of progress: invited into an environment that was still brutally, institutionally hostile to their presence. Many of their works were butchered; when a film did well, many found themselves pigeonholed. Some found work in TV; others stopped directing. It would be a depressing read if all the women weren’t such inspiring, endearing interviewees. (Elaine May, quoted from a stage Q&A: “Clint Eastwood can do anything because he’s tall and they respect him and in that way it’s better to be Clint Eastwood than to be a woman in Hollywood.”)

United by a shared moment of circumscribed opportunity, the women worked in vastly different idioms, from independent art films premiering on the international festival circuit to studio comedies and “new woman” dramas to exploitation fare. However disparate their milieus, many shared the same frustrations: the struggle for recognition, paternalism, lack of training and sufficient support, the impenetrable boys’ club of mentorship and patronage, heightened scrutiny, the pressure of representing an entire gender… all ultimately for paltry professional rewards. Smukler locates these filmmakers in a paradox of progress: invited into an environment that was still brutally, institutionally hostile to their presence. Many of their works were butchered; when a film did well, many found themselves pigeonholed. Some found work in TV; others stopped directing. It would be a depressing read if all the women weren’t such inspiring, endearing interviewees. (Elaine May, quoted from a stage Q&A: “Clint Eastwood can do anything because he’s tall and they respect him and in that way it’s better to be Clint Eastwood than to be a woman in Hollywood.”)

Smukler bookends the women’s stories with a meticulously researched industrial history of women’s reemergence as directors in Hollywood from the 1960s through the early ’80s, as the newly formed Equal Employment Opportunity Commission offered legal recourse for women and men of color to challenge the industry’s dismal hiring practices. She charts the process of holding the studios and DGA accountable to hiring standards, with both institutions in full self-preservation mode using PR black magic to obfuscate through endless pronouncements of their good intentions while claiming their First Amendment right and artistic responsibility to be free of any affirmative action requirements that would regulate hiring.

Smukler sees the increase of independently produced features in the ’80s as a turning point for women no longer at the mercy of a slow-moving studio system. She’s right, though working independently puts the onus of proving artistic and commercial viability directly on individual artists’ shoulders, dependent on a world of potentially prejudiced funders with no centralized power to reform, however incrementally. That said, it’s impossible to read Liberating Hollywood and not recognize the progress that has been made, even though too much remains sadly familiar. It’s still rough out there, but histories like these keep me moving forward.

Nellie Killian is a film programmer based in New York.