By Chris Norris in the July-August 2003 Issue

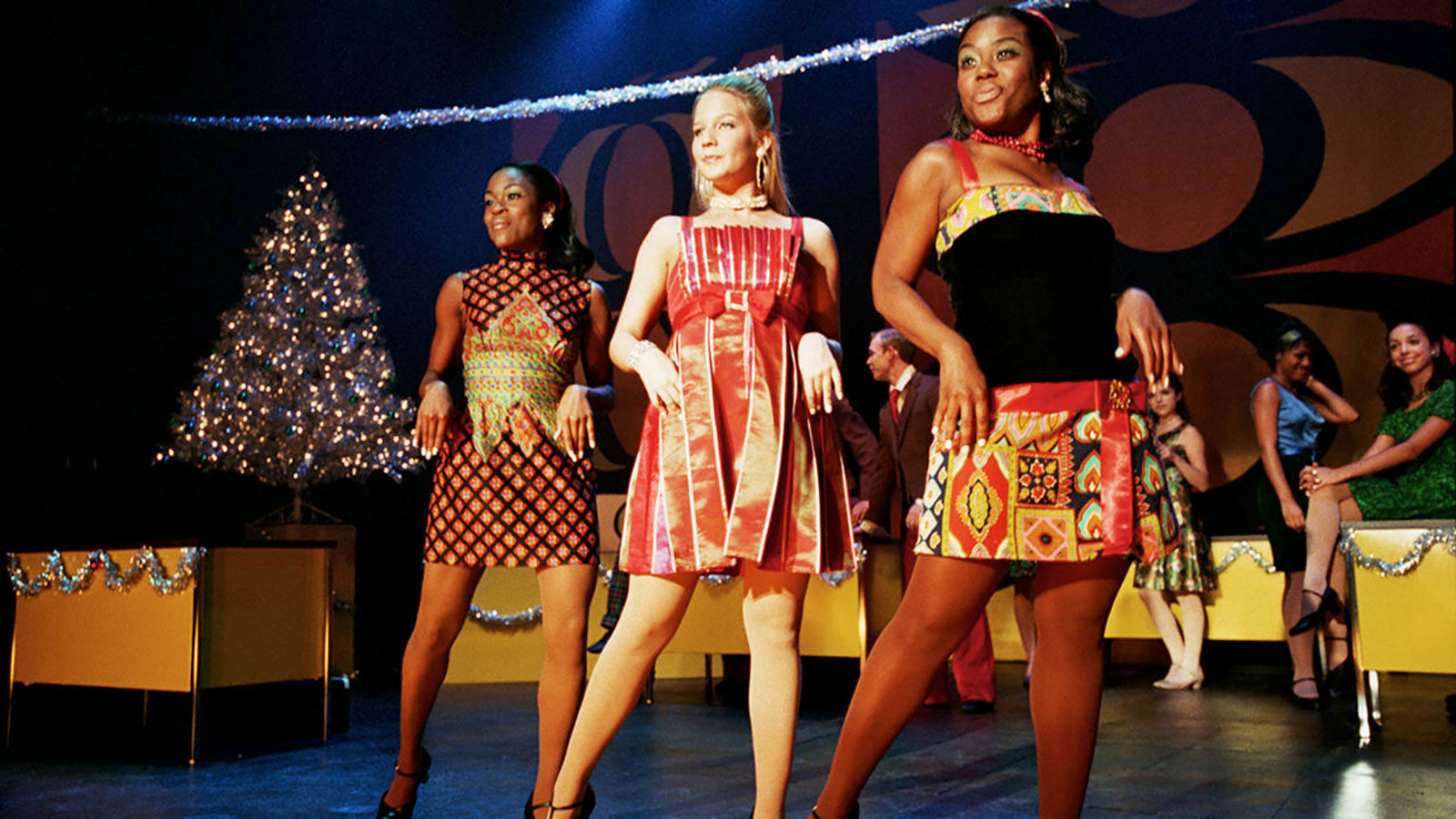

Movie of the Moment: Camp

Feeling the exuberance of an all-singing, all-dancing, and (almost) all-gay slice of teenage life

Of all the underserved communities in Teen-Film Nation, surely the most neglected is that class of effusive, hysterically self- involved youngsters that folks tend to dub “theatrical.” That the non-euphemism is usually “gay” may account for Hollywood’s trepidation thus far, but also for the great promise of the subject. Sure, jocks, nerds, and cheerleaders all have their gay members, but no group can make quite the ecstatic, scenery-chewing spectacle of the genre-requisite Search for Self as those whose nirvana involves footlights, jazz hands, and Sondheim. Only true sexually confused drama geeks can half-credibly say, “Hey kids, let’s put on a coming-of-age movie!”

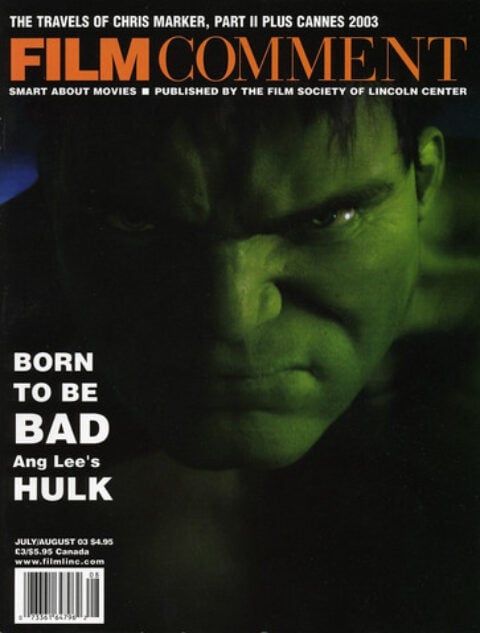

From the July-August 2003 Issue

Also in this issue

Thus, Camp. A sweet, clumsy, revelatory film set at a summer camp for showbiz kids and related misfits. Based on the Catskills’ actual Stagedoor Manor—alma mater to Robert Downey, Jr., Natalie Portman, and the film’s writer-director, Todd Graff—the training-ground setting enables an unlikely blend of Fame, Meatballs, and Paris Is Burning, following a cast of aspiring stars as they suffer crushes, gender crises, and other adolescent torments while belting out showstoppers in the mandatory 40 productions per summer. Starring a cast of all-singing, all-dancing unknowns, Camp is a deceptively strange species of film, a kind of indie metamusical, its stock plot devices and WB-level characterizations redeemed by an affectionate, penetrating glimpse into its charming and cultish milieu—J-Lo-era teens who clutch the Chorus Line soundtrack to their hearts, dreaming of a glitzier, more soigné world.

We meet the three principals on prom night. Ellen (Joanna Chilcoat), smart and suitor-less, is begging her brother to pose as her date. Michael (Robin de Jesus), Latin and gay, is getting the shit kicked out of him for arriving in drag. And Vlad (Daniel Letterle), a blond Abercrombie dreamboat, is primping in a tux—gazing into the mirror and performing one of American drama’s great monologues: Dirk Diggler’s Boogie Nights acceptance speech. “I only am who I am cause I was born that way. I have a gift,” he says, nailing the scene with a full Wahlbergian kung-fu flourish. All three compulsive performers soon meet at Camp Ovation to form the vertices of a knotted, Felicity-style romantic triangle, which unfolds between production numbers from Dreamgirls, Company, Follies, Promises, Promises, and other later-Broadway classics.

“If he’s gay, I’m Tyne Daly,” mutters a male camper when Vlad enters the bunkroom, guitar case in hand. Suspicions are confirmed at his audition when, instead of, say, “Don’t Rain on My Parade,” Vlad sings the Stones’s “Wild Horses”—prompting a counselor to gasp, “A boy! An honest-to-God straight boy!” As the smitten Ellen soon tells Vlad, “A guy like you could have a lucky summer in a place like this.” But also a confusing one. In the kingdom of the drama queen, the straight white boy is canvas—a blank screen on which to project all manner of fantasies, hang-ups, and resentments. In other words, your average American minority—or performer. And like the requisite white heartland naïf in your standard Real World cast, Vlad will be forced to reassess a lot, including his sexuality and quest for stardom.

A framed portrait begins the education. “Is that your dad?” Vlad asks, pointing at a photo on his roommate’s desk. Chuckling, Michael IDs the school’s unofficial patron saint, Stephen Sondheim. This is, after all, a summer camp where the hale sports counselor is a tragic figure, doomed to shoot hoops alone in an empty basketball court. Much of the dialogue cleverly explicates the sociology of this alternative universe, often through the outsider’s moments of culture clash. (Vlad: “Have you ever experimented with heterosexuality?” Michael: “You mean sleep with a straight guy? Why?”) Later, when Michael confesses to bedding a female camper only to seduce Vlad, the object of his affection does not know how to respond. “With a strait-jacket perhaps?” sighs Michael. While these teens speak with the improbable self-awareness of a Dawson s Creek sophomore, the notorious precociousness of real showbiz kids helps make their speech believable—or at least an occupational hazard, affected by the urbane lyricism of the Sondheim-era songs that surround them.

Read the full article in the July/August 2003 issue.