By Amos Vogel in the Fall 1971 Issue

Interview: Bernardo Bertolucci

In this 1971 conversation with Amos Vogel, the Italian master discusses The Conformist and more

Only rarely has a new talent burst upon the film scene with such brilliance as did Bernardo Bertolucci with his Before the Revolution (1963).

Though preceded by his more conventional yet extremely promising The Grim Reaper (1961), based on a story by Pasolini, it was the passionate, violent, lyrical and political Before the Revolution which brought the 22-year-old to the immediate attention of the international film world and won him the Max Ophuls Prize and the Prix de la Jeune Critique in France. Born 1941 in Parma into an Italian bourgeois family, the son of a well-known Italian poet and film critic, Bertolucci (himself a poet and in 1962 the winner of Italy’s most coveted poetry prize) quickly transferred his powerful lyrical, romantic talents from verbal to pictorial images, correctly sensing where his major talents were.

In 1971, with the release of his The Spider’s Stratagem and The Conformist, it is abundantly clear that Bertolucci’s entire work is permeated by a profound, continuing and as yet unresolved tension between a luxuriant, vibrant aestheticism and a possibly artificial endeavor to simultaneously create a radical, politically committed cinema; this is paralleled in his own life by the tension between bourgeois background and deeply felt ideological preoccupations. A profound feeling for a tactile, sensuous, pictorial cinema of (radical) form, decor, texture, color, and composition is balanced in Bertolucci with a strong sensitivity to social issues, a painful understanding of the contradictions of the radical bourgeois confronted with the loneliness and horror of bourgeois privilege in a period of capitalist decline. Unable to give up his class roots, his sensitivity sharpens his political radicalism while blunting it with informed skepticism and profound ambiguity. The motto that prefaces his most important work to date, Before the Revolution, at the same time must serve as the most revealing autobiographical statement of his unending dilemma, painfully expressed also in his subsequent films: “Only those who lived before the revolution knew how sweet life could be.” (Talleyrand).

This is why Bertolucci is at his best in describing, with anguished ambivalence, bitter-sweet episodes of bourgeois life—an evening at the opera, a dancing school, a Bal Musette in Paris, the raptures of young (bourgeois) love, the despair of an Italian aristocrat whose world is being destroyed by capitalist materialism if not impending revolution. (”My films are a way to exorcise my own fears.”) The red flag and the poisonous beauty of privileged bourgeois existence are the two constants of Bertolucci’s life and work: they are expressed in the schizophrenic hero of Partner (1968), in which Pierre Clementi portrays both the bourgeois and his revolutionary alter ego, in fact, one person in the film; in his insistence in The Spider’s Stratagem (1969) that an antifascist hero may have been a fascist spy; and, in The Conformist (1970), on portraying an obnoxious, murderous fascist in the most loving, nostalgic, even romantic settings and situations.

Bertolucci, the rebel of the Italian film scene, instrumental in radicalizing the Italian cinema, comes, with The Conformist, perilously close to making a perfect commercial film that will be appreciated by liberal art-theatre audiences everywhere for its staunchly anti-fascist stance and its loving preoccupation with the sensuous data of bourgeois life, the romantic colors and interiors of a social class in decline, seen by one of its renegade sons. But what is most original in Bertolucci’s work is his totally outrageous and exuberant pictorial sense, his aesthetically revolutionary attempt to create a poetic cinema by means of the most audacious and violent editing and camera devices, far in advance of anything the commercial cinema has to offer except for Godard and Resnais, and surpassing many of the most potent achievements of the international underground cinema.

The pained contradiction that is Bertolucci’s life and strength are brilliantly revealed in the following interview, recorded during Bertolucci’s visit to the 1970 New York Film Festival, at which he was the only director to be represented by two works (The Spider’s Stratagem and The Conformist). The striking success of these two films at the Festival, their acceptance by a sophisticated-and bourgeois-Festival audience, coupled with their basic and beautiful ambiguity, clearly points to the danger faced by this director in his future work. From being the outcast independent of Before the Revolution, appreciated only by the happy few, he has advanced to The Conformist, significantly a Paramount release; the radicalism of the former work, its profound and instinctual originality, has been transformed into the muted, more conventional and achieved brilliance of the latter: only the future will reveal whether Bertolucci is to be the staunch revolutionist he aspires to be or the darling of the liberal bourgeoisie.

The Conformist (Bernardo Bertolucci, 1970)

It seems to me that there exist two kinds of cinema: a visual and a literary one. And sometimes I think that the literary cinema is not cinema at all, since it only utilizes visuals as illustration for a story or plot; it traffics in words, while the visual cinema deals with images. I see hundreds of films every year and with most of them,I could keep my eyes closed and would still understand the story. This is a very strange problem since these are precisely the films considered most important in today’s mass market. Since you are one of the most important new directors of the “visual” cinema, I wonder what you think of this problem.

I don’t attribute the same meaning as you do to the term “ literary.” For me, “literary” is very close to “visual.” For what you call “literary,” I’d like to use a different term “theatrical.” Or “filmed theater.” The cinema is much closer to literature and poetry than to the theater. I agree with you that often cinema is merely an illustration of a story. That is the biggest danger you face when you make a film from a novel. That was my problem when I made The Conformist, which is based on a Moravia story. But anyway, it’s an every-day problem in the cinema, because many filmmakers use their scripts as if they had started from a novel; they simply make an illustrated film of the script. On the other hand, I, too, start from a very precise script-but only in order to destroy it. For me, inspiration exists only at the moment of actual shooting. Not before. For me, the cinema is an art of gestures [un art gesture]. When I find myself on a set, with actors and lights, the “solution” I find for a certain sequence, a certain situation, does not come from a preconceived idea, but from the musical rapport that exists between the actors, the lights, the camera, the space around them—and I move the camera as if I was gesturing with it. I feel that the cinema is always a cinema of gestures—very direct, even if there are fifty people in the crew.

But imperialism is an enemy of these “gestures,” of the assembling of the daily rushes into an ensemble of gestures. The moment of imperialism is the editing of the film. This is when one cuts out all that was direct and “gesticular” in the rushes; this is the moment when the producer takes over. He takes the electrocardiogram of the film and cuts out all the high points, in order to create a flat line. I know that in America, the producer wants the right of the final cut, to change or edit the film after the director is through with it, even if he leaves the director completely free during the shooting. When I made Partner, I had an obsessive idea in my head and tried to solve it by avoiding to edit the film except to put it into the right order. After Partner, I realized that I had been too neurotic about this problem. And so I found another solution for The Conformist and The Spider’s Stratagem: I employed editing to underline the “gesticulation” [gestualite] of the film.

You said you wanted a precise script, but only to destroy it; but what is in the script—is it description of scenes and dialogue or detailed shot instructions, camera set-ups, and movements?

It is only a script of situations and dialogue; it contains nothing about camera or its placement or about the actual shots. The script is a starting point for me—you have to have one-but that’s all …

Yet, when one looks at your films, they are very complex and advanced, not merely stylistically, but in terms of editing as well. This is why I am not quite clear why you counterpose editing to shooting. For example, there is a scene in Before the Revolution, which involves a young man, Agostino, on a bike. Agostino is distraught and this is conveyed by means of jagged camera movements, interrupted action, cutting from long-shot to closeup and zoom without any transition. It is a beautiful sequence, very short, mysterious and unpredictable, created by the way camera and actors move within the frame, and by editing, tempo, length, and order of the shots. The scene could have been killed in the editing.

Well, I was there and I happen to know how it all happened; in fact, it’s an example of why I feel the film is conventional. I believe that a film should be “all there” at the moment of shooting. When I see a sequence like the one you mentioned, it smells of manipulation. I had shot this sequence with two cameras-one with a wide-angle lens, the other with a zoom lens. This already indicates to me that I was somewhat undecided about the sequence. I shot it as I would a boxing match, thinking that I would fix it up in the editing and this is not good for me. All you can get from editing is a little bit of manipulation.

Well, “manipulation” is inherent in any sequence, in the way it was photographed, “set up” and edited to give it a particular tempo and character. Doesn’t art constantly—and inevitably—manipulate reality?

Not in the shooting. The shooting is just “a happening” [in English], it’s a rapport between me, the camera and what is present…

The Conformist (Bernardo Bertolucci, 1970)

Do you think all editing is manipulative?

The editing of Griffith, Eisenstein, Vertov was not manipulative, but a great invention.

But Eisenstein, especially, has been accused of intellectual manipulation and even formalism.

No, in my opinion editing becomes manipulative only when it is taken over by the producer. Before that, it’s a sublime invention. But even if my producer does not oppress me, the editing itself has today become manipulative.

But what about independent or underground filmmakers who don ‘t even have a producer?

In their films there is even more manipulation than in normal films because, in the underground cinema, there is the same refusal to accept the so-called commercial, establishment cinema that certain young bourgeois express against their fathers; but, as their fathers are, in a sense, far removed from them, the sons are somehow integrated into society anyway. The underground cinema is merely the other side of the coin of the Hollywood cinema; it’s a reaction that remains within the framework of Hollywood. In a more banal, simple sense, there is a great love for Hollywood in underground films; when they want to be perverse, or against the official morality, they are as innocent as young school girls. They do all the things their masters told them not to do; now, that is nice, but it’s not revolutionary. But remember that I speak of editing here not as a theoretician; I only express a certain unhappiness. In ten days, I might change my mind.

There is a scene in The Spider’s Stratagem in which Athos, the young protagonist, leaves a building. He walks to the right, out of the frame; behind him is a startling, very blue wall; he has already left the frame, but you decided to have us look at this blue wall for another several seconds. Now this is an editing decision.

No, it’s a shooting decision.

But during the editing, you decided to keep this footage in the final film and not to cut when he leaves the frame?

I had already decided this before the shooting ; otherwise I would have told my cameraman to cut.

And so the “divine moment” is in the shooting, not in the editing?

Not “divine”…

The supreme human moment is in the shooting?

Yes, definitely.

This is very different from the views of many other directors, including the early Russian revolutionary directors. According to them, a film is born only in the cutting room.

There is something fundamental I want to say about all this: When there are no ideas in the shots, you cannot insert them by means of editing. The idea has to be there during the shooting. Welles’ The Magnificent Ambersons, for example, has long, long takes and no editing and is one of the more extraordinary examples of non-editing; or rather, filmic creation at the moment of shooting…

But when you call editing an imperialist device, it’s really not the editing but rather the intervention of the producer you refer to?

Yes, in fact, I said earlier that editing was a beautiful invention, an expressive device; just like the trade unions were great at one time; but in the next moment, capital stepped in and interfered in the unions, like in America.

The Conformist (Bernardo Bertolucci, 1970)

I am struck by the stylistic differences, between The Spider’s Stratagem and The Conformist and your earlier Before the Revolution. Do you consider these new films to be an advance aesthetically or do you merely wish to indicate that the staccato, avant-grade style of Before the Revolution was only appropriate for that particular, passionate, almost autobiographical subject? After all, the style of your last two films is much closer to conventional narrative cinema, with lyrical and poetic components.

I believe that these films are like three different ways of loving three different women. There are different ways of loving. I made Spider’s Stratagem immediately before The Conformist, but even though there were only a few short months between them, my psychological situation was different. And that is why these two films are so different. I made The Spider’s Stratagem in a state of melancholic happiness and great serenity and The Conformist in a tragic state of great psychological upheaval. As to Before the Revolution, I do not remember.

It’s in the film. As to The Conformist, it will easily be acceptable to the American art-theatre public, both politically—as an antifascist film—and aesthetically. This is not true of Before the Revolution, a very private, very special work, in fact, a cult film for a small group of cineasts and critics.

I like that very much…

That it has become a cult film?

No, that with The Conformist, can now speak to a wider audience: it is possible that I make films because, in real life, I cannot communicate; and this way I communicate with lots of people. In this sense, Victor Fleming was a very fortunate person… He made Gone With The Wind… [Laughs] Fleming communicates with everybody.

But this reminds me of the strange remark you made during your New York Film Festival press conference following The Conformist, when you affectionately referred to it as “your commercial film,” “a bit of whoring” on your part, and then smiled in a devilish way.

Yes, I said it and I meant it and I hope it is true. What gave me a sort of devilish appearance is that I know that The Conformist is my most difficult film and that amuses me very much. It seems to be my easiest film, but actually it is the most difficult because it is the simplest one. One enters it on a first level of “reading” that was missing from Before the Revolution: that film had many other levels but there did not exist a first level of reading as soon as you saw it. In The Conformist, there is such a first level, so everybody enters it and poses no further problems to himself. Instead, the film is full of other levels. This is the trick of the great Hollywood directors: in Europe, we needed thirty years before some young French critics made us realize that the American cinema was something more than what had been thought of until that moment.

At your The Conformist press conference, you also said: “The destruction of structures in Partner is, in The Conformist, followed by a very definite structure.” But isn’t the “destruction of structures” one of the signposts of contemporary cinema, the cinema of Godard and the underground; and also of modern literature, painting, music, poetry?

Yes, definitely. In the cinema, Godard started it. In music, Schönberg. But The Conformist arrives at a moment when I myself, looking around in cinema, realize that this destruction of structures has itself become the new establishment, not only in my film but in those of others. I think we need more plot and structure now. Perhaps it is fear, I don’t know.

Well, there was plot in Partner and Before the Revolution too, a looser, more dissociated, modern kind of plot.

I mean, we need more solid structures. Maybe this is a fear of aestheticism and a feeling that the avant-garde is itself bourgeois…

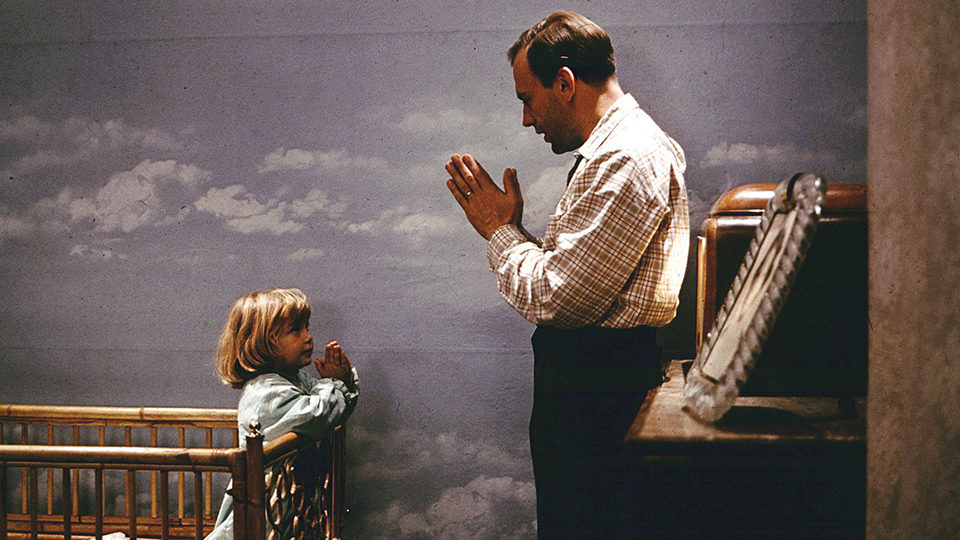

Before The Revolution (Bernardo Bertolucci, 1964)

But radical, revolutionary cinema can be either “agitprop” or artistic, and I think that your lyrical “aestheticist” Before the Revolution is more effective politically than Godard’s latest agitprop works.

I don’t know. All these films are political and none have political effect because they are only shown at festivals so that they do not reach an audience wide enough to be affected politically.

Yes, but your new fear of aestheticism is a danger because your strength is precisely in your “aesthetics.”

I know, but I also fear this aestheticism, because I know very well that I can make a film about the quality of wind—the essence of wind which is nothing—and it will make festival audiences happy. I am afraid of doing that. Aestheticism is always a mistake. Perhaps in Italy, this word has different connotations; in Italy, it’s a pejorative term. I hope there is just as much need for political consciousness in me as there is for aestheticism. Perhaps I shall make my best films dealing with politics without talking about politics.

But don’t you believe that the art of a future, classless society will be a flowering of the most varied tendencies, styles and schools; not agitprop tracts about how to make more tractors or how to fight imperialism, but an “aesthetic” art that celebrates life? We should not lose that now, even if one fights for a better society.

But unfortunately, I think I am definitely the last one to lose this aestheticism.

You haven’t lost it yet, have you?

No…

But you’d like to.

Yes, that’s my problem. I am much more complicated than I seem to be. To have been born into the “cultured bourgeoisie” is much more complicated than what the young agitprop kids think. I am against their famous phrase—“Degree Zero”—which signifies that we have to start from scratch in building a new society and culture. I find it absolutely idiotic and anti-Leninist. It’s even a bit fascist, but much used by the young people. It is a neurotic, masochistic, self-lacerating phrase because to say we have to start from zero is like saying we have to start from the caves, and I don’t want to start from the caves.

Speaking of “empty aestheticism,” the most evocative scenes in your film are precisely the most mysterious, “irrelevant” and poetic ones. Are you going to stop doing this kind of film because you are afraid of aestheticism?

There is a conflict within me… a very acute conflict. And if it weren’t for that I might be dead.

FILMOGRAPHY

(1941– )

1962

La commare secca (The Grim Reaper)

Producer: Antonio Cervi

Screenplay: Pier Paolo Pasolini, Sergio Citti and Bernardo Bertolucci; from a story by Pier Paolo Pasolini

Photography: Gianni Narzisi;

Music: Carlo Rustichelli

With Francesco Ruiu , Giancarlo de Rosa, Vincenzo Ciccora, Allen Midgette

100 minutes.

1964

Prima della rivoluzione (Before the Revolution)

Production company: IRIDE Cinematografica

Original screenplay: Bernardo Bertolucci

Photography: Aldo Scavarda

Music: Gino Paoli

With Adriana Asti, Francesco Barilli, Allen Midgette, Morando Morandini

115 minutes.

1968

Partner

Producer: Giovanni Bertolucci

Screenplay: Bernardo Bertolucci and Gianni Amico; from The Double, a novel by Fyodor Dostoievsky

Photography: Ugo Piccone (CinemaScope and EastmanColor)

Art Direction: Jean-Robert Marquis

Editor: Roberto Perpignani

With Pierre Clementi, Stefania Sandrelli, Tina Aumont, Sergio Tofano

120 minutes

1969

Strategia del ragno (The Spider’s Stratagem)

Producer: Giovanni Bertolucci

Screenplay: Bernardo Bertolucci, Edoardo de Gregorio and Marilu Parolini; from the short story by Jorge Luis Borges

Photography: Vittorio Storaro (Technicolor)

Art director: Maria Paola Maino

Editor: Roberto Perpignani

Music: Arnold Schoenberg, Giuseppe Verdi

With Giulio Brogi, Alida Valli, Tino Scotti , Allen Midgette

100 minutes.

1970

Il conformista (The Conformist)

Producer: Maurizio Lodi-Fe

Screenplay: Bernardo Bertolucci; from the novel by Alberto Moravia

Photography: Vittorio Storaro (Technicolor)

Art director: Ferdinando Scarfioti

Editor: Franco Arcalli

Music: Georges Delerue

With Jean-Louis Trintignant, Stefania Sandrelli, Dominique Sanda, Pierre Clementi, Gastone

Moschin

112 minutes

Amos Vogel, the godfather of independent cinema in America, writes frequently for The Village Voice.