By Kristin M. Jones in the January-February 2016 Issue

Review: Sixty Six

(Lewis Klahr, U.S., 2002-15)

Messages and portents bubble up throughout Lewis Klahr’s 90-minute, 12-episode feature Sixty Six, which poetically fuses images and ephemera of the Sixties with Greek mythology. It begins with the brief film “Mercury,” in which light-box-illuminated double-sided pages from Flash comics evoke the fleet-footed messenger god. A pulp serial that shimmers with potent emotions and fragmented memories, Sixty Six is made up of digital films Klahr began working on in 2002 and fittingly opens with an epigraph from Paul Eluard and André Breton: “Let the dreams you have forgotten equal the value of what you do not know.”

From the January-February 2016 Issue

Also in this issue

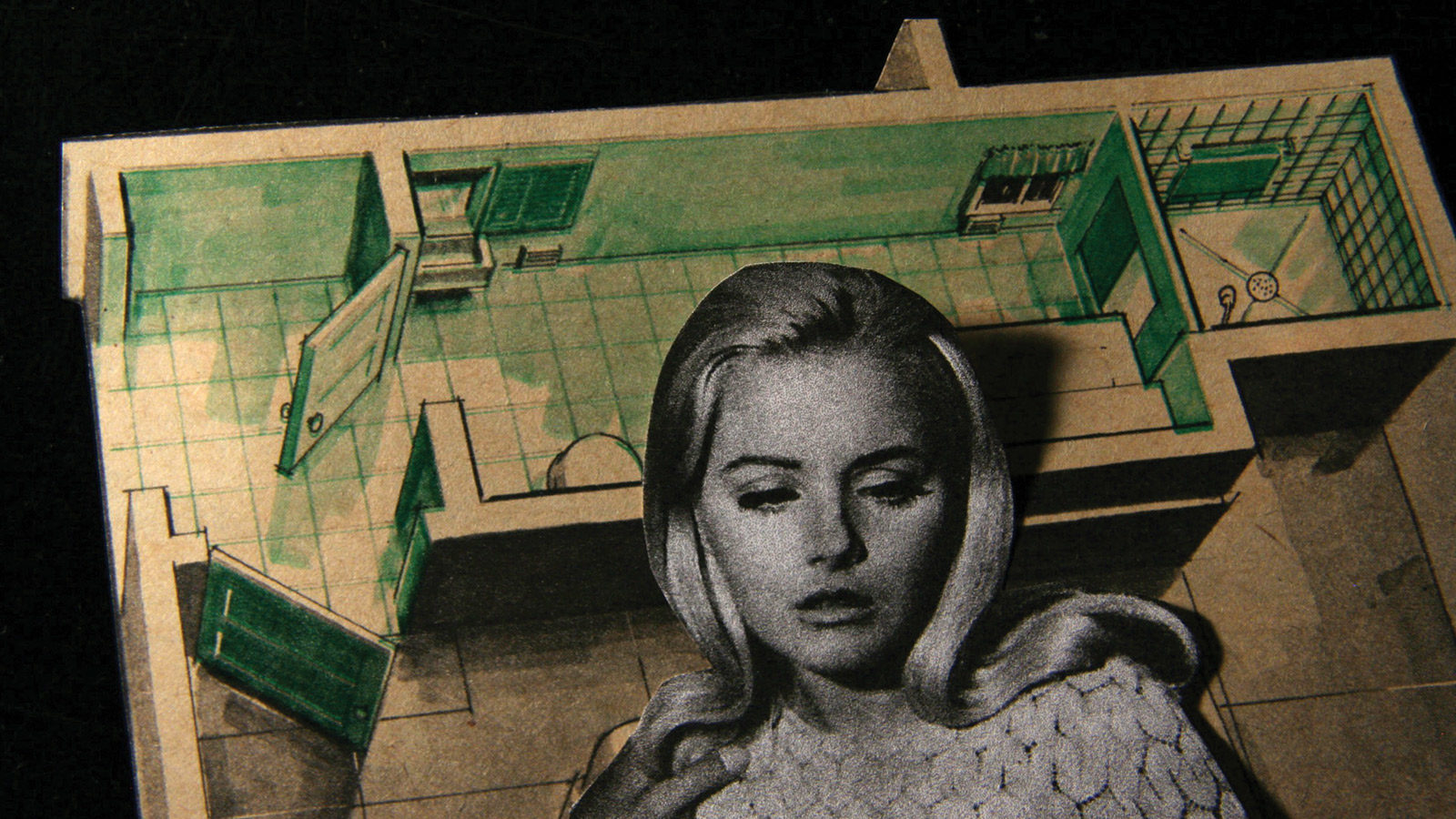

Typically appearing in black-and-white photographs shot in Los Angeles, sleek modernist architecture forms a cool dreamscape that undergirds the series and contrasts with collaged objects and images that are richly hued and often worn-looking and mysterious. That alluring utopian backdrop first appears in “Ichor” (whose title refers to an ethereal fluid flowing in the veins of the gods), in which a body is carried by a house, magnifying glasses materialize, and a female narrator makes oracular pronouncements such as “Even while you ask the question, the disease is undergoing a change.”

Later, in “The Silver Age,” the mood of daylight noir reemerges, but with more overt allusions to crime (a gun aimed at a house, open safes), as well as backwards love songs on the soundtrack. The penultimate segment, “Orphacles,” is again riddled with prophecies. It follows an irascible mythological figure conjured from Klahr’s imagination, and is marked by uncanny eruptions such as speech balloons containing only dark blotches.

Sixty Six

The number 66 evokes both an era and a cosmic road trip. In “Erigone’s Daughter,” a blonde made up of various cutout characters travels into a fraught past, set to a collage soundtrack of anxious dialogue from the Sixties television series Route 66. Images of car tires, pill capsules, anonymous bedrooms, suitcases, television screens, and greenery are redolent of asphalt and complicated emotions. The stained-glass-like “Mars Garden” follows, its moodily radiant double images echoing those in “Mercury.”

Time is subject to endless alchemical transformations. It metamorphoses into color in “Saturn’s Diary,” in which calendars, chiming clocks, and objects including coasters and bottle caps convey a god’s sparkling but not uncomplicated life in the opening months of 1966. Eventually, he vanishes, leaving silence and flickering colors. And in “August 19, 1966 (Jupiter Sends a Message),” Klahr resurrects memories of a long-ago Long Island summer through the sounds of crickets and thunder and scanned details of images from Life magazine—lush trees, a floral-printed mattress—that evoke humid days and nights.

Throughout Sixty Six, Klahr unleashes a dazzling array of visual ideas, deftly combined with sounds, silence, or music and all in the service of what he calls the film’s “pop associational mindscape.” In a heart-stopping moment later in “Helen of T,” a blonde, followed during her effervescent youth in New York City and as she poignantly ages, passes a poster reading “Art of the Sixties” and depicting an immortalized Roy Lichtenstein comic-book blonde. Where does life end and art begin? Color, especially, in charged dots, stripes, targets, and grids, summons an array of moods and situations.

Sixty Six

But color is almost absent from “Ambrosia”—a brief, astonishing, and entirely silent episode—until actual blossoms appear near its conclusion, overlaid on a black-and-white photograph. A cinematic still life, it scrutinizes a mid-century banquet, with its half-eaten meals, crumpled napkins, soda bottles, and glassware. Some revelers appear, but their faces are cropped out; instead, the visible texture of the paper on which the images were printed evokes sensual memories.

Even gods can sink into oblivion, while the traces of their appetites remain. Sixty Six concludes with the mournful and erotic “Lethe,” set to music by Gustav Mahler—an exquisite pulp sci-fi melodrama about desire, death, and rebirth. Lethe, the river in Hades from which dead souls drink water to forget earthly life, is just one of the powerful metaphors flowing through the haunting journeys in Sixty Six.