Galvanized by the intersection of personal, subjective rumination, and social history, the essay has emerged as the leading nonfiction form for both intellectual and artistic innovation. In contrast to competing genres (the PBS historical epic, the updated vérité portrait, the tabloid spectacle), the essay offers a range of politically charged visions uniquely able to blend abstract ideas with concrete realities, the general case with specific notations of human experience. The filmmaker’s onscreen presence-like similar gestures by New Wave directors, an acknowledgment that what goes on in front of the camera bears the imprint of a distinct sensibility behind it—is not in itself an infallible guide for tagging this notoriously tricky form, but it reminds us that a quality shared by all film essays is the inscription of a blatant, self-searching authorial presence. Admittedly, some prominent essayists—Harun Farocki, Harmut Bitomsky, Patrick Keillor—are far from household names. Nonetheless, it’s helpful to remember that the essay has been around for 50 years—Jean Rouch’s Les Maîtres fous (55), Alain Resnais’s Night and Fog (55), and Chris Marker’s Letter from Siberia (58) are crucial milestones—and has been an occasional source of inspiration for the likes of Welles, Godard, Ruiz, and Herzog.

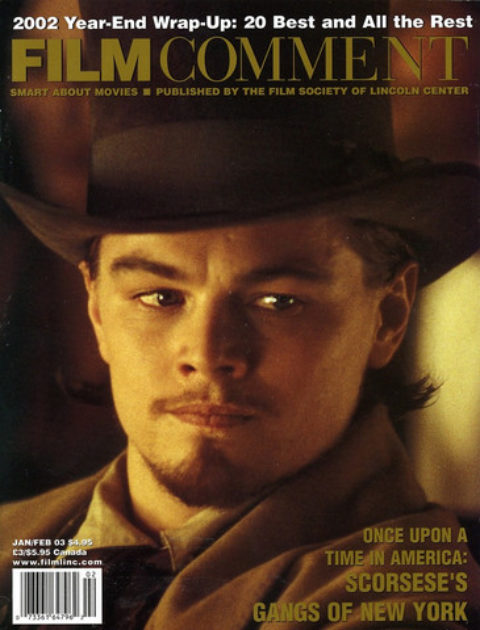

You can read the complete version of this article in the January/February print edition of Film Comment.