By Michael Koresky in the January-February 2019 Issue

Outside the Main Stream

The movies we love are ours forever—or are they?

In November, FilmStruck was struck its fatal blow. For those unaware, the dearly departed U.S. streaming service, which launched in fall 2016, was a coproduction of Turner Classic Movies and Warner Bros. Digital Networks; in addition to its deep catalog of Hollywood classics, American independents, and international rarities, it featured an exclusive channel programmed by the Criterion Collection. That sounds impressive on paper, but nothing could compare to the awesome, even overwhelming experience of simply browsing FilmStruck. If scanning the collections of other streaming services could be likened to panning for gold, looking for something to watch on FilmStruck was like swimming through Scrooge McDuck’s treasure vault. No matter where your search began or ended, you were going to find something worthwhile—or, often, revelatory—whether you wanted to watch Casablanca for the 117th time or that Chantal Akerman film you’d long been meaning to get to.

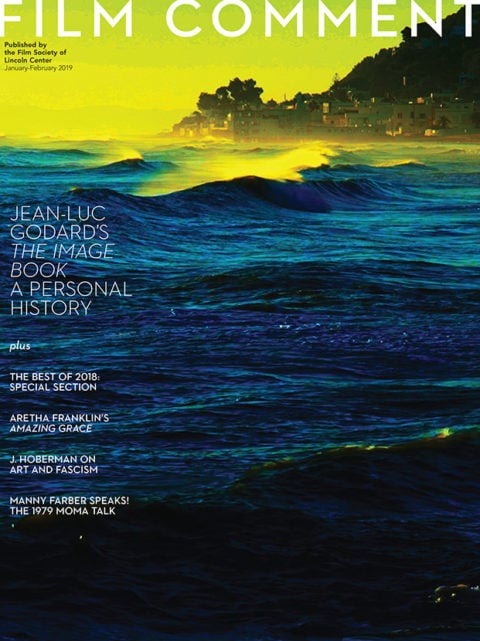

From the January-February 2019 Issue

Also in this issue

Then it all went away. On October 26, it was announced that, following AT&T’s acquisition of Time Warner Inc., FilmStruck—a “niche service” per a salt-in-the-wound statement from Turner and WB—would cease operations. Around 9 a.m. on the morning of November 30, it was accomplished. Our queues were wiped, our movies-in-progress deleted, our movie hunger unabated. For this loyalist who watched until the bitter end, it occurred with seven minutes left of Fellini’s hell-bound Poe adaptation Toby Dammit (1968), right in the middle of Terence Stamp’s climactic death drive. I couldn’t have picked a more appropriate film, which, as had so often been the case with FilmStruck, was a title I just happened to alight upon while casually perusing the digital aisles.

Criterion was mercifully quick to reassure subscribers that its own independent channel was forthcoming—a relief considering that Warner’s later-announced “three-tiered streaming service” sounds needlessly megalomaniacal. We always knew this era’s promised democratization of content would mean having to pay for multiple individual channels owned by territorial conglomerates. But it still stung when faced with the reality that, at the push of a button, a corporation could make our Ozu disappear.

Toby Dammit

We’re in a moment in which every apparently too-good-to-be-true initiative proves to be just that, and this continues to feel particularly sensitive—and anxiety-making—for a passionate film community. We yearn for a sense of togetherness beyond Twitter babble, and we don’t want to be reliant on industrial power structures to enjoy art. The once cinephile-centric streaming service Fandor changed its strategy in 2017, with its CEO Larry Aidem quoted in IndieWire as looking to expand its reach from “cineastes to Movie Fanatics”; on December 7, 2018, it laid off its staff and sold its assets. And don’t forget 2018 was also the year of the skyrocket rise-and-fall of MoviePass, a theatrical Shangri-La for the wallet. The skepticism with which even MoviePass’s most devoted members—both suburban families looking for an affordable night out at the movies and city-dwelling cinephiles pinballing all over town on the repertory circuit—viewed its business model didn’t make its burnout any easier on them.

The question of how we watch movies has always been tied up in economic factors, so these matters should be nothing new. But where and how we watch old films has perhaps been taken for granted. Since the early ’80s, there has been a myth of accessibility around home video. The moving of everything to an ethereal, digital sphere has only made the movies’ fragility feel all the more acute, and the question of what to do about it more urgent.

The loss of FilmStruck has been overstressed by some (perhaps by yours truly!), and underplayed by others (most dramatically in a provocative if hasty Washington Post essay by film academic Katherine Groo that used its demise as an occasion to query the canon and stress the importance of public film archives). The abundance of grieving, performative and otherwise, that flowed out in response to the announcement brought together a wider group of cinephiles than would normally share the same table, even inciting a failed petition to save FilmStruck that was signed by none other than Barbra Streisand. Now that it’s gone, its cultural value—you could see the films of Katharine Hepburn and Cheryl Dunye—remains clear, but what that value means for film’s future is less distinct.

That the Criterion brand—which has always felt both educational and expansive, curating the fundamentals of film history while offering alternatives to the canon—has remained undiluted throughout such a constantly transitional, tumultuous period is surely aided in no small part by the persistence of physical media. Yet nothing is built to last. Should we stockpile discs like water bottles and wait for the impending media apocalypse? Should we just turn to streaming services like Kanopy, whose ever- growing collection of art-house, classic, and mainstream cinema is accessible with your public library card? Or, for those of us privileged to afford them, should we just keep watching the other channels clogging up our Apple TV home screens—from the behemoths (Netflix, Hulu, Amazon Prime) to the niche subsets (MUBI, Shudder, Dekkoo, Crunchyroll)—waiting for the inevitable zap-out? No answers, but the death of FilmStruck at the very least has made us all feel a little uneasy. The cloud can’t save us; the world isn’t one big archive. We’re all just the owners of our own private collections, and hopefully one day they won’t only be accessible in our heads.

Michael Koresky is the Director of Editorial and Creative Strategy at Film Society of Lincoln Center; the co-founder and co-editor of Reverse Shot; a frequent contributor to The Criterion Collection; and the author of the book Terence Davies, published by University of Illinois Press.