By Amy Taubin in the July-August 2017 Issue

Free Range

With Okja, Bong Joon Ho creates his most dramatically protean adventure yet—a work of interspecies friendship, galloping satire, and monstrous truths

The Wages of Fear” was Bong Joon Ho’s answer to my question, “What was the first film that made a big impression on you?” The Korean director saw Henri-Georges Clouzot’s 1953 thriller on TV in the mid-1970s when he was about 8 years old. He remembers being so overwhelmed that he wouldn’t get up even to go to the bathroom. “It was very traumatic,” he says of the scene where Mario (Yves Montand) drives a truck filled with explosives over his buddy’s leg, rather than risk getting stuck in an oil spill and losing the paycheck that awaits them at delivery. “It left a film scar,” said Bong, adding that in everyday life he is a fearful person and that fear is an exciting emotion.

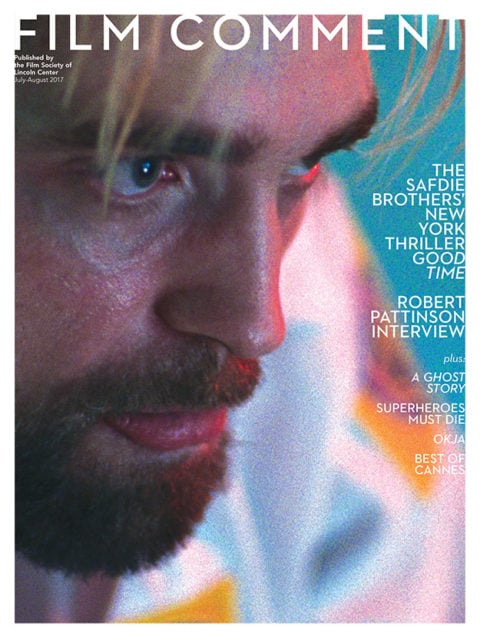

From the July-August 2017 Issue

Also in this issue

High on my list of petrifying movie scenes is the moment toward the end of The Host, Bong’s 2006 monster movie and his first global box-office hit, when the pre-adolescent girl (Ko Ah-Sung) who has been abducted by a mutant amphibian—it grew to dinosaur size in the Han River by ingesting chemicals illegally dumped by American military scientists—makes one last desperate attempt to escape from the monster’s sewer lair. Covered in filth and blood, having just avoided being crushed by the creature’s anaconda-like tail, she is stopped dead by a yellow-bodied spider crawling up her skirt. The monster is very big, the spider very small, and yet the latter is even more terrifying. Like the image from The Wages of Fear that “left a film scar” on Bong, the spider is registered by the character’s senses of touch and sight. Similarly, in the most indelible moment in Bong’s latest film, Okja, pre-teen heroine Mija (An Seo-Hyun) looks down when she feels something icky on her legs only to discover that she is ankle-deep in blood. The image marks the moment in which Okja completes its gradual metamorphosis from a satirical action-adventure into a full-fledged horror movie. And again, the moment hinges on our empathetic connection to a character’s senses of sight and touch, mutually confirming the gruesomeness of her experience.

The most controversial film at Cannes 2017, Okja was financed by Netflix, which had long planned for a day-and-date release worldwide a month after the festival ended. By law in France, a three-year window is required between a feature film’s theatrical exhibition and its release in the home market. Netflix’s business model thus doomed Okja, at least in France, to being merely a TV movie. Condemned f or programming it in the hallowed Competition, the festival promised to abstain from Netflix, thus guaranteeing that the Cannes main slate will be even more irrelevant to film culture in the future than it already is. On several occasions in Cannes and after, Bong said he had directed Okja as a big-screen picture, but, practically speaking, he thought it was fine to look at it in a home theater, hopefully with good sound. He does not approve, however, of streaming it on your phone, and he specifically shot a few scenes that would not be legible on a screen that small.

Exhibition strategy aside, Okja polarized the press. After the first screening at Cannes, as I was trying to conceal my tears, a critic with whom I seldom agree, but respect for his measured judgment, asked me if I had seen “that abortion.” I was puzzled by the uncharacteristic vitriol in his immediate reaction. And while many critics wrote enthusiastically about Okja, the negative reviews were scathing, most faulting the movie for switching genres midway, as if that were an aesthetic crime or perhaps a scam to lure audiences. After a brief satiric prologue, Okja becomes a charming, even rollicking comedy about a girl and her very large companion animal, only to darken as Mija and the audience become aware of the horror that awaits Okja, like all animals that are treated by the global factory farming industry as property from which profits must be maximized. Bong has always mixed tonalities in his movies, from the broad slapstick that punctuates the bleak melodramas Memories of Murder (2003) and Mother (2009) to the casting of the Korean star Song Kang-ho, best known as a comic actor, in leading roles in Memories and The Host. Song’s performance in Bong’s dystopic Snowpiercer (2013) suggests that he is one of the few actors who could play, with equal brilliance, the title role in King Lear and also the king’s Fool.

The way in which humans ease their most painful experiences by joking around is a commonplace in life and movies. But Okja does something slightly different. For Bong, the movie reflects what we might do in the course of a day. We bond with the dogs and cats that live with us and then we sit down to a steak dinner, without a thought about how that steak got onto our plate. The third act of Okja depicts the animal holocaust that we deny in order to indulge our customary pleasures. I’m quite sure that some of the negative reaction to Okja at Cannes was from critics who were looking forward to a jambon-beurre sandwich for lunch and didn’t want to think about the suffering of pigs as they ate. Bong is not a vegetarian, although his co-writer Jon Ronson is. By now, Bong must be tired of explaining that he eats fish and some chicken but almost never red meat. He points out that at the end of the movie, Mija and her grandfather eat chicken stew while Okja and the piglet that Okja smuggled from the slaughterhouse in her mouth watch from the yard. (They are the only holocaust survivors.) The chicken is “free-range,” raised by Mija. Okja is a condemnation, not of all meat-eaters, but of factory farming, one of the largest engines of capitalism and, according to some studies, a producer of huge quantities of methane, a pollutant that does as much damage to air and water as fossil fuels.

Okja originated in Bong’s desire to make a movie about the bond between a young girl and the animal she grows up with. That Okja is a fantasy creature—in fact a computer graphic image—deepens the representation of love between her and Mija because it must overcome the profound difference between the live action of the girl and the animation of the animal. “I am I because my little dog knows me,” wrote Gertrude Stein, but exactly how do humans and animals know each other? Bong gives us time to meditate on that question in the first act of the film, in which Mija and Okja play in the forest, foraging and fishing for food, and Okja demonstrates her intelligence and loyalty when she saves Mija’s life. Bong’s filmmaking is distinguished by his bold use of scale, in particular, the giant, full-screen close-ups of his actors’ faces. He notes that there are certain actors whose faces are so expressive that he wants the camera to get as near to them as possible. When I interviewed him in New York, he mentioned Kim Hye-ja in Mother, the first female actor to play the lead role in one of his films. His second female lead is An in Okja, and she too has several stunning close-ups (the cinematography is by Darius Khondji). But just as remarkable here are two two-shots of Mija and Okja, in which Mija’s face in profile rests on Okja’s cheek but it’s Okja’s eye that dominates the shot. The image confirms the obvious—that the eye of the six-ton Okja is as large as Mija’s face—but it also does something magical: it makes believe that Okja is real and that she and Mija are inseparable. We believe in Okja’s reality not only because An as Mija relates to her as if she is there, but also because of the extraordinary digital animation of that eye. (Erik-Jan De Boer gets credit as VFX supervisor and Okja’s creator.)

The first-act pastoral ends abruptly when Okja is taken away by the Mirando Corporation, which created her in their lab, gave her to Mija’s grandfather to foster, and now reclaims their property to use in a superpig contest—window-dressing for a company attempting to overcome its image as a former manufacturer of napalm—before she’s sent to the slaughterhouse with hundreds of others. Mija grows up fast as she follows Okja from Korea to New York. The tone of the second act—a coming-of-age/ road movie—is initially high comedy, an opportunity for Bong to stage ingenious chases, as when Okja careens through a shopping mall to the strains of John Denver’s “Annie’s Song.” (“You fill up my senses…” Indeed she farts and poops with abandon.) The soundtrack also mixes the Isley Brothers, klezmer-like polkas, and tangos, until, near the end of the third act, a bit of Bach’s “The Well-Tempered Clavier” plays softly as Mija, now a woman of the world, buys Okja’s freedom with the solid gold pig her grandfather intended for her dowry.

As she and Okja leave the slaughterhouse, the hundreds of pigs about to die raise their heads and groan in salute. Only a master filmmaker could knit these sounds and images together without making us feel emotionally manipulated. Indeed, my mind and heart were singularly free, allowing me to puzzle things out on my own from beginning to end.

Closer look: Okja opened in New York and Los Angeles and is available on Netflix.

Amy Taubin is a contributing editor to Film Comment and Artforum.