Mr. Gardner is Director of the Film Study Center, Coordinator of Light and Communication in the Visual Arts Center, and Lecturer on Visual Studies at Harvard University.

About two weeks ago, there appeared in all the newspapers of America a report prepared by the Surgeon General that clearly and bluntly told the American people that whoever smokes cigarettes is taking a grave risk of contracting lung cancer. I don’t think this report should stop people from smoking cigarettes, but perhaps it will bring about research into the invention of a type of cigarette that does not cause cancer. I would like to see started here in Florence a “Surgeon General’s Report” concerning the ill effect of television, because it is my firm belief that, at least in America, people are dying, mentally and spiritually, of television. Again, I do not think that people should abandon television, but perhaps there will come about some new ideas and new programs to offset the cumulatively evil effects of present day viewing.

It is an established fact that in my country almost one hundred million people spend more time watching television than doing anything else but sleeping. Television in my country, with rare exception, offers little else than idiotic entertainment or superficial journalism. Yet four or five hundred million man-hours a day are squandered by Americans who, either through habit or hope, sit expectantly in front of their sets. They are right in expecting something better, and last November the fantastic potential of television to discover and communicate reality was shown the day President Kennedy was killed and for several days that followed.

I am certain that one of the reasons my country recovered so quickly from that shock is that virtually everyone was able to share, through the careful and complete television documentation, all aspects of the tragedy. All America took part in the death and in the grief over that death. This was the greatest achievement of American television so far. We all became privileged witnesses to history. Why are we not permitted to be witnesses in other far less dramatic but still significant facts of life? Why is television so often divorced from reality? Why can’t we participate in the countless experiences of people throughout our own countries and the world? Only as soon as people can see and share the true experiences of other people can real understanding begin. I suggest that we assign ourselves the task of exploring the possibility of doing just that-of sharing by means of television the limitless real experiences of all people. It would be a true renaissance and quite fitting to begin here in Florence.

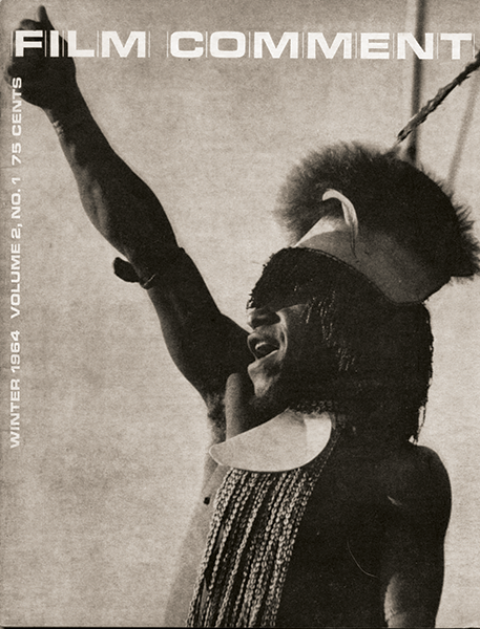

Dead Birds is one of the major results of the Harvard Peabody Museum Expedition to New Guinea. The expedition was under my leadership and included Peter Matthiessen, writer; Karl Heider, ethnographer; Eliot Elisofon, photographer, and Michael Rockefeller, sound technician.

The expedition was designed to study a single location and society in the Dutch New Guinea Highlands. The approach was anthropological, ecological, and pictorial. We wanted to study a warring society unaffected by technological or missionary contacts. As soon as we found the people and place we wanted, the long effort to learn the language and understand the behavior of the selected group began.

It was about two months before serious cinematography began. I knew from the start that my approach would be non-directorial, and I wanted time to familiarize myself with the kinds of behavior I would eventually be photo- graphing. The society we were studying was immensely vigorous and complex. This meant that even if I took a non-directorial role I would have to be extraordinarily selective. I had chosen the theme of aggression in choosing the mountains of New Guinea, and so the film had from the beginning a definite objective. I knew also that the way in which I wanted to structure the film would involve working intimately with two or three specific individuals. They would, in a sense, tell their own story. The culture would become explicable through their actions and reactions. One would, hopefully, see the working out of violence and its attendant consequences, by being able to identify with real individuals.

I shot about 40,000 feet of Ektachrome. I edited this to approximately 3,000 feet in the finished film.

Dead Birds, I like to think, is anthropological in the largest sense—that is to say—human. If it is successful, it should speak about human violence everywhere—not simply in a remote mountain valley of New Guinea.

The film is under option for a Network TV release in the U.S. My policy with respect to this release is to get it to as many viewers as possible. BBC wants it; the Netherlands, the U.S.S.R., Italy will give it a theatrical release, and other countries, such as France and Germany, may easily follow.

All financing of the expedition, which included cost of film, was provided by the Peabody Museum at Harvard and The Netherlands Government.