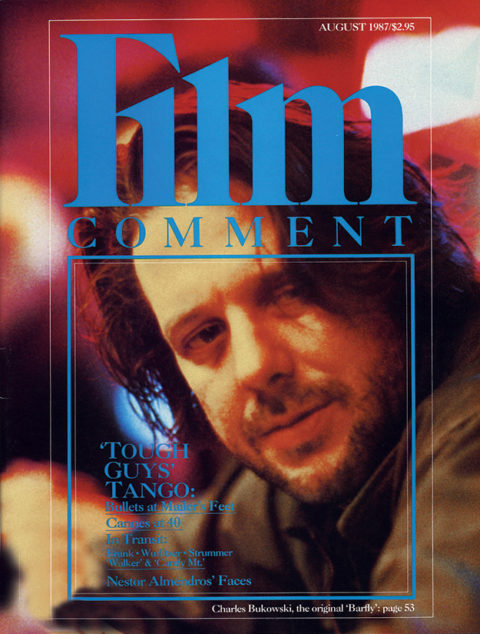

Americans are the beloved noise-makers, the unschooled and the uncut, appreciated most when at their simplest. Poet Charles Bukowski is the classic case of the American original who found his first audience abroad. In the U.S.A., particularly in his hometown of Los Angeles, he is the dirty old man, boss vizier of the sleaze-o-rama precincts of East Hollywood. Where transients slide into cheap rooms and get awakened in the middle of the night by yelling neighbors, Charles Bukowski is the presiding boozehound laureate. The very image of Bukowski’s celebrated kisser—the brooding skull, the lived-in face, the delicacy behind the scar tissue—has been enough to consign him to the bohemian backwaters of American letters.

But the powerful simplicity of his prose—he writes like a man in a slow-motion haze—translates easily into other languages. His first novel, Post Office (1971), eventually sold 75,000 copies at home—but 500,000 worldwide. Bukowski gained American recognition with his books Erections, Ejaculations, Exhibitions and General Tales of Ordinary Madness (1972), Factotum (1975), and Women (1978), but nothing like the cult prestige he received in Europe, and he continued to live in relative obscurity and sorry circumstances into his late fifties. His American publisher, John Martin of Black Sparrow, sees an earlier parallel in the career of Henry Miller, another prophet without honor in his own land.

Bukowski is, in all ways, a man of the street, a MeatPoet, an anti-academic, one who never earned his rent check as a guest professor. He could pick up a few hundred bucks for a college reading, but felt brutalized by the experience.

His cult reputation in Europe continued to grow into the late Seventies, culminating in a notorious French TV talk show appearance. “It was the number one program in the ratings,” recalls Barbet Schroeder, who directed Barfly from Bukowski’s script. “Even the best writers train like racehorses for this show. More than 50 percent of France saw Bukowski getting drunk on television and saw this Johnny Carson-like superhero, Pivot, being totally thrown off balance for the first time in history. Bukowski was so drunk, he put his hand on the knee of a woman writer there. [Pivot] told the guards, ‘Take him out, take him out.’” The next morning, Bukowski’s books were completely sold out, and the man himself was greeted and cheered on every street corner.

Schroeder (More, The Valley, Maitresse) first read Bukowski while filming the documentary Koko the Talking Gorilla. Another earthy man of international background (born in Teheran of German parents), he saw in Bukowski a soul brother, a modern-day Diogenes, cynical and naked and puking on the carpets of the Athenian rich. In 1979, he paid the poet $20,000 to write a screenplay.

As a writer who grew up in Los Angeles, Bukowski naturally detested and distrusted the movie industry. Living in squalor, though, he had to pay attention to the money. But what really persuaded him was another of Schroeder’s documentaries, General Idi Amin Dada. Schroeder clearly was a man who instinctively sought out the unexpected.

It took Schroeder seven years to get Barfly going. During that time, another Bukowski story was made into a movie, Tales of Ordinary Madness, directed by Marco Ferreri (La Grande Bouffe) and starring Ben Gazzara and Susan Tyrell. The movie was made without Bukowski’s participation. He hated it. Barfly, which stars Mickey Rourke and Faye Dunaway playing lovers who prefer life at the bottom, premiered at Cannes in may and was an unexpected hit of the festival. Schroeder vowed that he would not change a word of Bukowski’s script without getting permission; he seems to have stuck by that promise.

Schroeder’s own frustrations during that seven-year wait were so vast that he took to hauling a video camera down to Bukowski’s house and taping the man’s bumptious, surreal monologues. The resultant Charles Bukowski Tapes (available from Lagoon Video, P.O. BOX 5730, Santa Monica, CA 90405) is a straight look at the artist talking. Every great artist should have such a record. Schroeder thinks, however, that not every great artist has the enormous physical presence of Bukowski. “The only other person I filmed in a documentary that has as much presence, where 90 percent of what you film is good, was Idi Amin Dada.”

There is a quality shared by Idi Amin and Bukowski—and Schroeder confirms this. Both men will say anything; the self-censoring mechanism has been dismantled. Like the deposed Ugandan dictator, Charles Bukowski does not give a damn what he says or who he says it to. Visitors to his house are advised to take heed of this. You never know when the liquored-up Bukowski will be spoiling for a fight.

Bukowski and Schroeder

The first note about Bukowski, however, is that he has departed his old deadbeat East Hollywood streets for the safe little dockside community of San Pedro. Behind a mighty garden is his large white house. It has a spare, faintly Japanese feel, and it’s kept neat. Parked in front is his pride-and-joy symbol, a blue BMW.

When I arrived one night, Bukowski (friends call him Hank) and his wife Linda, an aspiring actress in her early thirties and former owner of a health food restaurant, were watching a tape of the Hagler-Leonard fight. He pointed to his Barfly T-shirt and said, “How do you like that? Self-promotion.”

In his comfy old moccasins, he shuffled to the sofa and opened a bottle of respectable California red. Then he sat there on the sofa’s edge, as still and significant as a massive white Buddha. He insisted that the interview would not start until we had killed at least one bottle. He was enough of a showman to know when the good stuff would start coming. Linda kept pace with him. She had her opinions and she gave as good as she got. Bukowski tended to stare into the haze, his eyes narrowed to wry, gazing slits. He has a pleasing voice, younger and jollier than it should be, and his scarred face is, up close, rather pink and soft. When a hard-boiled surge ignites him, he takes on a comical gruffness.

He is, in his 66th year, a man of compulsions. He can’t stay away from the racetrack. He smokes ratty little Indian cigarettes, Mangalore Ganeesh Beedies, that won’t stay lit for three puffs, so he spends the entire night lighting and re-lighting these roachlike stubs. The only thing that has brought him this far is that he also has a compulsion to work: every few days he goes up to the attic, turns on the classical music station, opens the bottle, and writes. He’s written over 40 books this way. On other nights, he just drinks. They were working on the third bottle by the time I went out the door at 3 A.M.—C.H.

You don’t like movies, do you?

No. Linda will say, “Let’s go to a movie.” And I’ll say, “Oh, Christ,” It’s embarrassing to see a movie. I feel gypped, sitting there with all these people. It is a good excuse to buy some popcorn and a Dr. Pepper. You’d never eat popcorn sitting at home.

Did you always feel that way?

When I was a kid in the Depression, when you’re eleven years old, Buck Rodgers looks pretty good to you. Even Tarzan. The Cary Grants and all that, we used to yawn through that. Still do. Movies—nothing much has occurred through all the decades.

Want me to name them? One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest, Elephant Man, Eraserhead, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?—that’s a classic. Kurosawa and those great battle scenes. And all those great samurai films where guys are chopping heads off.

The first movie that had an impact on me, that made me cry, was All Quiet on the Western Front. The scene with the butterfly got me. The truce had been signed, the Armistice. Trying to catch that butterfly, God, it really affected me. The way the build-up was, you knew it was going to happen and yet you said, “Maybe it won’t happen.” Then I saw it three years ago, and oh no, before it even started, I knew what would happen, and I started crying. I was a young kid when I saw it. Lew Ayres, with those bright eyes. “We must defend the Fatherland!” And they all turn to Lew. “Should we go?” “Yes.”

Linda: You liked Chinatown.

CB: Okaaay, so you didn’t waste the evening, but you don’t go around thinking, like you do with Eraserhead, “Oh, what’s happening here?” We got cable TV here, and the first thing we switched on happened to be Eraserhead. I said, “What’s this?” I didn’t know what it was. It was so great. I said, “Oh, this cable TV has opened up a whole new world. We’re gonna be sitting in front of this thing for centuries. What next?” So starting with Eraserhead we sit here, click, click, click—nothing.

Movies are an alternate dream state for people. Maybe you like the one you’re already in?

I feel mobbed, I feel diluted, I feel mugged by watching a movie. I feel they take something away from me. They’ve chewed up my auras and mutilated me. I want to mutilate my own auras at my behest, I don’t want to sit in front of a screen and do it.

Have you known people who’ve worked in movies?

Fortunately, I have not. Oh, people have come by, even before this shit started. Godard. Werner Herzog. James Woods—before he became big time. We met a lot of these people through Barbet. Harry Dean Stanton. Sean Penn and Madonna. Eliot Gould. They all come by.

Harry Dean’s a strange fellow. He doesn’t put on much of a hot-shot front. He just sits around depressed. And I make him more depressed. I say, “Harry, for Chrissakes, it’s not so bad.” When you’re feeling bad and someone says that, you only feel worse.

Barbet just showed up one day. Said he wanted to make a film about my life. He kinda talked me into it. I was very reluctant, because I don’t like film. I don’t like actors, I don’t like directors, I don’t like Hollywood. I just don’t like it. He laid a little cash on the table—not a great deal, but some. So I typed it out. That was seven years ago.

I started writing dirty stories and I ended up writing a fucking screenplay. And now I have Godard, Werner Herzog, and Sean Penn coming by. The little girl next door says, “Oh, Hank, is it true that Madonna came to see you?” I said yeah. “But why would Madonna come to see you?”

Sean [Penn] wanted Dennis Hopper to direct, and I wanted Barbet. Because Barbet put seven years into this. They gave Barbet a pretty lush offer, to be a producer, a whole deal. But he said, “No! I must direct this myself.”

LB: It was so funny. I came in the door and it was Hank and Barbet and Sean and Dennis sitting here. They’d all been drinking, except Dennis, who was all cleaned up. He had a gold medallion and a polyester jersey, and it really offended them. It was really funny, because he was really nervous to be around Hank, as it turned out.

CB: One time something was said, and it wasn’t quite funny, and he just threw his head back and laughed. The laugher was pretty false, I thought. The chains kept bouncing up and down, and he kept laughing. After he was gone, Barbet said, “You hear that fucking laugh, did you see all those chains?” I said, “Yeeesss.”

He got all excited and phoned where his will is. “In case I die, Dennis Hopper is never to be allowed to direct Barfly. Anyone else in the world but Dennis Hopper.”

And I don’t think Dennis was all that bad. He’s probably a damn good director. But I guess Dennis once told Barbet that he couldn’t direct traffic.

LB: In the middle of Ma Maison, in front of everybody, they were having this debate and it turned into an argument and Dennis screamed at him, “You can’t direct traffic!” That was years ago. He was kind of wild then.

CB: People remember that stuff. But he’s had a nice comeback. I guess he’s been in bigger pits of hell than I have.

Sean Penn.

He seems very withdrawn, delicate. He waits before he speaks. He tells interesting stories. He used to bring his bodyguard. His bodyguard was better than Sean. The bodyguard was a funny guy, telling stories about how he beat guys up. He’d roll on the rug describing fights.

LB: Sean came here not as a celebrity, but to visit Hank. It was the other way around. He wasn’t the celebrity, he came here in awe. He had a different temperament completely. He wasn’t a celebrity, he was a person. He was very vulnerable, he was real.

CB: He was also looking for a part in Barfly. The only bad—[things about Penn] I’ve seen is what I’ve read. I haven’t seen it personally. Except one time I made a small remark about Madonna which was not flattering. He was sitting right next to me. He started standing up. I said [low and tough]: “Hey, Sean, sit down, you know I can take you, don’t be silly.” He sat back down.

I think Sean was much better when he was younger. An innocent madness just flaring out. I liked him better earlier. The longer hair, he was thinner, and his eyes were wild.

Barfly

What was your first reaction to Mickey Rourke?

I hadn’t met Mickey, but I’d heard many stories about him. I thought, “This guy will be a complete prick. I better not get drunk and take a swing at him. I better watch my drinking. I could ruin the whole movie by getting into it with this kid and being completely honest.”

But he was so nice. His eyes were good. Even one time Linda and I were walking on to the set, they weren’t shooting. Mickey was being interviewed, they had the cameras on him. He saw me and said, “Hey Hank, c’mere! Help me!” They got me on, talking.

I think we just liked each other. One time Linda and I were sitting in the bar when they were shooting. We were getting plastered, which was a mistake. The bar was still open while they were shooting around the corner. I saw Mickey and I said, “Hey, c’mon, have a drink.” He said, “No, I can’t. We neeeeed you!” Just like a little boy. He needed me to watch him act.

The guy was great. He really became this barfly. He added his own dimension, which at first I thought, this is awful, he’s overdoing it. But as the shooting went on, I saw he’d done the right thing. He’d created a very strange, fantastic, loveable character. When it comes out, I can see all sorts of kids acting like him. All the kids are gonna start drinking!

How was Faye Dunaway?

I saw her in Bonnie & Clyde. She filled the role. Period. She wasn’t exceptional. She wasn’t bad. She just filled the role. [To the microphone.] Sorry to say this, Faye, you want me to lie? I just made an enemy. That’s one of my problems—I can’t lie.

Is it pretty much as you wrote it?

Yeah. Barbet wrote in the contract that nothing could be changed without my permission. It’s pretty good for a screenwriter. Never heard of that before.

Barbet has a lot of respect for what I write. He even phones from the set when I’m not there and says the actors can’t say the line. You know, sometimes you write a line and it looks good on paper, but with the human voice it doesn’t work. So I give him another line. So we’ve been working together that way. It’s right down to what I wrote. If the writing’s good, you’ve got a good chance for a good movie.

He’s been improving the pace. The first cut I saw was very slow in the beginning. It’s marvelous what they can do to pep it up just by cutting here and there—you get a sense of rhythm. A certain zip develops, you can feel it, like a horse galloping. When you get these deadly pauses, you can just sense them. We saw that in the beginning; it just bothered me. “This is so labored.” They’d just put everything together, with no music.

He’s really pushing it. He sent the Cannes people a rough cut, and they liked that. The last I heard, they had seven rooms with people working on it in each one, and he’s running from one to the other.

The whole movie was shot in six weeks. And what’s the cutting time, four weeks? We’re working under the mad whip here, but instead of detracting, it seems to be giving it more jazz.

Did you get some screenplays and study the form?

Hell no. [Disgusted.] Well, you know, it’s just dialogue, people walking around. You don’t have to study that. I can’t see taking instruction on anything…

I guess it was because I had a tough childhood, with my father telling me what to do all the time. So if anybody tells me, “This is how you do this…” I don’t ever like to be told how you do this. I just want to do it, whatever has to be done. If somebody says, “You do it like this,” I immediately cut off and go cold. And it extends to trivial areas of life….Things must come through joy and wanting to do them. I don’t like instruction; I can’t handle it.

I guess a twisted childhood has fucked me up. But that’s the way I am, so I’ll go with it. I’m afraid if I correct myself, I’ll fuck myself up. I don’t want to be cured of what I am.

My father was born in Pasadena. He went to Germany and met my mother—he was in the army of occupation, you see. They got married and brought me back. I was here at the age of three. My father was very strict—he wouldn’t let me play with the other kids, beat me, all that.

When I went to grammar school I was a sissy because I couldn’t catch a ball, I didn’t know how to react to the other kids. But I wasn’t a true sissy. You know, all the stuff was there, but I hadn’t learned how to do things. So the other sissies gathered with me. It was awful, I detested them. I wasn’t a true sissy.

Finally, as the years went on, I evolved, all the way from being a sissy to the toughest guy in school. That’s really going up the ladder. I remember in college, sitting there, this kid comes up to me. He remembered me from grammar school. “Jesus, man, you used to be a sissy. What happened?” “Go away, leave me alone.” So that was a great transformation. It’s something you have to overcome.

If the promise of screenplay fortunes had come at a more pressing time, might it have been a more distracting lure?

It did come at a pressing time, and that’s just why I did it. Because I was living in a dive and just barely getting by. I really hadn’t been lucky until three or four years ago. And I’m not rich. And I’m not poor. Neither are you, right? So the money looked good. And I think they got a bargain—for what they paid for.

And if the movie’s a success, you’ll participate?

It will be a success, because Mickey did a great job of acting. He really did it.

Had you ever given a thought as to who might play your life story?

No, because I never thought anyone would do my life story. I did think, well, maybe I’ll die sometime and somebody will take a shot at it. Usually they fuck it up. There was a thing about Kerouac on TV the other night—it was awful. You can’t watch it too long. This guy smiling. We were switching back and forth between F. Scott and Kerouac. We finally had to stop watching both of them.

Most writers’ lives are more interesting than what they write. Mine is both. They meet on an equal plane.

I just wrote it and said it was in the hands of God, they’ll fuck it up. I didn’t expect a great deal. So I was ready for when they fucked it up. Fortunately, because of Barbet Schroeder’s directing and Mickey Rourke’s acting and all the barflies—they took them right out of the bar—they got a great cast and it worked. It’s going to be a fine movie. It might even win a fucking Academy Award for Mickey. For screenwriter? Well, maybe. I’ll get a tuxedo.

What was the period you drew on for the screenplay?

Actually, it was two periods and I melded them together. When I lived in Philadelphia, I was a barfly. I was about 25, 24, 26, it gets kinda mixed up.

I liked to fight—thought I was a tough guy. I drank and I fought. My means of existence…I don’t know how I ever made it. The drinks were free, people bought me drinks. I was more or less the bar entertainer, the clown. It was just a place to go every day. I’d go in at five every day; it opened officially at seven, but the bartender let me in, and I’d [have] two hours [of] free drinks. Whisky. So I was ready when the door opened. Then he’d say, “Sorry, Hank. Seven o’clock. Can’t give you any more drinks.” I’d say that I’d do what I can. I was off to a good start, with two hours of whiskey. Then I’d get mostly beers. I’d run errands for sandwiches, get mostly beat up. I’d sit there till 2 A.M., go back to my room, then I’d be back at 5 A.M. Two and a half hours of sleep. I guess when you’re drunk you’re kind of asleep anyway. You’re resting up.

I’d go home and there’d be a bottle of wine there. I’d drink half of that and go to sleep. And I wasn’t eating.

You must have had a hell of a constitution.

I did have, yeah. I finally ended up in a hospital ten years later.

Did you have a lot of energy?

No. Just the energy to lift a glass. I was hiding out. I didn’t know what else to do. This bar back east was a lively bar. It wasn’t a common bar. There were characters in there. There was a feeling. There was ugliness, there was dullness and stupidity. But there was also a certain gleeful high pitch you could feel there. Else I wouldn’t have stayed.

I did about three years there, left, came back, did another three years. Then I came back to L.A. and worked Alvarado Street, the bars up and down there. Met the ladies—if you want to call them that.

This is kind of a mixture of two areas, L.A. and Philadelphia, melded together. Which may be cheating, but it’s supposed to be fictional anyway, right? Must have been around 1946.

It seems that all the good old scum bars are disappearing. In those days, Alvarado Street was still white. And you could just duck inside and get 86’d in one bar and then move right down ten paces and there’s another bar to walk into.

I’ve gone into bars with deadwood people and an absolute deadwood feeling. You have one drink and you want to get the hell out of there so fast. But this bar was a lively hole in the sky.

The first day I walked in, I got hooked. I just got into town. I walked out of my room—it was about two in the afternoon. I walked in and said, “Give me a bottle of beer.” Picked it up and a bottle came flying through the air, right past my head. People just keep on talking! Guy next to me turned around and said, “Hey you sonofabitch, you do that again and I’m gonna knock your goddamn head off.” Then came another bottle flew past. “I told you, you sonofabitch.” Then there’s a big fiiiiight. Everybody went out in the back.

I said, “God, what a jolly, lovely place. I’m going to stay here.” So I kept waiting for a repeat of that first lovely afternoon. I waited three years and it didn’t happen. I had to make it happen. I took over.

I finally left. I said, “That first afternoon is never going to recur.” I was sucked in. It was right after the war was over.

Barbet Schroeder got a worldly crew. The German cameraman, Robby Müller, anyway, looks like a gnome from the underworld.

Robby did Paris, Texas, and he’s got a camera. I saw the first dailies, and I had to tell him, “I’m not even a film man, but as I watched it the first thing that came to mind was that you meant it.” You can sense that he’s grasping the totality of the event.

This didn’t inspire you to write another screenplay?

No. Because I know that this was a special group. You write another one and you’ve got a lot of bitching people…

I wouldn’t know what to write about. I couldn’t just sit down and make something up. Because it wouldn’t work. You can’t do that.

What about “The Horseplayer”?

There’s a possibility there. [Lights up.] I’ve never covered the horseplayer, how the disease started.

Disease, did you say?

Everything’s a disease, because it’s going to kill you, one way or another. Whether you do it or you don’t, it’s going to kill you. What am I saying? Does that make sense? Let it ride…

LB: They optioned his novel Women.

CB: [Menahem] Golan’s after it now. He’s all excited. Ran up to me and kissed me. I pointed to Barbet and said, “Here’s your man, kiss him.” He smelled money there.

The Bukowski Tapes

What did you think of The Bukowski Tapes?

I liked them the first time I saw them. Second time, it was just an old drunk talking away. It’s very hard to see them all at once. It’s like reading a book of poetry straight through. It’s jarring.

I had a guilt complex because I never thought Barbet would get Barfly off the ground. So he thought he’d just get me drunk and talk for video cameras. We got lucky. I made the tapes out of guilt. I wrote a screenplay I didn’t want to write.

Have you ever seen where the medium of film has been given over to the poetic impulse very successfully?

“The poetic impulse.” That’s a dirty word to me. It’s a misused word. You can’t use the word anymore, because people have belabored it so much. It’s like the word “love”; they just pounded it into the ground. “Poetic,” “love,” you just can’t use them and feel safe. Too make fakes have trod up and down the path using those words. You try to find another word.

Cocteau once said that an artist’s work is his alibi.

Sounds good. He made some movies, didn’t he? Heads popping out of couches and all that. I saw them at the art theater in Greenwich Village when I was starving. Totally artsy and artificial.

Today the popular perception of drunkenness has changed considerably from when you were young.

You mean, they kind of fear it? Make it something evil?

It is viewed, widely, as an illness.

They’re probably right. But think of all the ill people who don’t drink at all, who are just dull within themselves. All they need is a glass of water. There are people and then there are people. A lot of damn fools drink. In fact, most of them do. There are always exceptions within the rule, as they say. This bar was an exception. And I think I was an exception. I don’t think I was a standard dull drunk.

We had a roaring time. And we’d be sitting there, eight guys. And suddenly somebody would make a statement, a sentence. And it would glue everything we were doing together. It would fit the outside world in—just a flick of a thing, then we’d smile and go back to our drinking. Say nothing. It was an honorable place, with a high sense of honor, and it was intelligent. Strangely intelligent. Those minds were quick. But given up on life. They weren’t in it, but they knew something.

I got a screenplay out of it and never thought I would, sitting there.

Then there was The Iceman Cometh.

Yeah, I read that. Now there’s a philosophical bar. But it’s grim and dank and near the edges of hell. These old farts, man, they’re awful people. It’s grimy, dull. I liked some of O’Neill’s stuff—it wasn’t so much the story of a bar as some philosophical bullshit thing. People don’t act like that in bars. Yeah, O’Neill, I liked a lot of his stuff when I was young. He was a drunk. I like the bit where people become the masks they put on. “Lockhead Becomes Elektra,” something like that.

You know, I’ve read everything, but I forget it. I used to read 12 books a week. I’ve read the whole fucking library.

What are you reading this week?

I haven’t read anything for ten years. I can’t read. You put it in my hand, it drops out. Doesn’t do me any good. I like the National Enquirer and the Herald Examiner, that’s about it. I’m serious.

You once wrote a regular column in the L.A. Free Press, and in a column on how to pick the ponies you said, “Having talent but no follow-through is worse than having no talent at all.”

I was thinking of horses when I said that, but I guess it applies everywhere.

Have you been following through?

So far. With minor fame. That’s what I’ve got now. Minor fame is bad.

What is the effect of fame on a writer?

Depends on your age, brainpower, and your guts. I think if you’re old enough, you have a better chance to overcome what they put on you. If you’re a genius at 22 and the babes come around, the drinks… How old was Dylan Thomas when he died, 34? It can come too soon. It can never come too late, I guess. I think I’m safe.

I get letters from women who want to show their naked bodies. “I’m 19 years old and I want to be your secretary. I’ll keep your house and I won’t bother you at all. I just want to be around.” I get some strange letters. I trash them. Even before Linda and I got together.

Nothing’s free. There’s always problems, there’s always tragedy, madness, bullshit. There’s a big trap waiting with all these dollies who send letters about what they’re going to do for me. They just want you to walk into it and put the clamp on you. No way. So I’ll answer, “Good God, girl, give it to a young man who deserves it and leave me alone. And drive safely.” Never hear from them again…

As Ezra said, “Do your W-O-R-K.” That’s where the vigor comes from, the creative fucking process. Puts dance in the bones. Like I said, if I don’t write for a week, I get sick. I can’t walk, I get dizzy, I lay in bed, I puke. Get up in the morning and gag. I’ve got to type. If you chopped my hands off, I’d type with my feet. So I’ve never written for money; I’ve written just because of an imbecilic urge.

Even when you were writing for porno magazines?

That was for the rent. [Grins.] That was sicker. I didn’t have the urge, but I did it. I enjoyed that. I would write a good story that I liked, but I would find an excuse to throw in a sex scene right in the middle of the story. It seemed to work. It was okay.

Some guys manage to get ahold of their creative energy when they’re young, some guys wait a while.

I waited a long, long while. At the age of 50, I was still in the post office, stacking letters. I was still working. I was not a writer. I decided to quit and become a writer. When I went to resign, the lady in the post office said [clucks tongue reprovingly]. I always remember that. It was my last day on the job. One of the clerks said, “I don’t know if he’s going to make it, but the old man sure has a lot of guts.”

Old? I didn’t feel old. You’re just walking around in your body, you don’t feel any age. When you get old, people say things, but there’s no difference. So that was a big blow. I said, “Oh shit, what have I done?” The landlady said I was crazy. But she was nice, and sometimes she’d leave a big dinner out for me. And every other night I’d go down and drink with them all night long and sing all night. In between I wrote my own stuff. Dirty stories. That was on DeLongpre.

I’m 66 now. That was in 1970. I guess I got lucky late.

LB: Do you think that’s the best way?

CB: Hell yes, because then you’ve got all the background to reach into and then write things about. The trouble is, with most people and the eight-hour job, when you want to reach, there’s nothing to reach. I was lucky because I didn’t believe in the job.

In Europe now you are recognized on the streets. Does this get in the way?

All a drunk wants to do is have an excuse to get drunk. So if your celebrity is an excuse to get drunk, you get drunk.

I write when I’m drunk. Take away the typewriter and I’m a drunk without a typewriter. Could be some goodness left over, or some charm or some bullshit. It’s all mixed together.

One of the hurtful things about fame is that you play more to a past image than a future image.

Exactly. Especially a writer. The only thing that amounts to a writer is the next line you’re going to write down. All past things don’t mean shit. If you can’t write that next line, you as a person are dead. It’s only the next line, this line that’s coming as the typewriter spins, that’s the magic, that’s the roaring, that’s the beauty. It’s the only thing that beats death. The next line. If it’s a good one, of course. [Grins.] That bothers me a lot. No it doesn’t. Consider that the next line could be dead. But we’re not our own best critics, are we? I imagine a lot of guys keep typing while saying, “This stuff is great.”

It may be madness, but I feel I’m still growing. It’s like somebody trying to push out of the top of my head. Working, working, working… A good feeling, man. The gods are good to me. They haven’t always been good to me, but lately they’ve been kind to me.

[Raises toast.] Here’s to my father, who made me the way I am. He beat the shit out of me. After my father, everything was easy.