By Ela Bittencourt in the May-June 2020 Issue

Blood on Their Hands: Luis Ospina

Colombian class warrior Luis Ospina blazed a revolutionary trail through Latin American cinema with subversive genre and documentary works

The transgressive social visions of Bacurau and Parasite may have helped prepare us for the chaos and iniquity of the COVID-19 era, but long before those films of class warfare, there was Luis Ospina. In Latin America, the revolution had a blueprint in the brazen works of the late Colombian director, who made over 30 films energized with the snap of genre and the spirit of revolt. Ospina was significantly younger than most directors of the Pan-American Cinema Novo—e.g., Brazil’s Glauber Rocha, Argentina’s Fernando Solanas, Cuba’s Julio García Espinosa—but such generational and aesthetic distance suited Ospina just fine. Born in Cali, Colombia, in 1949, and educated in Los Angeles in the ’60s and ’70s, he was a self-styled cinematic punk rocker. While at UCLA, Ospina devoured experimental cinema and American B-movies in equal measure. In the same vein as Quentin Tarantino and Kleber Mendonça Filho and Juliano Dornelles, Ospina imbibed Hollywood and then adapted it to his quixotic tastes.

For Ospina, this meant bending genre in every possible way. His documentary-manifesto film, The Vampires of Poverty (1977), was an outrageous hybrid that criticized the left for presenting illusions of doing good while sensationalizing poverty. The 29-minute short follows a crew of reporters (played by Ospina’s friends, including co-screenwriter Carlos Mayolo) as they drive through Cali, bossing around and then choreographing its poor for their crude flash-exposés, generally acting “like two fucking vampires,” as one character says. Ospina’s actual vampire movie, Pure Blood (1982)—particularly apt for our grim pandemic times, when the social fabric frays along class divides—was a savage satire in which the spoiled, selfish rich cannibalize the vulnerable poor. At the film’s center, a mortally ill old sugar tycoon requires constant blood transfusions, and his cocaine-addicted, ruthless henchmen kidnap and murder youngsters in poor neighborhoods for fresh supplies. Yet Ospina also makes the criminals appear bungling and laughable, mixing elements of horror, exploitation, and comedy. After a long hiatus from fiction films, Ospina’s Breath of Life (1999) was both an homage to film noir and a languid melodrama that drew partly on real events—and like Pure Blood, centered on nefarious behavior by the powerful and the wealthy. A Paper Tiger (2008), on the other hand, though it masqueraded as a documentary, was a delicious, wicked fiction in the spirit of Zelig, about a famous and ubiquitous Colombian artist who in fact never existed.

Only a handful of Ospina’s features can be referred to as conventional documentary: Andrés Caicedo: A Few Good Friends (1986), a portrait of his comrade, the writer Caicedo; and It All Started at the End (2015). The latter builds out from Ospina’s multiple cancer treatments and his illness’s recurrence, and then documents Cali’s vibrant, tight-knit arts community that originated in the 1970s. Even though the film now comes across as his testament—he died from the illness in September 2019—the forever-experimenting director made it in the spirit of an ongoing conversation rather than a final word on his career or epoch. Nevertheless, the ghosts of the departed weigh heavily on the film, particularly in the recorded conversations relating to the suicide of the brilliant Caicedo, at the early age of 25, which left a permanent mark on his entire cohort; and later, the deterioration and death of Ospina’s lifetime collaborator, Carlos Mayolo (deceased in 2007). The film’s bittersweet tone also reflects the disappointment of many artists close to Ospina who saw the heady revolutionary dreams and egalitarian ideals of the 1970s unfulfilled.

I sat down to speak with Ospina over two days in the fall of 2018, while he was being celebrated at the Doclisboa Film Festival with a retrospective and a programming carte blanche slate (he showed Bruce Conner’s films, among others). Ospina was making plans, metamorphosing again—this time into a video artist—and he mentioned that, at times, he felt with video like he was shooting a sci-fi documentary. A perennial outsider, he was reluctant to enshrine himself as a persona or a movement. Which seems ironic, of course, because when he co-wrote the 1978 “Poverty-Porn Manifesto” with Mayolo, he put into words the anger that to this day Latin American filmmakers express at seeing their countries’ misery exploited, and exported abroad. His ethical concern with representation on screen, not only in documentary but cinema as a whole, fuels the preoccupations of directors like Mendonça and Dornelles. And the idea that took hold of Caliwood back in the 1970s—that provincial stories are, in fact, universal, and each province is its own world—resonates strongly today.

Ospina was also influential in Latin America as a film critic, and as the founder and director of the Cali International Film Festival (FICCALI), launched in 2009. Yet he remains largely unknown in the West, though retrospectives at Doclisboa and on the streaming site MUBI may change that. During that Lisbon tribute, Ospina told me that he’d suffered from insomnia since his early editing years. Of late, he endured it by YouTube-binging on film noir—a genre he’d loved since his days studying filmmaking at UCLA, when he attended a series programmed by Paul Schrader. That’s where we began our conversation, in which Ospina reaffirmed his dedication to helping viewers see urgent social issues in a new light.

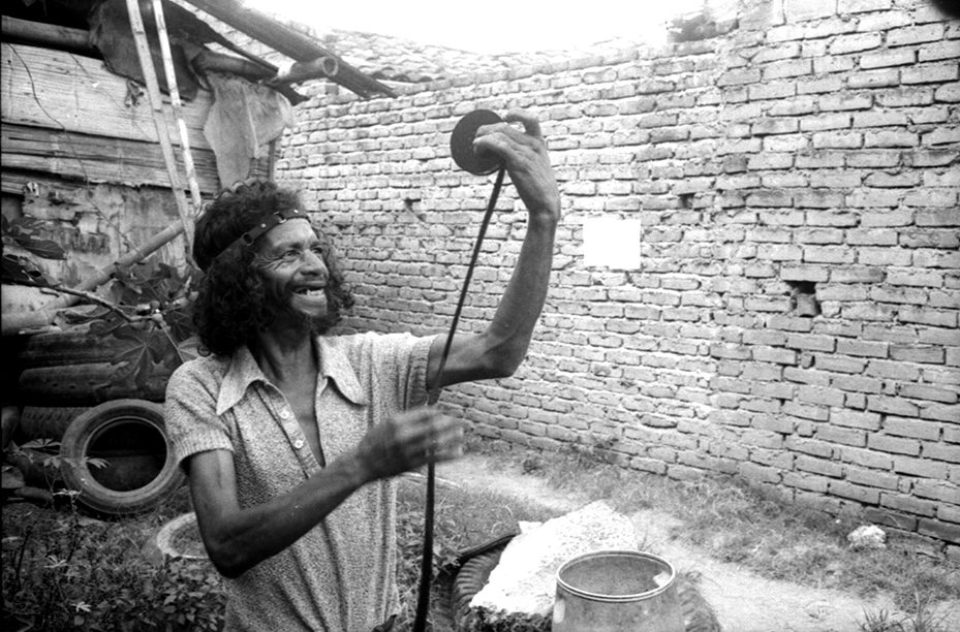

Pure Blood (Courtesy of the DocLisboa Film Festival)

From the May-June 2020 Issue

Also in this issue

When did you fall in love with film noir?

I became addicted to it while I was a student at UCLA. It got to be my favorite genre, because it’s very pessimistic, and my work is very pessimistic. Film noir was practically invented by Hollywood, but it translates to any country. You have film noir made in France, Mexico, Brazil, Argentina, but in Colombia back then nobody had made a film noir.

There’s an enjoyment and imperfection in B-movies that’s very attractive. In Cali, we were very interested in art-house movies, but there was another side to us, the B- and C-movies side. I saw the Hammer Dracula when I was 9 or 10, and then all the sequels. The Night of the Living Dead [which I saw during the Vietnam War] taught me that the horror genre could be adapted to the social or political situation of your own country. And of course, Dracula is a metaphor of power. You have the Count who lives up there in the castle, and literally lives off the blood of his subjects. The power of one body over another—that’s vampirism. You bite somebody and he becomes part of you.

In our group, the writer Andrés Caicedo [who also edited Ojo al cine, Cali’s movie magazine] was a great admirer of gothic literature, horror, Lovecraft, and especially vampire films. And when I lived in L.A., I shared an apartment with a Mexican friend who had a television set. Shows would come on late at night, and we would concentrate on this little screen. I saw wonderful things like Curse of the Undead. It’s the only vampire western I’ve seen. I used to like westerns as a kid.

You made the first Colombian vampire film, Pure Blood.

Yes. I based it on urban myths and a little bit on Howard Hughes—a character that lives secluded, watches movies, has long hair, and long fingernails. [Laughs] Mine was a different type of vampire film in that instead of fangs, they have hypodermic needles. I think I’d seen George A. Romero’s Martin, a modern vampire film with needles. After that, vampire films had different versions, like Abel Ferrara’s The Addiction, where vampires are junkies and the blood is like a drug.

When I was growing up, there was a series of child rapes and murders in Cali. Dead bodies were found in barren lands two blocks from my house. It was the first dead body I had ever seen. Sometimes the body had a hole in the heart. People invented a story that a famous rich man who owned a movie theater or hotel was responsible for these crimes. He lived in a strange house and drank young boys’ blood. In the movie, I made the victims white and male—to combine the Dracula myth with a famous homophobic hate crime [that happened when I was an adolescent]. I made Dracula a sugarcane tycoon, because after the Cuban revolution people needed sugar, and Cali was one of the best places to find it. It became the only crop that made profits. Plus it’s white—the cocaine business was starting, so there’s the white powder. The workers were mostly black, which you see when they are cutting sugarcane.

The madman who’s then made a scapegoat is also black. You hit on all the taboos: classism, racism, sexism, homophobia.

Another film that made me think a lot about genre and form was Georges Franju’s Eyes Without a Face. I really like that film; it’s one of my favorites. There are elements of it in Pure Blood, when they go out at night and kidnap boys. There’s also that wonderful song by Billy Idol. [Laughs]

Cheaply made genre films, such as horror or porn comedies (pornochanchadas), were big in some Latin American countries in the 1970s. Was there a similar low-end genre push in Colombia?

No, because there was no competition in Colombia. During the 1950s, hardly any movies got made. Films came from Hollywood, or Mexican co-productions, but there really wasn’t a film movement or industry. There was no financing or subsidies for films, either, so we made our [Caliwood] group. Now critics and historians [call] what we started “Tropical Gothic,” which is what the Brazilians were actually doing before us. There was a whole movement.

Mayolo knew the Colombian writer Álvaro Mutis, who lived in Mexico for many years and was a good friend of Buñuel’s. In a conversation, Buñuel said it was very difficult to make a gothic film in the tropics. Álvaro said, “I’ll write you a story that proves it [is possible].” So he wrote “The Mansion of Araucaima.” Buñuel read it and wanted to film it—he even cast it, but it was never made. Many years later the Colombian Film Fund bought the rights to the story and commissioned Mayolo, because we were the only ones interested in genre. I believe that’s where the term came from. Now people say that Pure Blood was the first Tropical Gothic film.

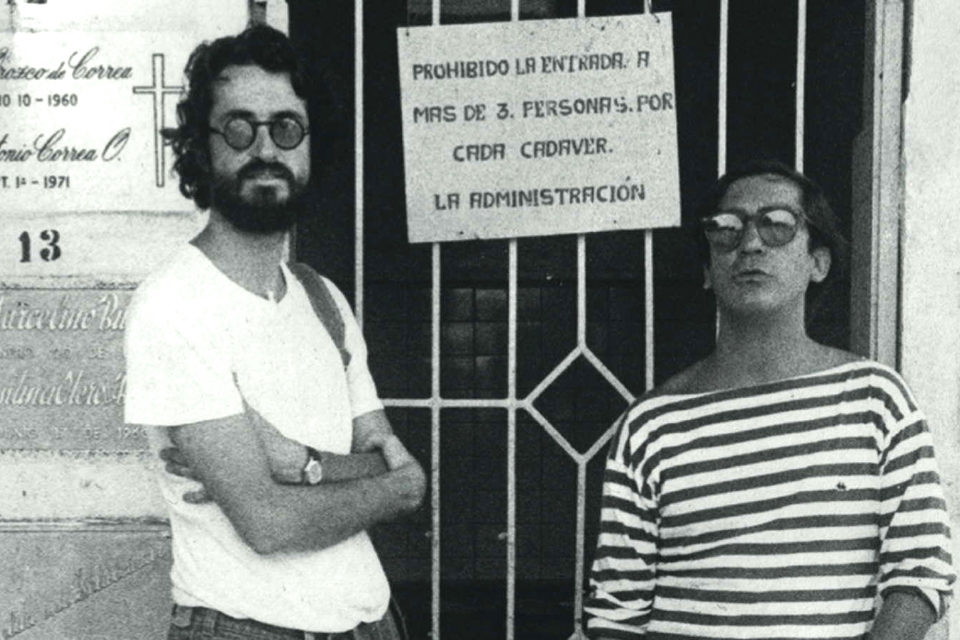

The Vampires of Poverty (Courtesy of the DocLisboa Film Festival)

You shot The Vampires of Poverty with Mayolo, and co-wrote with him the Poverty-Porn Manifesto. How did your collaboration come about?

I met Mayolo when I was only 7 years old. My family’s house was destroyed by a famous explosion in the 1950s, during the military dictatorship. Twelve trucks of gunpowder were parked in the red-light district of Cali. Suddenly, they exploded—nobody knows why—and it killed a lot of people. Fifteen or 20 blocks had to evacuate, including ours. So we moved to my grandmother’s house. Then I met Mayolo, and we started going to the movies together.

Mayolo started making industrial shorts and advertising in the mid-’60s. When I returned to Colombia for a vacation, in 1971, we decided to make together the documentary short, Listen, Look! [during the Pan-American Games in Cali]. We were also in a film club. We had a camera and a tape recorder. That’s how we started working. I was very shy and he had a very explosive personality, very quick, very funny. We complemented each other well, and shared the same visual sense and humor. We made documentaries and even a short fiction film together [Angelita and Miguel Ángel, 1971]. Then in 1977, we made The Vampires of Poverty. At that time, the easiest way to make money was just to go out into the street and shoot films about poverty, with a voiceover. A lot of miserabilist films were starting to be made. We were reacting to that, because we thought poverty was becoming a type of merchandise.

Did you come across American pseudo-documentaries, such as Symbiopsychotaxiplasm, when you were in Los Angeles?

No. I remember others, but later. At that time nobody spoke of making documentaries. The only thing similar to our film in Latin American documentary was Arthur Omar’s Triste Trópico in 1974. We decided to make The Vampires of Poverty as a provocation. That’s why, when you start watching it, you don’t know what the fuck it’s about. [You may ask], “Should I laugh? Should I be against it?“ Sometimes you have to use the arms of the enemy to destroy the enemy—like an antidote in medicine. You inoculate to eradicate the disease. It’s a therapeutic film [in this sense]. It gradually flows into fiction, because the middle part is all scripted, but at the end, it again becomes a documentary.

At Doclisboa, you made a distinction between making political films versus making films politically. What did you mean by that?

One of our purposes was to make directors think about ethics before making a film, because there’s an intrinsic vampirism in cinema. You’re taking somebody’s image, and with that image and sound you can make an ideological film that is leftist or rightist or whatever. It depends on how you edit. Film is not objective and documentary is not all true. Especially [when done] by leftist filmmakers. I don’t believe that you can use film to change the world or for a cause, to support an ideology.

Was there any state support for your cinema in Colombia?

I have always considered myself non-mainstream, underground. I’ve made the films that I wanted to make without concessions, mostly because I’ve produced them myself. I have rarely gotten money, [from the government or] from other countries. Only for Breath of Life, from France. And my movies are very low-budget. But I’ve decided to quit feature filmmaking. Breath of Life was my farewell to fiction films, and it’s the only film I’ve made where I wasn’t the original scriptwriter. The screenplay was written by my brother, Sebastián. The government had stopped financing the film industry for 10 years. And then, 10 years later, they had just one prize, for best screenplay. My brother got that prize. He didn’t want to direct the film, so he proposed it to me. I immediately said “of course,” because it was a film noir. I hadn’t made a feature fiction film in 18 years. I was living in a rented house in Cali. Most of my friends had left, and I decided to go to Bogotá and make this film. I adapted the screenplay and I researched film noir a lot.

It All Started at the End (Courtesy of the DocLisboa Film Festival)

Which films did you research?

I showed [my team] parts of Jacques Tourneur’s Out of the Past, which is for me the best film noir ever made. There was a scene in Abraham Polonsky’s Force of Evil. Some Mexican film noir. Even things like Psycho. Film noir wasn’t about the American dream, but what had happened to that American dream: the femme fatale, paranoia, corruption, very dark sides of the human soul. After the Second World War, the attitude changed. Those were the most political films made in Hollywood.

Film noir was perfect for Colombia, because we have a pessimistic outlook, political corruption, a high degree of impunity, and, of course, the drug trade. In the ’80s, when the film takes place, the drug traffickers were becoming a strong and deadly force. My fiction films are always based on reality. On the one hand, there was the tragedy of Armero, where a mudslide following a volcano’s eruption destroyed a whole city. Thirty thousand people were killed. My brother, who acts in Breath of Life, fell in love with a young woman. We finished shooting the film, and then he heard that she had died in the landslide. So the film is an homage. One of the things that attracted me to it is that I had never shot a love story. Here I find this story of a woman who has several lovers. I had never filmed a kiss in my life. The film is a flashback within a flashback within a flashback, which is very normal in film noir. In Colombia, films were always very straight narratives—no jumping back and forth in time. In Breath of Life, the scenes played in the present are in black and white, and the flashback goes to [color] film stock.

After that, you quit.

I never felt at home working within the hierarchy of fiction feature films. When Breath of Life was finished, the distributors didn’t like it. They shelved it for about a year, and then released it in the worst fashion possible. It was a financial disaster. I lost a lot of money. My brother lost an apartment. I prefer to do documentaries. The technology changed at that time: video became an alternative in the mid-’80s, and then digital. I decided I didn’t feel comfortable, because fiction film is like a military operation. So I never attempted to make another [narrative] film. Between Pure Blood and Breath of Life, I wrote a screenplay with my friend, [Sandro] Romero, because I always wanted to make a very dark comedy. It was almost made.

It must be bittersweet for Pure Blood and Breath of Life to have a second life at festivals.

When I made Pure Blood, I started to hate the film. But as time passed, I noticed that it had an underground circulation with VHS, and sort of became a cult film. The closest I’ve gotten to making fiction after that is with A Paper Tiger.

Collage from A Paper Tiger (Courtesy of the DocLisboa Film Festival)

What are the circumstances behind its wild web of inventions?

Some of my projects become portraits of generations, and I wanted to make A Paper Tiger about my generation, the 1960s: utopia, totalitarian ideas, and how all that came to a bad end. And, of course, it was a pretext for talking about the relationship between politics and art. The film couldn’t have been made before the fall of the Berlin Wall, because many of its participants were militants with very strong leftist, Marxist leanings—[Communist] Party members. After the fall, they were willing to lie, to have fun and to laugh at their own ideas. A Paper Tiger is a little bit ahead of its time, [more in tune with] what’s happening right now with post-truth. I wanted to put into question the narrative devices that you use to tell the truth and to tell a lie—they’re the same. If you say, “This is a shot of Ukraine and this man is Grushenko,” we believe that. We are used to believing what’s said. In fact, that scene wasn’t shot in Ukraine; it was shot in New York. That man’s name isn’t Grushenko. Grushenko was Woody Allen’s character in Love and Death.

The film’s main character, Pedro Manrique Figueroa, was invented by my nephew in 1996. When he was in art school, he and his friends were asked to write about their favorite artist, so they invented [one]. I made the film in 2007, and I liked very much the idea of inventing an artist. So I decided to make a mockumentary, with all the traditional features of a documentary: archival material, interviews, historical documents. I looked for people who had a lot of credibility with Ukrainian culture: historians, filmmakers, ex-militants, artists. I would describe the character to them and ask: “Do you know somebody like this?” They’d say, “Oh yes, I knew someone in the 1960s.” Everybody had an anecdote about somebody they knew. I then told them to change the names and improvise stories, and I would invent a context in which they could have met my character. Then I always tried to find a conflict.

It feels like one of those postmodern Latin American novels.

Roberto Bolaño’s 2666. In fact, when I was making the film, people would always talk to me about that novel. I read it afterward. I also knew of the Spanish writer Max Aub, who emigrated to Mexico. He invented an artist called Jusep Torres Campalans, saying this painter was a friend of Picasso’s. I did a lot of research in the Colombian film archives. A film about a collage artist has to be a collage in and of itself. For me that was easy, because many of my later films are collages.

It All Started at the End includes videos from your hospital bed, pre- and post-surgery, plus some made with friends, cooking and chatting at dinners.

I am what you call a hoarder. All of my life, especially since I decided I’d be a filmmaker, I’ve kept everything. Letters, photographs, souvenirs. We hoarders keep things because they might be useful. I don’t know for what. When I made the last film, I finally knew why I kept all this shit. I went through all my archives and started classifying them. Not only about myself but about my friends, about the city. It finally had a purpose.

Ela Bittencourt works as a critic and curator in the U.S. and Brazil and consults for a number of international film festivals. She also runs the film site Lyssaria.