By Jim Supanick in the May-June 2011 Issue

Reverberation

Claire Denis and the music of Tindersticks (Expanded Version)

R. Murray Schafer coined the term “schizophonia”—the splitting of sound from its source—to define the peculiar nature of audio recordings and to suggest that, in a sense, we’ve learned to live with ghosts. The culture industry that thrives by this process of separation breeds its own apparitions; perhaps the most curious among them is the commercially available film soundtrack. Further splitting sound from its (putative) source, the soundtrack as recording leads us to ask: can the music stand alone as a listening experience? Does it conjure the images to which it was once attached (and is that a desirable effect)? Will it now become the soundtrack in the shared space of its listeners?

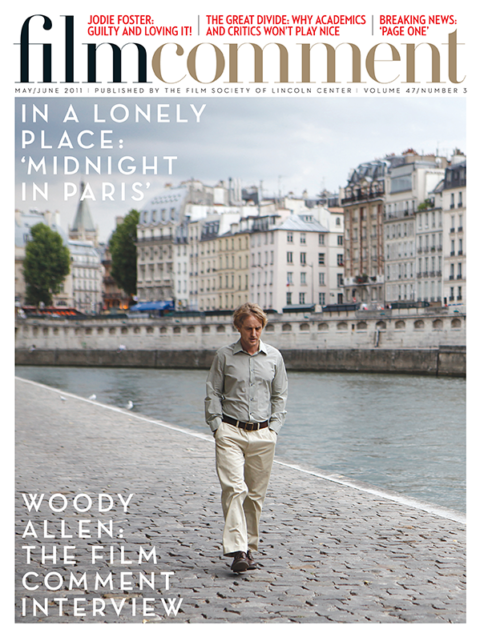

From the May-June 2011 Issue

Also in this issue

These and other questions arise while listening to the deluxe, limited edition five-CD box set of collaborations between Claire Denis and Tindersticks just released on the Constellation label. Supplemented with a booklet of film stills and an essay by Michael Hill, its sheer heft as an object belies the ghostly life of its contents apart from the films. Implicitly too it asks—in an age of single-song downloads—to be heard as a cohesive body of work. And with four of these six soundtracks previously unreleased, we now get a chance to take stock of a whole other side of the group’s output.

Right off I must admit to approaching this set with hesitation, having found the music the band is known for to be a brand of café-bred ennui I quickly tire of: “We all have our croissants to bear” as one self-mocking fan site poster put it. Mostly this was attributable to singer Stuart A. Staples, whose vocals are largely absent here. With their film scores, however, these Prozac refuseniks reveal other depths, with a surprising versatility from one film to the next; sounds range from a melodica weaving through the Fender Rhodes-drenched weather of 35 Shots of Rum, to the burred menace of the guitar figure that spreads itself insistently across nearly all the cues of The Intruder (conceived by Staples apart from the group). Their ensemble interplay has solidified with more recent efforts (with personnel changes surely a factor), no longer the unsteady wobble audible throughout parts of Nénette and Boni, their earliest score for Denis.

35 Shots of Rum

Sound is spacious throughout, with hardly a wasted note. Much of what makes their best music such an effective match with the films lies in its sonic detailing; our attention is drawn to qualities like the dry frictive sweep of brush on snare, an intimacy of sound verging on the tactile. How beautifully this corresponds to Denis’s knack for extracting a universe of lived experience from tiny, telling gestures (director of photography Agnès Godard and editor Nelly Quettier deserve great credit here too). Both approaches begin at the micro level and build outward; this is readily apparent in the rapturous hotel scenes of Friday Night, where the color and texture of the lovers’ bodies appear as disjunctive fragments, fleetingly glimpsed as they slip in and out of the binding cover of darkness.

It’s hard to overstate the importance of music in these films, spare as they are on dialogue and exposition; it conjures an emotional orientation in lieu of otherwise absent cues. In White Material, the score signals tragedy as a foregone conclusion, while the music in Trouble Every Day takes us a long way towards understanding the film as something more than just another blood-soaked genre exercise.

Like many film scores, though, the same basic requirements a composer must abide by—brevity, simplicity, unobstrusiveness—can make for a less-than-compelling “pure” listening experience. Trouble Every Day’s music needs the film as much as the film needs it—but is this a good thing? Not if you’re listening to the CD.

The Tindersticks box has its shining moments, among them, “Room 321” (from Trouble Every Day) and its suspended silences; “Camions” (from Nénette and Boni); White Material in toto, which gets my vote for their strongest work to date. These cues, though, are mostly miniatures—nearly half of the set’s 78 tracks clock in at two minutes or less. Unless you’re Anton Webern, such brevity is surely inhibiting, diminishing its expressive potential to that of a dinner party backdrop or an interstitial for NPR. As with most film music heard without its images, we see how little these themes—and many are gorgeous—were allowed to unfold in any truly musical way. Like the donor’s heart in The Intruder, much of this material struggles to survive when removed from its original setting.

White Material

The exclusion of diegetic sound in nearly all these tracks is also unfortunate. Within those few exceptions—most notably, the yelping dogs of “Pusan Snow” (from The Intruder), and, in what I find to be the most affecting moment in the entire set, the segue from police siren into “Les cannes à pêche” (from Nénette and Boni)—there’s a sense of fullness that’s missing from much of the “purely musical” material.

We can only imagine what might have been done with additional recording to further develop these motifs, or by the creation of extended pieces using these cues as raw material- something like, say, Teo Macero’s work with Miles Davis. Something, in other words, to approach the level of the composers—Rota, Morricone, Takemitsu, Burman, and others—whose work has had a life independent from the films for which it was composed.

I hate the thought, too, that some will listen to a cue from Nénette and Boni and never see the indelibly strange sight of Boni relieving himself as he clutches a pet rabbit. And when image and music are reunited, well . . . just imagine the shock ahead for the curious Tindersticks fan acquainted with the tender swelling strings of Trouble Every Day, desiring the film from which the music came—there is just no preparation for that.