By Sheila O'Malley in the January-February 2019 Issue

In Memoriam: Nicolas Roeg

The cinematographer turned director blew our minds to show better what makes us tick

A drawer filled with cuff links. A wall splattered with red liquid. A dizzying helicopter shot of a car racing through city streets. Naked writhing bodies. A clock ticking. Naked writhing bodies again. Nicolas Roeg put shots together like this, abolishing connective tissue and banishing linear time. His work is as unique to him as a fingerprint or DNA, and so imitated that it’s now part of the conventional language of filmmaking. What is not easy to imitate is the emotional impact of his style, how personal his vision was. Roeg’s work plunges you into the pool of the unconscious, where symbols equal reality, where everything is about sex, where the thought nags, “Something meaningful is going on here, if I could just figure out what it is.” “My interest is energy. Transference of energy,” says Newton (David Bowie) in Roeg’s The Man Who Fell to Earth, and the same could be said of its director.

From the January-February 2019 Issue

Also in this issue

Roeg started as a cinematographer, best known for his work on Richard Lester’s Petulia (1968). His sensitivity to the weirdness of the modern world would factor in his films as director, the list of titles almost daunting: Performance (1970), Walkabout (1971), Don’t Look Now (1973), The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976). His work continued through the ’80s, with challenging films like Bad Timing (1980), Eureka (1983), Insignificance (1985), Castaway (1986), Track 29 (1988), and The Witches (1990). Yet his most fruitful era was the 1970s, when traditional filmmaking began to break apart, a process already started in the 1960s (and pioneered by the Surrealists long before).

“I realized I’ve spent all my life creating a past,” the filmmaker once said. The comment is key to understanding his work; so much of it has to do with the Proustian fluidity of time. Performance, Roeg’s directorial debut (co-credited with Donald Cammell), is an erotic fever dream, so controversial it wasn’t released for two years after completion. Four sexually fluid characters—played by James Fox, Mick Jagger (Roeg loved casting famous musicians), Anita Pallenberg, and Michèle Breton—swan around in a cluttered London house, bickering, having sex, bathing, hiding. The dialogue is oblique and circular: “I feel like a man. A man all the time.” “That’s awful. That’s what’s wrong with you, isn’t it?” Performance is disorienting and dazzling, with Jagger a destabilizing sexual persona stalking through it like a panther. To call it a “debut” doesn’t sound right. It’s more like a declaration of independence.

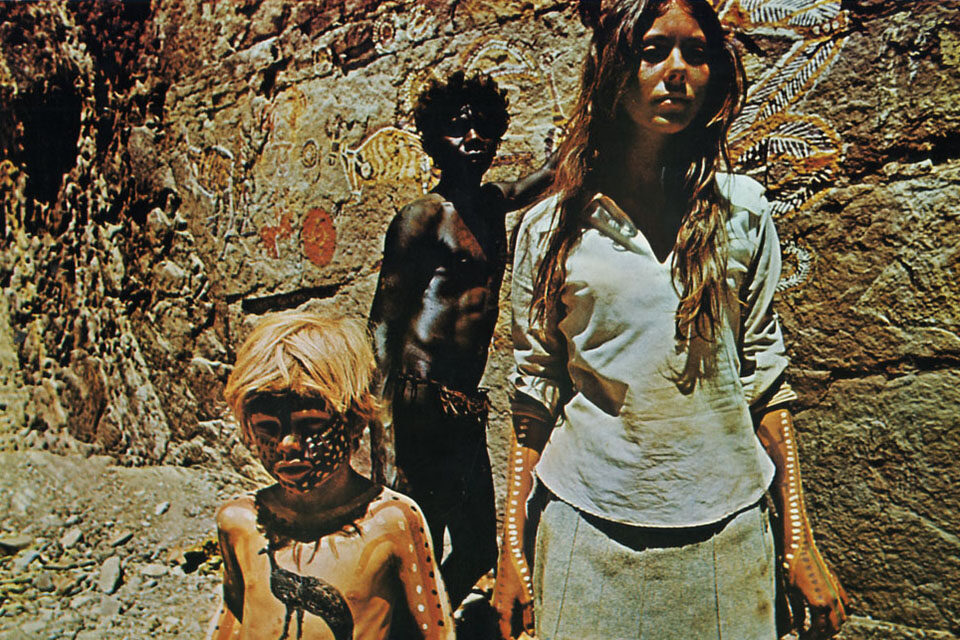

Walkabout

His next film, Walkabout, had a more traditional arc—two children (Jenny Agutter and Luc Roeg, his son), abandoned in the Austalian outback, are rescued by a young Aborigine man (David Gulpilil)—but was filmed with the same audacity, leaping between the micro and the macro. The three characters exist in an innocent Eden, although the doomsaying voice on the transistor radio drones about human society coming to an end. Audiences and critics were baffled by Performance; Walkabout got their attention. Then came an unnerving masterwork: Don’t Look Now seethes with ominous portent from the first astonishing scene (a collage of images juxtaposed so alarmingly that the source of dread can’t be located), the unconscious screaming warnings from beneath our surface reality. Exquisitely designed, each scene is pierced with the color red—curtains, scarves, ink, boots, long johns on the line—connecting with the daughter’s red slicker, and the hooded figure scurrying through the Venice night.

Objects and motifs repeat in Roeg’s films. Clocks. Mirrors. Cars. Radio and television shows commenting on the action (in Track 29, Theresa Russell skulks through her house, while a similar scene from Cape Fear plays on the TV). Extreme close-ups butt against enormous vistas. Raw sex scenes unfold, but they are constantly interrupted, the most famous example being the scene in Don’t Look Now, intercutting the sex of Donald Sutherland and Julie Christie’s married couple with shots of the two of them dressing to go out later.

Yet Roeg’s next film, The Man Who Fell to Earth, is his most explicit exploration of time: months pass, years, decades, characters grow old, but Newton—the alien come to earth played by David Bowie—is unchanged. A man outside time, Newton’s loneliness is existential and devastating. Bowie is so extraordinary-looking, with his translucent different-colored eyes and his lean ivory-skinned body, that Roeg revels, visually, in his disorienting presence: the reality of it, its strangeness and beauty.

The Man Who Fell to Earth

Roeg started off the 1980s powerfully with Bad Timing, his first collaboration with Theresa Russell (whom he would eventually marry). Her ferocious and assured performance (she was only 23) nearly blows her much more experienced co-stars Art Garfunkel and Harvey Keitel off the screen. A portrait of sexual obsession, Bad Timing includes one of the most disturbing scenes in all of Roeg’s work: uptight Alex (Garfunkel), who has been emotionally tormenting and stalking his free-spirited girlfriend (Russell), finds her in her apartment overdosing on drugs, nearly unconscious, and instead of calling an ambulance, he rips off her camisole with a knife and has his way with her unresponsive body, grunting down at her, “Anything to get you back.”Bad Timing is one of the most unblinking—and terrifying—portraits of male jealousy in film.

Obsession is the theme again in Eureka, where Gene Hackman (in a great performance) plays a gold prospector saved by seemingly supernatural forces. Roeg’s use of flashbacks and flash-forwards, his fascination with identities merging or mirroring, is in high gear throughout. Insignificance, adapted from Terry Johnson’s play, is one of Roeg’s more conventional films, even though it portrays an imagined meeting of Albert Einstein (Michael Emil), Marilyn Monroe (Russell again), Joe DiMaggio (Gary Busey), and Joe McCarthy (Tony Curtis). In one of the most memorable scenes, Marilyn—wearing the famous white Seven Year Itch dress—burns up in an atomic blast, destruction unfurling around her for a full three and a half minutes.

In Track 29, Gary Oldman’s Martin may or may not be the child Russell’s Linda was forced to give up for adoption years before. Oldman and Russell invest this material with emotional hysteria and sexual sickness, so neurotic and trapped that you yearn to escape from the both of them. Track 29 is not an ingratiating film, nor does it want you to “warm” to anyone on screen. If Track 29 had been released in 1978, as opposed to 1988, it might have found an audience. Roeg’s 1989 made-for-TV adaptation of Tennessee Williams’s Sweet Bird of Youth, starring Elizabeth Taylor and Mark Harmon, shows Roeg could do traditional when called upon (and he films Taylor beautifully, in true “star close-up” style). But Sweet Bird of Youth is filled with Roegian touches: a relentless ticking clock, a strained kiss through a chain-link fence, a vanity mirror quadrupling Harmon and Taylor’s reflections. Then came The Witches in 1990. Deliriously upsetting and violent, with Anjelica Huston’s frightening performance at its center, the film features children being turned into mice or tortured while howling witches laugh at them. The angles are stark and dramatic, with plenty of Roeg’s signature gigantic zooms from a far distance. This is what a Nicolas Roeg movie “made for kids” looks like.

Bad Timing

Many of the directors’s films received baffled or outright irritated reviews. Audiences sometimes recoiled from the challenges of his visuals. Roeg calls us out on our dirty minds, our voyeurism, making us admit things we might not want to acknowledge. The films were often marketed incorrectly, and Roeg had a lot to say about the damage that caused: “Any change in form produces a fear of change, and that has accelerated.” There was nothing “familiar” about Roeg’s work, and it is only with time that we can perceive the enormity of its influence.

In a 2011 interview with Criterion, Theresa Russell discussed Roeg’s editing style, revealing the logic behind his choices, his Jungian leaps, his Joycean attention to the workings of the human mind—its mysteries and ambiguities: “People were confused by the way [Bad Timing] was cut. But to me, it was perfectly obvious . . . People don’t think linearly. You think kind of back and forth and up and down, you don’t think A-B-C, in chronological order. People had a problem with that. But now when people see it they don’t even mention that, because people are so used to that . . . I really think that Nic changed the grammar of film. It was ahead of its time.”

As William Butler Yeats wrote of Jonathan Swift: “Imitate him if you dare.” Nicolas Roeg has many imitators, but few heirs.

Sheila O’Malley is a regular film critic for Rogerebert.com and other outlets including The Criterion Collection. Her blog is The Sheila Variations.