It was the last century’s impossible dream: a double vanguard, radical form in the service of radical content. There were moments—the Soviet silent cinema, Brecht’s epic theater, Surrealism perhaps, the Popular Front anti-fascism of Guernica and Citizen Kane, the promise of underground movies. And then, from the very back of beyond and close to the fashionable heart of international modernism, for a half dozen years from the mid-Sixties to the early Seventies, there was Hungarian filmmaker Miklós Jancsó.

The Round-Up

First manifest in The Round-Up (65), Jancsó’s boldly stylized film language appeared to be a synthesis of Antonioni (elegant widescreen compositions, austere allegorical landscapes), Bresson (impassive performers, exaggerated sound design), and Welles (convoluted tracking shots, intricately choreographed ensembles), even as his free-floating existential attitudes and “empty world” iconography evoked the theater of the absurd, albeit without the laughs. Jancsó’s subject or, rather, his prison, was history. His narratives recalled the literature of extreme situations-pivoting on cryptic betrayals, mapping the seizure of power, dramatizing the exercise of terror- and his politics were ambiguously left, perhaps crypto-Trotskyist.

How the Partisan Review crowd might have loved Jancsó, had they only been watching movies. So far as I can tell, the only one of the New York intellectuals—Stanley Kauffmann, Dwight Macdonald, Susan Sontag—to comment on The Round-Up when it turned up at the 1966 New York Film Festival, its blurb referencing Bresson and “In the Penal Colony,” was Manny Farber. He called it “a movie of hieratic stylized movement in a Kafka space that is mostly sinister flatness and bald verticals . . . Jancsó’s fascinating, but too insistent, style is based on a taut balance between a harsh, stark imagery and a desolate pessimism.”

Pessimism or realism? Jancsó’s twin compulsions are to simplify and withhold. His film form may be universal but his narrative content is often barely decipherable outside the arcane realm of Hungary’s history or its cultural politics. As the 20th century dawned, Jancsó’s homeland was Austria’s junior partner in the Hapsburg Empire. After WWI (which it fought on the losing side), the new nation was a short-lived Communist republic and then a military dictatorship; during WWII, Hungary was a Nazi terror state. After that (having once more allied itself with the losers) it became a short-lived parliamentary republic that segued into a nightmare Stalinist people’s democracy. Communist rule was interrupted by another glorious revolt, the bloody trauma of 1956. Russian tanks crushed Hungarian freedom fighters 50 years ago this fall, but then, after a time, the country was permitted to become the Soviet bloc’s most modest and humane form of really-existing socialism-at least until the bloc dissolved in 1990.

Hungary’s divisions ran through Jancsó’s family. He was born in 1921, the son of a Hungarian father and a Romanian mother, with Jewish relations on his mother’s side, and was raised in a village 20 miles up the Danube from Budapest. He received a Catholic education but converted to Communism, joining the Party in 1945. Jancsó was something of a perpetual student, having variously applied himself to law, art history, and ethnography (including a period of fieldwork in Transylvania), before entering the Academy of Dramatic Art. A documentarian throughout the Fifties, he didn’t find himself as a filmmaker until, at 44, he made what was immediately recognized in Hungary as perhaps the greatest film ever made there.

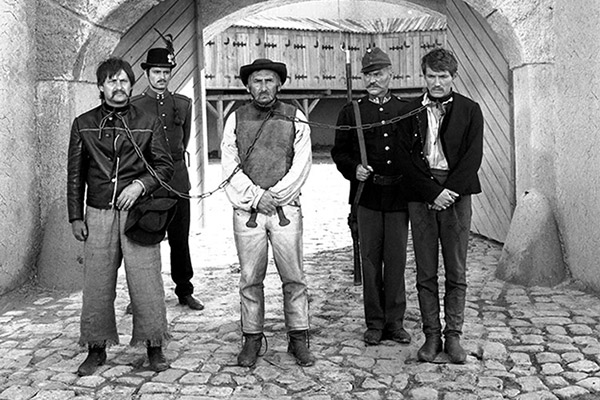

The Round-Up

The Round-Up is set in the late 1860s. It is 20 years after Lajos Kossuth’s failed revolution against the Hapsburgs, and remnants of Kossuth’s army still roam the Hungarian countryside. Austrian soldiers detain entire villages to uncover the individual partisans concealed among them. The Round-Up concerns one such mass arrest, and the complex round of interrogations and betrayals that inevitably ensue.

The rhythms are hypnotic. The viewer is at once hemmed in by and outside the action. Most of the often-cryptic scenario is confined to a wooden fort—a gingerbread house concentration camp, stark as a Grotowski stage—on the vast expanse of Hungary’s central plain. In the middle of nowhere at the edge of infinity, Austrian automatons in operetta uniforms play endless cat-and-mouse mind games with the exotic, impassive peasantry they’ve corralled. (Perhaps not so exotic: seen in the light of Guantanamo and Abu Ghraib, the image of hooded prisoners being marched in a circle has a new and shocking relevance.) A few summary executions notwithstanding, the torture is largely psychological- and yet the historical subjects are psychologically opaque.

“In Hungary, or at least in Hungarian culture, film nowadays plays the role of the avant-garde,” the venerable Marxist philosopher and critic Georg Lukacs told Yvette Biró, then editor of the Hungarian journal Filmkultura, in the course of a celebrated interview held in Lukacs’s shabby, book-crammed Budapest apartment during the glorious May of 1968. Lukacs had been particularly impressed by The Round-Up. Yet this laconic succession of fluid takes isolating tiny figures in the windswept nothingness of the puszta synthesized all that the philosopher repressed.

“If I can’t prove my identity, they’ll kill me,” one doomed prisoner complains. Beyond The Round–Up‘s veneer of chic existentialism, anathema to orthodox Marxists, Lukacs might have easily seen the “decadent modernism” of Kafka, Beckett, and Genet, not to mention obvious parallels to the nihilistic theater of the absurd. Instead, Lukacs discovered an imaginative representation of the circumstances under which he himself had lived his life-and, beyond that, the unmistakable (but also unspeakable) evocation of the unrepresentable 1956. The Round-Up‘s Hungarian title may be translated as “Hooligans,” the official term for those whom Time dubbed Freedom Fighters. And as these captive losers are imprisoned in open space, so the movie maps a particular state of being: “Do you accept this condition?” an Austrian officer asks a Hungarian detainee who, in order to save his own neck, is about to inform on his nephew. “Well, sir, I must,” is the reply.

-(1967).avi_snapshot_01.24.57_[2011.07.21_23.02.48].png)

The Red and the White

Jancsó futher developed The Round-Up‘s ceremonial cruelty in his next film, The Red and the White (67). Commissioned by and shot in the Soviet Union to mark the October Revolution’s golden anniversary, The Red and the White presented a brigade of Hungarian volunteers fighting for the Reds in the 1918 Civil War. The Red and the White was in production at the same time as Alexander Askoldov’s later-banned Civil War drama Commissar and, in contrast to Askoldov’s subversive revolutionary idealism, offered a remarkably perverse celebration of the proletarian internationale: wide screen and wildly aestheticized, the movie’s narrative and characterization are even more abstract than in The Round-Up, and all sense of the “fraternal” is turned on its head.

Civil War in The Red and the White is a chess game in which two armies battle back and forth, successively occupying the same indifferent landscape in a series of lethal, geometric reversals. The camera prowls through the action, catching sight of a marching formation or dodging back from a pair of wheeling horsemen. It was claimed that Jancsó first choreographed his showy camera maneuvers and then blocked the action to match; others reported that it was all improvisation and he directed the camera operator as the scene unfolded. (A colleague present on location wrote that “the camera [was] taking part in the gigantic confusion as a continuous observer.”)

Jancsó’s world is the totality of its laws—aesthetic and otherwise. He remains resolutely outside his characters, noting merely their wariness, vulnerability, and resignation in the face of death. As The Round-Up reminded some of Kafka, The Red and the White evokes the cruel beauty of Isaac Babel’s Red Cavalry. Few war films have been so little concerned with heroics and so fascinated by the logistics of killing. Although not shown with bloody verisimilitude, the disposal of prisoners is all the more horrifying for its matter-of-factness. (There’s a sense in which Jancsó is the European equivalent of Sam Peckinpah.) Captors take target practice on fleeing captives as they run naked through the fields or shoot their prisoners point blank and dump their bodies in the placid Volga that eddies through the verdant landscape.

Mass murder in bucolic summer: The Red and the White is something like an austerely pornographic pastoral. Midway through, Jancsó introduces a field hospital staffed by a gaggle of pretty wood (or water) nymphs. The Whites march them and a military band into the birch wood for some girl-on-girl waltzing. Then, in a further demonstration of their power, they compel the unwilling nurses to identify the Red patients in their care-as well they might.

.avi_snapshot_01.24.57_[2011.07.21_23.02.48].png)

The Red and the White

Such forced betrayals and denunciations notwithstanding, the movie’s back-and- forth action is programmatically difficult to follow. The Red and the White‘s built-in joke of having the Reds speak Hungarian while the Whites use Russian may have insured that the film would never be released, at least as Jancsó shot it, in the Soviet Union—although by the time the movie ends the distinction between the two sides is nearly moot.

Jancsó played out a similar dialectic in his next film, the glum chamber drama Silence and Cry (68). Here the conflict is contained within a single tormented family. The Hungarian Soviet Republic of 1919 has collapsed. A Red soldier seeks refuge in the countryside, and a White commandant (who may be his brother) orders a farmer’s family to hide him. The diminutive peasant, himself a former Red, is at once being punished by the authorities and poisoned by his wife. These sinister enigmas force the fugitive to blow his cover and shoot the commandant. Jancsó’s direction is characteristically terse-nothing is explained and the soundtrack is all but liquidated. It was here that Jancsó introduced a new editing pattern: each lengthy shot constituted an individual scene, and every cut marked either a spatial or temporal shift. This strategy would come to fruition the following year with his first color film, the French-Hungarian-Yugoslav co-production Winter Wind (69).

Capping the icy symmetry of his previous films, Winter Wind was composed of only 13 shots, some as long as ten minutes, and each a completely mapped-out sequence. These tracking shots are, in fact, the subject of the film, which ostensibly depicts the cell of Croatian fascists (Ustashi) who assassinated King Alexander of Yugoslavia on his 1934 visit to France—an incident that nearly triggered a Mitteleuropean war when it was revealed that the terrorists were trained in Hungary.

As usual, Jancsó’s interest is more geometric than geopolitical, eschewing the big picture for micro-social behavior. Opening with a newsreel of Alexander’s killing, Winter Wind purports to dramatize the intrigue that preceded it, “a mechanism that had gone mad,” per the filmmaker. As the terrorists plan the assassination, one of their leaders, a grim revolutionary ascetic named Marko (played by the film’s French producer Jacques Charrier), escapes a bungled ambush in Yugoslavia and crosses the border to the group’s Hungarian hideout.

Winter Wind

Despite Marko’s devout Catholicism, he’s far more an anarchist than a nationalist. And although he’s considered a national folk hero, there’s an utter absence of trust between him and the rest of the cell. Indeed, Marko refuses to take an oath to their organization. He’s a royal pain, and, when the Hungarian authorities let it be known they consider him too hot to harbor, his fellows gladly make him a martyr and are last seen pledging their allegiance to Croatia in his name. But this obvious irony is only a detail in a film that concentrates mainly on Marko’s not unjustified paranoia amid the group’s shifting patterns of loyalty.

“Don’t stand behind me,” Marko snaps at one of his supposed comrades, as much director as revolutionary. “How many of our men have you shot in these rooms?” Everyone’s motivations are ambiguous. The elaborate, oblique power struggles enlivened by a cheesy, barely motivated lesbian love affair between Marina Vlady and Eva Swann take on epic proportions as registered by a peripatetic camera pacing back and forth through the snowy landscape with the relentless deliberation of a caged animal. (The camera is less mobile when it ventures indoors but Jancsó maintains the beat with the amplified sound of boots treading the wooden floors.)

Appropriately, this coolly formalist exercise in political prurience and svelte sadomasochism was distributed in the U.S. by Grove Press. Making a note of it in his Village Voice column, Jonas Mekas seized upon it as evidence that there was avant-garde film east of Vienna.

The dance of the dialectic continued. Winter Wind was invited to Cannes in May 1968, but Jancsó was unable to screen the movie when student militants and their filmmaker allies closed the festival. Times had changed but the more things change . . .

Red Psalm

Jancsó’s next film, The Confrontation (69)—in which dancing, singing student Communists face off against Catholic youth in the brave new Hungary of 1947—would extend his fascination with group dynamics, while addressing the zealotry of the New Left. The director dressed his own generation at the zenith of its youthful idealism in the blue jeans and miniskirts of the Sixties.

Subsequent films were blatantly allegorical. Agnus Dei (70) made no pretense of naturalism in putting an assortment of peasants, soldiers, and priests through a symbolic reenactment of Hungary’s 1919 revolution and counterrevolution; the abstract folk musical Red Psalm (71) mixed Catholic liturgy and classical mythology to create a socialist passion play celebrating the “harvesting strikes” which swept rural Hungary in the 1890s.

For its first hour Red Psalm unfurls as sinuously as a strand from the maypole around which the peasants dance. The strikers are ultimately massacred by the army that has been circling around them throughout, but this attempt to recast history as ritual is Jancsó’s most optimistic film-perhaps the most ecstatic fusion of political and formal radicalism in the 40 years since Dovzhenko’s Earth. But optimism was not a Jancsó forte; writing its own epitaph, Red Psalm would also be the last.