By Harlan Jacobson in the January-February 1988 Issue

Interview: Cher

The singer and actress dishes on Moonstruck and more in this 1988 interview

When I go up to her duplex in the Morgans on Madison Avenue, where she is staying until her New York co-op is renovated, I enter and gasp at the subdued decor. Everything here exudes boardroom conservatism: gray, black, white, more gray, and wood. “I thought you had trashy tastes,” escapes my mouth. I was expecting pink Lava-lites and a gold bust of Elvis in the hallway.

“Nope,” says Cher, the Vamp of Nirvana, as I trail her up, up, up a circular staircase with an ash bannister to the second floor. Blink. There’s a black couch grouping, a black shiny cube for a coffee table. The room opens to a solarium with a running track and a kind of satellite dish on a pole. The skyline twinkles.

“You want anything?,” she offers. I ask for scotch, and a guy—I swear he had wings—appears, poof!, with a bottle. This makes me nervous—the last thing anyone who spends time with her need be. Ironically, while she has had everything known to woman done to her—nose bobbed, teeth capped, back tattooed, Mack the Knife knows what else—the thing you notice up close, or even in performance from the back row, is how (just exactly like Dolly Parton under all that powder and ice) absolutely real she seems.

We go into her kitchen to talk while she makes spaghetti. She boils up the pasta, then takes out a carton of sauce she’s had sent up from Umberto’s Clam House downtown and dumps it on. Tastes. Grimaces: something’s missing. She goes back into the fridge, pulls out a bottle of Prego and dumps it on. Tastes: that’s better. We suck noodles.

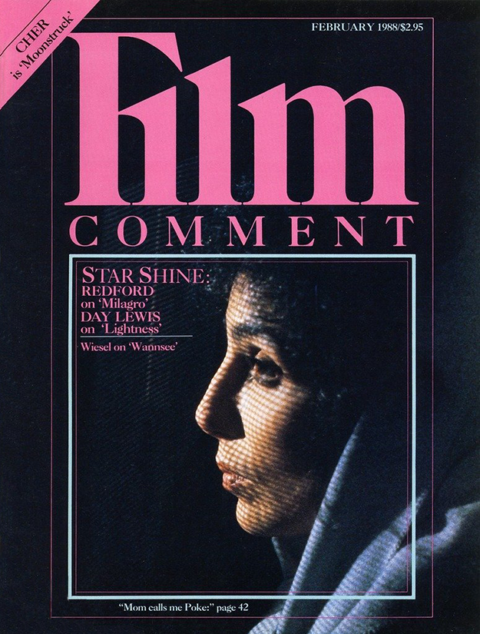

She sits in the fading sun of her aerie. She has on a gray sweater, black pants tucked pirate-style into black moccasin boots draped in diamonds. Her jet black hair is wild and frozen: it is Cher Medusa. She is, as each David Watkin shot in Norman Jewison’s Moonstruck glories, drop dead gorgeous.

Cher in Moonstruck (Norman Jewison, 1987)

If you want to understand what has happened to her since Sonny, you have only to understand who preceded her and didn’t make it. Remember Keely Smith? Who back in the ’50s rolled her eyes and made a point of boredom while her bantamweight cockatiel, Louis Prima, went bats on the horn? In retrospect, the Sonny & Cher Act is so close that were it not for the statute of limitations Sonny could get indicted for grand theft. Well, imagine lightning having struck Keely Smith, and you understand Cher.

She is not analytical. She does not depend upon those tools. She did not go to Bryn Mawr and get a masters in Art History. Instead, she became Cleopatra—much to her surprise—and Cleopatra knows how the world works, and how to work the world. She has taken charge of the barge.

Where she is least in control and at her best is in her acting. Her first record in years, with the exception of the reworked cut of Sonny’s “Bang Bang,” seems overwrought, over-produced, and mostly at the same gymnasium workout pitch. The titles of the cuts tell the trite story: “I Found Someone,” “We All Sleep Alone,” or “Perfection.” And if the titles don’t, the lyrics written for her insist upon it:

Hush little baby, gotta be strong

’Cause in this world we are born to fight

Be the best, prove them wrong

A winner’s work is never done

Reach the top, Number One

Perfection.

Oh, perfection

You drive me crazy with perfection

I’ve worn my pride as protection

Perfection….

And so on. But it half reveals why she rivets attention when she’s onscreen. Unlike singing, she hasn’t got the business by the throat. The camera loves her, and somewhere inside there—the person who is Cherilyn Sarkisian of rootless California—she may know the fear of wanting to trade up and being unmasked. She responds to her small potato characters with the emotional resonance she learned in the—you guessed it—School of Hard Knocks. No theory here.

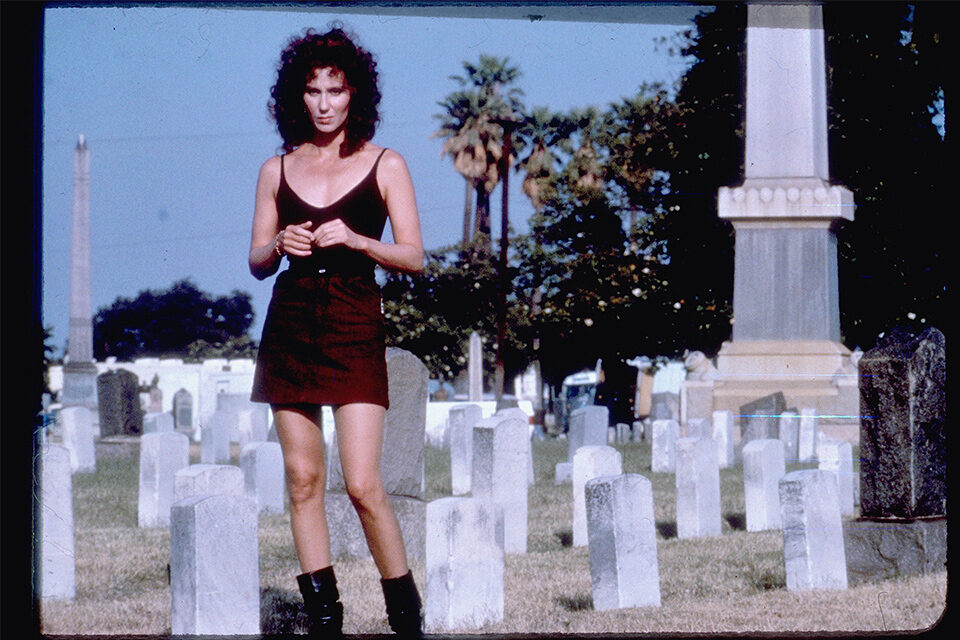

You couldn’t miss her return to the high school reunion in Robert Altman’s Come Back to the Five & Dime, Jimmy Dean; or as the lesbian friend of Karen Silkwood in Mike Nichols’ Silkwood; the biker mom with a bad drug habit who never runs out of the milk of human kindness for a deformed son in Peter Bogdanovich’s Mask; the lusty wench Alexandra Medford opposite that old devil Jack Nicholson in George Miller’s workup of John Updike’s The Witches of Eastwick; the mousey lawyer in Peter Yates’ forgettable Suspect; or especially as Loretta Castorini, the 37 year-old Brooklyn accountant who slips her ledger to become a lover at last in Norman Jewison’s Moonstruck.

Jewison, unfortunately, italicizes every little joke or nuance of character with a soundtrack that tells the audience what it’s supposed to feel: whimsy for an old Italian man, pathos for an abandoned wife, and so on. But whatever else it isn’t, Moonstruck may be a meltdown for all the men dragged out to see Cher at the Sixplex. The eyes drink her in. You want to be the guy with the wooden hand who gets to take off her glasses.

And so it is now that all the would-be Arthur Millers of the press have found their dream of the new Marilyn: a Valkyrie who can let the wind blow up from the grate of Hell to snatch their attention, but is down to earth. Like revenge, she eats Prego spaghetti sauce cold. The difference is, of course, 20 years of feminism have given her the arsenal Marilyn never had, have taught her that helplessness is not as wise a political position as “I’ll just help myself, pal.”

Inevitably, Cher has some canned responses. She mostly delivers on the dime, but remembers that I am press (”Honey,” she warns Main Man Rob Camilletti, downstairs, “don’t say anything. The press is here.” “Yeah, don’t say anything either,” he calls back). She has been burned before that very day, she feels, by a Newsweek cover story, and previously by a New York Times Magazine piece. The oddest thing is that throughout—as the sun goes down around us and the apartment gets dark—she responds with her hand over her mouth. Why, I wonder, but fail to ask.

Bobby Camilletti, look around. It may be gray, it may be temporary, but judging by the company alone (if not by the way the scotch showed up), you are in heaven now, buddy.

Cher and Nicholas Cage in Moonstruck (Norman Jewison, 1987)

Somebody said that they felt that I did lot of things that I do because I don’t want people to know who I am; and in a way, it’s true. You can’t trust people with your feelings, you can’t trust total strangers with your emotions; you can hardly trust people you love, so I don’t want everybody knowing every vulnerable part about me.

You say you don’t like interviews like Newsweek. What do you get asked?

First of all people don’t ask much. You sit with someone for hours and what they get out of it is that I spend a lot of money on clothes, and my boyfriends are young, and I changed careers, and I dress weird. Well, if that’s all you want I could give you that in five minutes, and we don’t have to waste each other’s time.

But you do it all the time.

I’ll tell you something, if I had the luxury of not doing it, I would never talk to another reporter, journalist, whatever for the rest of my life. You can’t know me. I mean people that I’ve lived with can’t know me; my mother doesn’t know me, you know?

Especially her.

Well, not especially my mother. My mother knows one side of me, my children know one side of me. Boyfriends know one side of you. The boy that I live with now knows me better than anybody that I’ve ever been with. It’s because I trust him more than anyone I’ve ever been with.

Why?

Because he’s trustworthy and his morals are just impeccable. That’s another thing that pisses me off, when people just dismiss him as a bagel maker—what’s wrong with that? The press likes captions to fit under a picture, or snappy little one-liners in bold type. I’ve been doing it long enough it shouldn’t bother me, and yet somehow it still does. I don’t care if people like or dislike my views on things, if they could just get it accurately, that would be a bonus.

Do you feel insulted when they call him a bagel maker?

No, not at all, because he was a great bagel maker. Do I feel insulted when they dismiss everything about him and boil it down to that, without a moment’s thought to what kind of a human being he is? Yes. I lived with him when he was a doorman, when he was a bartender. I don’t really care what he is.

I’m not asking about him, I’m asking about you.

I didn’t think that what people said about Robert as applying to me in an earlier stage. You know, it’s been such a long time since I was anything other than what I am that I don’t think about it that way.

I go out of my way to try and do women who are heroic people that would never make the cover of any magazine. You might find them in People, or somebody might know about them. Like the woman I played in Mask was just a total loser, and yet she did one thing perfectly, and that was she mothered this child that a lot of Betty Crocker-Betty Furness mothers might never have had the guts to do. I don’t find playing people like myself that interesting. That’s why I don’t hang out too much with the A-crowd or whatever.

Do you think of yourself as working class?

Absolutely. My children are rich children. I’m not.

When you say that they’re rich, does that mean they think that stuff is just supposed to come?

My son has a little bit of that attitude, but we’re trying to break him of it. He’s only eleven, so maybe he’ll have a lot more going for him soon. Right now he’s a little superficial.

My daughter is very Anti. It’s really weird. She dresses like a bum. Doesn’t want new clothes, goes around real piggy, doesn’t care about my trappings—says they’re things she’s totally opposed to. And yet she wants our maid to come to her at NYU and wash her clothes and all that. So, she’s got a lot to learn about the real deal.

But she’s not superficial—she’s just young, just sorting herself out. She’s a lot cooler at her age than I was. She knows that the work is interesting and the business is shit.

Tell me.

I have a friend who’s an actress, a really fine actress, and we were talking the other day. And she said, “I love my work and I hate this business.” And she says it’s so difficult; but we all know what it is. It’s not like it takes getting into it to know what it is; and some people are luckier. Like Jessica Lange.

No one’s going to fuck with her because she doesn’t really give them a chance and she’s quiet in her rebellious nature. I’m much more obvious about it. She’s gotten so far away from King Kong, and somehow my King Kong is always right behind my shoulder.

What do you mean?

I mean my trashy part. I continue to do really stupid things—like dress the way I dressed at the Academy Awards…

Do you think that was stupid?

No, I thought it was great.

Me too.

But as far as winning friends and influencing people, it’s stupid. But that’s just always going to be me, it’s going to be the way I do stuff because I just have a hard time with authority.

If it costs you an Oscar, are you prepared to live with it?

Yes. I don’t think I could have said that before but I can truly say it now. It’s not the most meaningful thing in the world. It would be nice; it would be a bonus; and if not, as long as I can keep doing the work, that’s what’s important.

And also, I know that the people who vote on the best actors and actresses never even have to go and see the movie. A lot of it’s about a popularity contest.

Is that what you were afraid of that night?

You know what I really thought? I didn’t want to go; I was really hurt. I felt [the Academy] pulled a woman out of another category, and didn’t recognize me, I can’t believe that. And I was really hurt, and I know all the talk: they don’t like the way I dress, they don’t like my choice in men, they think I’m too flamboyant, they don’t think I’m serious. So then I decided I could go in a little black dress. And then I thought, well, fuck it, let me go and remind them what it was that they truly don’t like about me.

I thought, well, fuck it, I’ll go this way. I was really scared too, to go, and Stanley [Donen, the Awards’ producer] said, “Cher, come on do it, you belong here as much as anybody else.” And in the middle of the ceremonies, I just said to Joshua [Donen], “I’m having such a great time; I don’t care if I wasn’t nominated; I’m having a fabulous time.” But it was only that I could go, and be who I was, and let them do whatever they want to do with who I was.

Cher and Nicholas Cage in Moonstruck (Norman Jewison, 1987)

Eventually things come around your way. Suddenly, you’ve got the press saying, “She’s really serious after all, this isn’t just a trashy vamp…”

There’ve been lots of trashy vamps who’ve been really good actresses. I mean there’s been lots of trashy people. Marilyn Monroe was a great actress; she was a real trashy woman… How about Mae West? How about Heddy Lamar? How about Ava Gardner? How about all kinds of actresses who lived a life that makes me look like fucking Mary Poppins, you know?

Or women today who are much more trashy, whatever that means: they go with more men, or do drugs, or drink a lot, or live really in the fast lane, but they look right. It’s the problem with our whole fucking society. Nixon looks right, you know? That guy, Bakker, he looked right. Ronald Reagan looks right, but what has that got to do with anything? I could look right if that’s all it was about. I know how to dress, you know? Like a Mom, if I want to; but I don’t know what it has to do with who I am, or what my acting skills are, or whether I can sing or not, or…

But your image is pretty edgy and edge reminds people how tightly they’re holding on.

I think that it’s a little bit nervewracking for me in a way. In Mask there was lots of innuendo—it was more about a way that she walked or stood, or how she presented herself. There was one bedroom scene that got cut out. And I remember having to kiss Dennis in Suspect, because they felt that the audience would feel cheated if I didn’t.

And in Moonstruck, the sex is more like a caricature, so it wasn’t hard to do. The scene [when Cage beds her] was so funny that it wasn’t really about sex. When I was doing it, I just thought, “How’m I going to remember all these words?”

In Silkwood there was nothing. In Jimmy Dean there was nothing. I always admire people like Kathleen Turner who can just kind of kiss or take her clothes off or whatever. I have a problem with that. It just doesn’t seem to come as easily to me as other things do in acting.

Cher in Mask (Peter Bogdanovich, 1985)

Her roles onscreen are about sex. Your roles onscreen actually are not about sex . Your persona offscreen is about sex. It’s about being a bad girl. And that becomes threatening. It says: Hey, I’m taking over here.

Yeah. It’s strange though that it has to come down to that. I read a lot of scripts that don’t do anything for me at all, period. But it’s not like there’s a formula and if all these things add up, well, then I’ll do it. I guess if there was a real love story… I just don’t want to do movies about sex, though.

You know, I’m serious when I work. I’m not a “serious actress.” I think “serious actress” is a real stupid term. I mean, how can you not be serious about what you’re doing when you’re doing it? I’m not going to be pigeonholed. You know, I waited too long to get here. I’m dead serious about my work.

Okay. A lot of your career—not just your career—your life has been about getting control…

Yeah. Because, you know what? I gave it up to Sonny when I met him. I was 16 years old and I really didn’t know my ass from first base, and he really took care of me. I was real sick when I met him; I’d had hepatitis for a long time. I was floundering. I’d moved out; I thought I could take care of myself. I couldn’t. And then when I left him—I was with him from 16 to 27—I didn’t have the skills that a person needed, really, to take care of themselves in any fashion, careerwise, any kind of way, you know. I think I learned how to make out a check when I was 27. I never travelled alone, all kinds of weird things. I had to start from scratch and I made lots and lots of mistakes.

And I think mistakes are as good as successes, we just don’t see it that way.

Were you scared of failure during the period before you went into acting?

How do you mean?

That you’d get lost? That you’d eventually be the opening night lounge act in Atlantic City in ten years…

Yeah, that’s why I just had to stop what I was doing and go do this. I mean, you can call yourself a brain surgeon but unless you’re doing surgery it doesn’t mean shit. Staying in Vegas was very easy because there was so much money involved, and you didn’t need a brain to do the work—and it wasn’t horrible. But I didn’t make that much money…

$350 thousand a week…

I made a huge gross but I needed a whole bunch of people around me onstage because I didn’t really like what I was doing. And I thought, if I don’t change now, it’s always going to be this way. This is going to be it for me; this is going to be it. I’m just going to end up like ah—I don’t even know. I’ve said Dinah Shore, but I think it’s unkind, you know? Because Dinah Shore was popular for something before I was grown up, but I never really knew what she did; and I was afraid that was going to happen to me.

So I just said, “Oh, fuck it, if I can’t be an actress because I’m a singer, I just won’t be a singer. And we’ll see what happens.”

Are you nervous acting, when you’re trying to be somebody you’re not?

Well, like in Moonstruck I was a little bit nervous because I thought this woman accountant has to be really precise and if she’s not, it’s just going to be a joke. There was no risk in Witches, because it wasn’t much of a part. And I loved doing Mask so much that it didn’t make any difference, I just knew I was right for it. And nobody else wanted it.

How about Suspect?

Well, I thought it was going to be something that it didn’t turn out to be…

It wasn’t you.

There was definitely me in there but you never got a chance to see it.

Where was you?

Well, me was in some close-ups and me was in some scenes that never came about.

You mean the sex scene.

No. I took that out because I really felt that it was inappropriate. I didn’t like it in Jagged Edge and I didn’t want to be a part of it in this movie. And also after I met these women [lawyers], I realized how inappropriate it would be. There was so much more to this movie than what we got out of it. It was a really beautiful script.

How did you feel about the Quaid character coming up with key things that you had overlooked that were crucial to the homeless man’s [Liam Neeson] fate? In other words, giving you legs and him a brain.

Well, unfortunately in the original script, this woman had a case load that would choke a fucking horse and no support. She’s up to her ass in not just Liam but 40 other people. But Peter [Yates] decided not to leave this in the beginning, and we had the hugest fight. I begged him to at least leave a scene with this guy who had raped a woman—and it was a great scene—so you see that she’s overwhelmed.

Because then the tilt becomes somebody who’s overworked instead of inadequate.

Yes. How about that one? That’s what the whole movie was about, not about a woman who was stupid but who was so over her head with work that she was fucking up.

Is that the part that you thought was you?

Well, I thought that I did a good job showing a woman who could have done a good job but had everything working against her. But what Peter decided was important really wasn’t that important to me.

Like what?

Like when she’s trying to talk to him [Liam], and he’s scratching something into the table and not paying that much attention to her. And then she sits down, and she’s really frustrated, and sees he’s scratched her name into the table. And when I read that I cried because I thought this guy, who was biting everybody’s hand, is now reaching out to this woman because he knows she cares. I spent time with these women, they don’t have a fucking life. They kill themselves doing this, and I felt that we didn’t show any of that.

But it was a good working experience. I liked everybody I worked with, you know, you’ve got to learn from everything you do. It can’t all be perfect. Life isn’t about perfection…

Well, okay, after Suspect. you said that everyone in the picture was homeless. And that’s the definition of having no control…

I don’t know why this whole thing about control. I mean, I don’t have that much control over anything.

And I’m not striving to control everything. I try and control the things that I can control. I’m working in a business—in Hollywood, you know, and there’s not that much control to be had, truthfully. I can only control what I can control.

Do you want to be like Streisand and Lange, who try to get hold of a production?

I have a production company. And I’m trying to do good work with it, you know, trying to find projects that I think are really good. But I have to be able to control my own work, as much as I can control it. Look I controlled my own work as much as I could in Suspect, and when it came out it wasn’t very representative. So there’s not a lot of control to be had.

Let me harp some more on control. I want to keep beating on it. Okay?

I don’t care. Fine.

Cher, Susan Sarandon, Michelle Pfeiffer, and Jack Nicholson in The Witches of Eastwick (George Miller, 1987)

In Mask you take care of and give tools to a damaged kid, but more to the point, who is different than we are.

I think that’s something that all women fear. But I don’t know how far to go with that. You know how difficult life is, anyway, and you don’t want your children to have to go through something more than that.

My son was born tongue-tied and I watched them give him this operation. And they asked me to leave the room, and I said, “You haven’t got a snowflake’s chance in hell. If you’re going to cut his tongue apart, I’m going to stand there and watch it.” And I remembered thinking while I was watching, “Oh, I wish this didn’t have to happen to him.” And I know that that’s what Ricky’s mother [in Mask] thought about her child: Oh, I wish this didn’t have to happen to him. And yet she made the best out of it and she made him a great human being.

So, we should all have control over what we can, because there’s so little control to be had. If you can control something, why not? I don’t think it’s a nasty thing. I don’t think it’s a bad thing. It’s like the Church on being selfish: they’re against it because then it’s easier for them to control you.

I don’t think it’s a bad thing either. And, understand, I’m not trying to get you.

No, I don’t care. I mean, I’m going to tell you what I feel, no matter what you’re going to do with the information. But you know, everything makes me seem like the fucking control freak. It’s not about that. I’ve been told “No” so much—truly—that if I didn’t say “No way,” I’d still be doing nothing. I would still be in Las Vegas. I won’t believe that no is a no.

Okay, for women now it’s almost a political necessity. And your roles are about that, and your clothes are about that—although in a very traditional way: it’s only the first tool. It’s “I can get your attention.”

But if you ask my mother, I started doing that when I was about four years old.

But that’s what we teach little girls real early: if you want power, become an object.

True.

So what your clothes are saying is, ‘Okay, I’ll play the object game—now, fuck you, because I can go beyond that.’

I believe that. But you certainly can’t say fuck you unless you can back it up with something. Barbra Streisand certainly can’t say fuck you with her face or her body. she’s got to say fuck you with her voice and her talent. Marilyn Monroe could say fuck you with her face and her body and she could also say fuck you with her talent.

But she ended up…

I know, but I mean this is a business that eats its young, you know.

You said that before.

Yeah, but it’s true. It’s not a business that perpetuates good values. I worked on Witches with Jack Nicholson and Susan Sarandon and Michelle Pfeiffer, and everyone of the cast and crew really cared about each other and wouldn’t back bite or do anything mean at all; and we had a producer who saw none of us as human beings, not even Jack. Which really blew me away…

Who was that?

Jon Peters. And we had a director [George Miller] who was just totally unaware that we were there. Now, for me, I didn’t really give a shit about that part of it; but it was like a scene out of Tootsie: Everybody was somebody, Jack was Jack, and we were “the girls.” They treated us like shit. If we wanted something we had to go to Jack, cause none of us were the kind of women that would go up and go “Baby, baby, goo-gee-goo-gee, please give me something,” so we would go to Jack, and say, “Jack, you know, please help us.” But at least we went to a man who feels that women are smarter and better than men. But it’s not a business yet about women.

And even the women won’t help you sometimes. I’m amazed. I have a friend, Dawn Steel [now Columbia head of production], who I really love. But I guess she’s really tough and people don’t like her. But when women executives just have no regard for your feelings you go, “Well, you expect this from a man but you don’t expect this from a woman.” And I’ve also worked for people like Mike Nichols who has regard for you as a human being and believes that’s the way to get the best out of you. That’s why I was really upset about Newsweek where it said I caused problems on Silkwood. That’s bullshit. Nobody makes changes in a Mike Nichols movie that he doesn’t want.

I have been difficult. But I’m not a difficult actress; I’m not a difficult person. I really enjoy working with people and if you tell me to do something that I can’t do, something happens and I can’t do it. I just can’t do it. Not that I won’t try other things, but if you ask me to do something that I don’t believe in, then you might as well fire me. ‘Cause I can’t do what I don’t believe in; that’s why I don’t take lots of movies.

It’s like Peter [Bogdanovich]. I understood what Peter wanted and I understood why he was angry, and a lot of it had to do with the fact that I wouldn’t fuck him, too. Okay?

Really? How much of a problem was that?

It’s the only problem I’ve had. That’s the only time that that’s happened. It was a little earlyish in my career. I mean I’d already been famous my whole life but it was earlyish in my acting career. And the way he said it was, you know, “You think I want to fuck you but I don’t.” That was like at 7:30 one morning, while he was eating a fried egg sandwich. I mean, I was totally unprepared for it.

The fact of the matter was that I loved this woman [the mother] and these people, and he did not. And if you look at the rest of his movie you’ll see that Eric [Stolz, who played the son] and I are better than the rest of his movie. Because Peter didn’t understand them, because he didn’t like them.

And it’s not like I just go around storming down everybody’s walls. Out loud I said to myself one day, “What the fuck are you doing? You know nothing. You respect his other movies, you don’t understand what’s happening with him now.” Because this whole Dorothy Stratton thing was permeating everything. Before he let me do the movie he made me read the book of him and Dorothy Stratton. And I kept saying, “Where are you getting the balls to tell him that you can’t do it his way?” And all I kept thinking was “I really like this woman, I really know this woman, I really love this boy, I really love these people, and if I’m shit up on that screen no one’s going to say Peter Bogdanovich is a bad director.”

I think if you talk to Norman [Jewison], I think that what you’ll find is that I’m strong; but what good is there in hiring someone who’s weak? I just had an offer to play opposite Robert DeNiro in a man’s part because they couldn’t find anybody strong enough to stand up to him. I said, “I don’t know if I should take this as a compliment or if I should be insulted.” Anyway I explained to the producer why I was not the right choice and talked myself out of a part.

I’m not going to go around explaining to people what a good person I am because I think it’s totally full of shit. But I’m not this person that everybody thinks I am. I do frivolous things that are totally full of shit. I spend too much money on clothes, I’m really worried about my appearance, you know, but…

Do you know why you spend so much money?

Because when I was young I never had any clothes and I went to school with rubber bands wrapped around my shoes to keep the soles on. And because, until I became an actress, I never felt like an artist. I never felt like I was worthwhile. I always knew that there was something not right, that I was—I was famous, but it wasn’t right. It wasn’t what I had thought from the time I was little. It was just not right. I couldn’t trade off one for the other, because the only way I’d gotten people to look at me was creating this person.

There’s a song on your album…

“Perfection”?

Yeah, nobody paid any attention to it.

I know.

I underlined it like crazy in the cab, on the way over, because obviously it was written for you, and about you. You sing it, and you know what you’re singing.

Sure. I was thinking about exactly the same thing, today. You could reveal yourself from now to Doomsday, people are not interested in who you are.

So tell me about “Perfection.”

Well, obviously, it was written about me: “I’ve worn my pride as protection.” That certainly is a perfect line. It’s so funny because I’ve never thought about this song as much as I’ve thought about it today. I was doing the cover of Cosmopolitan, which is another thing that I wish I didn’t have to do, because I don’t like the magazine.

Cher and Olympia Dukakis in Moonstruck (Norman Jewison, 1987)

Why this incredible push? You make three pictures back to back, you don’t let yourself alone, you’re working like a maniac promoting. And promoting is the whore end of the business and nobody likes it. Why? Is this perfection?

I want to be able to continue to do this work, because I really like acting a lot. I didn’t really realize until the writer from The New York Times said to me, “You know, you’re either going to be made or broken this year.”

What?

And I said, you mean if these movies are both bombs I’m never going to work again? He said, “Well, you must have thought about that?” I said, “No, I didn’t really think about it.” I just thought I had a chance to do some good movies and I wanted to do them and there they were… And I didn’t think about it. But when he said that, it really scared the shit out of me and I thought, well, fuck, okay, does this mean that it’s true just because he said it? It can’t possibly be true.

You know what I was devastated about more than anything in his article? That I thought he was a nice guy and I was wrong. He was so much fun and so nice, and we had such a good time. And the most that I could think of was that he’s not very talented.

I never dodged a question—and when he said he didn’t know if I was telling the truth or not, it really pissed me off. Also he dismissed Sonny by saying he wrote gimmick songs in the ’60s. It’s like calling Robert a bagel maker. You can’t dismiss people like that.

The line that was a laugh-out-loud dead give-away was after he has given Robert’s age he says, “Chastity and Robert come into the house, Robert has been to the hobby store where he has bought a kite.”

It was a cheap shot, yeah. Robert made me this kite for our anniversary, and it was six feet by six feet and took him two weeks to make, and it’s this ship, a masted schooner, a four-masted schooner. And the guy could dismiss it by calling it a kite.

It’s like you’re his Mommy.

Yeah, so I was really angry about that. You can paint a picture with words to make anybody look any way you want to. It was the Reader’s Digest version of what Robert had done. People just don’t have what it takes to write in-depth articles about human beings. Because people don’t read. Look, I love America, but I’m very disappointed in what’s going on.

What do you mean?

We don’t read. We don’t care about who’s running our country, we don’t care about our neighbors. We don’t care about anything. We’re so interested in ourselves we don’t remember why this country started. What it means. Nobody can read, nobody can write. Everybody watches Wheel of Fortune. And I perpetuated that for a long time. I am a victim and a perpetuator of that.

I think if you look at Moonstruck, it’s a different set of values. And if everybody was like that maybe we would still be able to unlock our doors or not have, you know, some ass hole push a pregnant woman under a subway. Or that people might care if they have to step over someone who’s frozen in a doorway.

I think that’s one thing that’s kind of a thread in my characters: they’re all very old fashioned in their morals.

Nicholas Cage in Moonstruck (Norman Jewison, 1987)

When I saw Moonstruck, I thought you were wonderful, and that whoever did the camera…

David Watkin. What’s interesting about David, when he lights, he goes to sleep. He comes in, lights the scene, then he goes and takes a nap—after he’s done it, he’s done it.

I read someplace that I said it wasn’t fun to work with Nicholas [Cage], which is the truth. Nicholas is a very strange actor, he works alone and you get to work along side of him, but he’s very interesting to work with, he’s fascinating.

Did you like working with Norman [Jewison]?

Yeah, I did. He’s a very strange man. Very theatrical, he’s got lots of stories, he wants to be the center of attention, but he lets you alone. He’s real used to yelling but he’s not used to having someone yell back, and when you do, it becomes fun for him. Also, I’ve never known a director who, if you’re doing something funny in a scene, starts laughing. He laughed all the time when we were working, and I just… I just found that to be so bizarre, that he would just laugh. And you’d be shooting and he’d laugh.

Well, in Moonstruck you get to be both the bad girl and the good girl on the same dime. You have to do something that…

Is wrong.

Looks ugly, but the dice are really loaded, because there’s no way that Danny Aiello is the right guy for you. The audience is implicitly meant to resist: Hey, we’re giving a virgin to the cowardly lion here, folks. This is not good; let’s give her to Cage. So it’s loaded, and it’s in service to monogamy, to marriage, the family. It allows you to be both bad girl and good girl at the same time.

I don’t know whether you analyze or whether you intuit, but the parts you choose are real smart.

I think I intuit; that’s how I do everything basically. My mind doesn’t work nearly as well as my instincts, and even if they don’t, you have to cut it down the middle: You just can’t do everything you want. And yet you can’t sell yourself. I sat for two years between Mask and Witches, and I didn’t like Witches, but I took it because of Jack.

But you seem embarrassed by it.

Well, it’s no part for me, really. It’s not a part for anybody, it’s just an okay piece of fluff…

You’ve said that in 500 places; why are you putting distance between you and that movie?

Well, because I don’t feel so much a part of it.

Why not just say, fuck it, I did it?

Well, all right. That’s basically the way I feel—fuck it, I did it. But my whole life I’ve made lots of compromises. And in my movie life I want to know why I do things. And in my movie life I don’t want to make money compromises. I don’t want to make political compromises. When I took that movie it was a compromise. I didn’t love the character. All the other movies I’ve done, I’ve loved the characters.

I wanted a chance to work with Jack, because I’d almost worked with him once before and gotten totally messed up…

Okay. What was working with Jack like?

I didn’t see any big revelation I could use. Something religious didn’t happen to me, you know? It was Witches, not Ironweed. But working with Jack was worth everything. I’ve known Jack almost all my life and I’ve never known him until I worked with him—he’s brilliant, and it was fun to be around him. It gave me insights about him I would never know…

How did he appear to you?

He just appeared… so… loving and so… perfect in the strangest way. With all of his bizarre quirks and faults, he is a man who really loves women… I don’t know lots of men who really love women and who are intrigued and fascinated in a strange way by women and who feel really comfortable sitting in the trailer.

He gives a lot of himself. He told us stories about when he was young—and he certainly had a strange life—about when he first found out… that his mother was his aunt and his grandmother was, you know, that whole story where his mother—who he thought was his mother—was his grandmother and his sister was really his mother. And he told us, you know, when he found it out. Just great stories; he gives so much of who he is. And we had a hard time on this movie; when I say “It was a nightmare,” and that’s all they print…

What do you mean nightmare?

On my 40th birthday I got a call from George Miller, who says, “Unfortunately, Jack doesn’t want to work with you because you’re not attractive.” And they’re bringing in a cake and I’m crying. And before we started the movie, George Miller said, “I don’t want Cher ruining my movie.” And I had to go through this every single fucking day.

And there was all this talk about “pussy power” coming from the production office, and they lied to me and told me that Susan Sarandon didn’t care which part she took, and when we got together she wouldn’t talk to me for the first two weeks because I took her part.

And when I say Hollywood eats its young—I heard it from somebody else, but I live it—it’s not without some kind of foundation. They didn’t care that they killed Susan and really hurt her and took her part. They didn’t care that when they brought Michelle in to read for her part, they asked her if she would stick around and read my part. And Michelle said, in the middle of this, she realized that she was helping other women to test for her part-and she was already told she had it. These are the kind of things that make you tough.

Is it the dealing that bothers you?

I don’t really know that much about the deal part—that’s how out of control I am. I didn’t realize how savvy you’ve got to be to make sure you’ve got a decent trailer. You’d think that if you’re going to do a job, and they’re going to pay you over $1 million that they’re not going to scrimp on the trailer, or that they’re not going to fuck you around. Or say, “Well, when the movie’s over we’re going to show it to Jack and everybody, and if you girls are good you might get to see it too.”

That really happened?

No, that was an actual statement…

Those words?

Yeah. “And if you girls are good you might get to see it too.” One thing that I won’t do is lie about anything. If I don’t think something’s any of your business, I’ll tell you that, but I’m not going to lie. What I’m telling you is not something that I’m making up. And you don’t have to make this shit up.

But when I worked with Mike Nichols, everyone was treated exactly like they were Meryl Streep. And I didn’t know my ass from a hole in the ground. They had to keep telling me, “Cher, you’re not in key light. “ I didn’t know what it was. I still don’t know what downstage is, or what camera right is. I know it’s the opposite of what I think it is. Okay? But I’ve seen enough to know that there are really good people in this business and really bad people, and I haven’t seen the middle ground. I’ve only seen the two extremes.

And I know that you’ve got to play some sort of a game except that I’m not into it. All I hope is that I’m good enough that people will want to work with me. I don’t like the idea, though, that I’m difficult to work with, because I’m not.

That’s a real bind, because actually you are, but for the right reasons.

I don’t want to get in anybody’s way, I don’t play any tricks with actors. If you can take the scene from me, you’re welcome to it. I learned something from Meryl that if you work harder in my closeup than in your own, and I do the same thing, what we have is a great piece of work. It worked well with Eric [Stolz]. It hasn’t really worked that well since, but I don’t need to be the center of the universe.

How’s that square with “Perfection”?

Not the same. When I work, I work really hard. But I really prefer working collaboratively, because working alone is really difficult. In some ways I’m really childish; I’d rather make a game out of it because it’s the way I started when I was young, making up stories and stuff like that. Working on Silkwood was more like a game. Same with Mask and Moonstruck. I don’t like work when it’s just work.

Cher and Jack Nicholson in The Witches of Eastwick (George Miller, 1987)

Who else have you thought about working with?

Well, I had a meeting with Stephen Frears.

A friend of mine interviewed him, and when she met him in the Algonquin hotel he was scanning Women’s Wear Daily’s “Who’s In” and “Who’s Out” lists. And when he reads that he’s “In,” he turns to her and asks, “Who ya gotta fuck to get on the ‘Out List?’”

That’s pretty him.

What did you think of him?

I liked him a lot. “I took this meeting under false pretenses,” he said. “I don’t want to make this particular movie with you because I think I’m the wrong director. I just wanted to meet you.” I said, “Okay, that’s good enough for me. If you don’t want to direct this movie, I don’t want you to.”

Which movie?

It’s a movie that I have called Rain or Shine. So we just had a nice talk, and the guy who runs my company was having a heart attack wanting me to talk Frears into it. But people shouldn’t be talked into art, they should want to do it.

I didn’t see Sammy and Rosie—what did you think of it?

Oh, I loved it. I thought it was at the edge of where relationships are when two people are independent. Like in Silkwood, where your role was really tailormade for you. A sexual outcast in love with a political one. It perfectly captured a lot of who you are, a class outcast, and you’re aware of it…

Yeah. The interesting thing about it was not that she’s a lesbian but that she was just a woman. When Mike asked me about doing it, I said, “Sure, fine, whatever.” I didn’t care. I didn’t read the script. I thought, if Mike Nichols and Meryl Streep are doing it, how bad can it be? And I’m not getting any offers anyway, so this is perfect.

And then he called me a couple of weeks later and said, “Oh, I just wanted to tell you, she’s just really this adorable lesbian and bullshit, bullshit, bullshit.” And I said, “Okay, great.” And the only thing that you ever hear her say is, “I love you. Karen, I love you.”

There’s a wonderful scene on the porch.

Yeah, but that has nothing to do with it—I never locked onto the lesbianism.

If women could really be who they are—I was having this conversation with my friend the other day and she was telling me that she’s having a really good relationship with a man that’s starting to kind of turn into love; and in the beginning, because she wasn’t physically attracted to him, it was great. And I said, “Do you know why? Because you always pretend to be someone you’re not if you want to fuck somebody. You get this cutesy little girl quality going, and you act the way you think the person wants you to act. And what this guy has seen in you is the real you, and he really likes it because you’re just who you are the way you are with me.”

And if women were ever truthful enough with men to try not to bullshit them because they wanted to be liked by them, men would have a much richer experience with women than they get to have now.

You can bullshit yourself but inside someplace you know something is not exactly right. We’re nervous. Men and women are nervous around each other because there’s not a lot of truth happening now—out of fear of not being likable. Or: it won’t be good; it won’t work out; you won’t be sexy; you won’t be all the things you’re supposed to be.

You could be Nice, but Nice is not only what men want, because we’re split: we marry Nice and stick’ em out in New Rochelle but then look for Not Nice.

Why wouldn’t you want someone with as much energy and intelligence and as much going for them as you could get? And if you say No, how could that not be not nice?

Are you asking me?

No, I’m just, you know, I’m just musing. I don’t know why people don’t think that a woman who has a mind of her own wouldn’t be much more safe, and secure, and interesting, and right to be with, than a woman who would just do this and all that. When I lived with Sonny I was very uninteresting because I just did what he wanted. And I thought that’s what being a good wife was. Making him happy and doing what he wanted. And then I realized that I hated it.

Sam Elliott, Cher, and Peter Bogdanovich on the set of Mask (Peter Bogdanovich, 1985)

In your checkered career, you went out with a lot of powerful guys. Do you think they wanted to own you?

Oh, after Sonny, I think that the people I went out with were a lot more in tune to what’s happening now. But someone who has power-power is such a strange word—who has a certain amount of energy can get more of a sense of who they are by being with you. Now, it would be impossible for anybody to try to own me since Sonny, because I did it long enough to figure out that’s not what I wanted any more. It’s too complicated to break it down into that simple a thing. I don’t get the feeling I knew all the men pretty well, interestingly enough, but in one way I knew them better than Sonny, because there was a lot more communication with them.

With Sonny I just kind of hid everything I felt, because none of it was what he wanted to hear.

You lasted longer with him than anyone. I read that your relationships now go about two years, right? But still one at a time.

Well, I don’t like dating…

Nobody does.

And I like being with one person. A lot of times the two years has coincided with a project, and I’ve just left the person I was with because I couldn’t divide myself up. If Robert wasn’t as understanding and as confident about who he is… I feel a strain right now in our relationship, but it’s not something that can’t be overcome, it’s just difficult when someone who’s used to having a normal private life ends up in the Worst Dressed People article and gets called a bagel maker. And then I also work from dawn until dusk.

In Moonstruck, there isn’t a man who will look at the wolf scene who won’t feel uncovered, because they’re aware of where the wound is. And the fantasy is that someone beautiful will find you and say, “Okay, I see your damaged hand and I love you for it.” Because it’s the beginning of empathy.

And empathy is not a quality of warriors. It’s what separates men from women. Women have learned it from the cradle on. And it’s the center of the film: you believe in a damaged man. You break your engagement. And abandon the good girl future.

And yet your character attempts something with this guy that is the problem of the Eighties: permanence. Men and women don’t stay together any more, even for the wrong reasons, and yet the movie tells you it’s possible to get married.

One of the things I loved about the movie, and it’s real corny, is there’s a family structure that no matter how it seemed to be weakening or falling apart, it came together in the end—like in a fairy tale. And that people really loved each other and looked like they could be together for the rest of their lives. All the things that are constantly torn down on TV, and in film, and on radio, and in the newspapers.

It was a wish?

Not a wish exactly, but I don’t think if you see Robocop or Running Man or—I could go on for five hours—that you get the same feeling that things are more possible. I thought it’d be really great to be a part of that… even though I don’t live it, exactly. It’s not my lifestyle, I don’t belong to a big family, and I don’t even know if it’s realistic any more. But maybe that was part of it, too.

I remember a time before there was a word “hijacking,” you know, or “serial killers.” You know there were things in my youth—

Serial monogamy?

All right, but it reminds me of a movie that would have been made in the Forties. It’s a little bit naive and a little bit simplistic. And I think that no matter how hip we are, or how cool, or how much in the fast lane, you still hope that maybe that’s still a possibility for you in your life, to find someone that you could be with, and want to be with for the rest of your life.

It just doesn’t seem to happen. Also, the lifestyle that I live is not really conducive to it. I can play it, but I don’t know that I could live it. I’m not a cookie-baking mother. Well, that’s not true. I am a cookie-baking mother. I’m exactly a cookie-baking mother, but I’m not a traditional cookie-baking mother.

I don’t stay home and, my life is filled with so many ups and downs, and addictions to excitement, highs and lows, you know? It’s not like Meryl where she just goes home to Connecticut, and that’s it. We all come to it in a different way. I like doing Saturday Night Live, I like being on stage, I still enjoy singing, rock ‘n roll—as much as I turn my back on it…

It got you to here.

Yeah. I wanted to be an actress and everybody said no, you can’t, you can’t, you can’t. And I just kept saying, Oh, I can, I can, I can. And there were certain things I had to give up to get the chance to do it. That’s why the idea of me having so much control, you know, is silly. But I should be allowed to control some of the things that I do.

Sonny Bono and Cher, 1965. Photo by Kobal/Shutterstock

If you were a 41 year-old man and you were dating a 23 year-old woman nobody would say shit—they might think some stuff. Okay, you got your spurs, you can kick your own horse . Are you afraid of having less say?

I’ve said this before but older men don’t ask me out. I don’t particularly care for older men as a group. I find younger men a lot more fun, a lot more supportive, and a lot more into doing things that I want to do.

First of all, they’re raised by women like me, so they have a different take on women and power, women doing their own job, women who don’t need them to take care of them. I want somebody who still wants to go dancing, or to go to the movies, or play cards, or spend the day at Disneyland , or who’ll give me more than the three hours that he has left after his day at the office.

You’re the one who spends all the time working. You need a wife.

I really work a hard day. When I come home, if I say “Robert will you get me a Coke? Or, if you’re going upstairs will you make pasta?”, it’s not like I’ve said something unreasonable. I want something that’s more equal.

But you’re King Shit here.

Yeah, but not when it comes to him. I’m not Cher in this house, you know? He wouldn’t even call me that. Most of my really close friends don’t call me Cher.

What do they call you?

Bobby calls me Cherilyn: my sister calls me Crud; my best friend, Paulette, calls me Cherilina; my Mom calls me Poke. No one who is truly close to me calls me Cher. And I call Michelle [Pfeiffer] Meesh. I call Meryl, Mary Louise.

Why?

Because that’s her name. Jack gives everyone a nickname except me. “Anyone with the name Cher,” he says, “doesn’t get a nickname.” There’s something about famous people, though, you just need something different.

To feel you’re you?

Yeah. Cher is basically the tip of the iceberg. I’m here to be entertaining, basically. And that’s what it’s about. I think that it’s fun to wonder.