By Nicolas Rapold in the July-August 2019 Issue

Lonesome Trails

Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time... in Hollywood yearns for the liberating powers of storytelling and finds flickers of life in painted sunsets and broken dreams

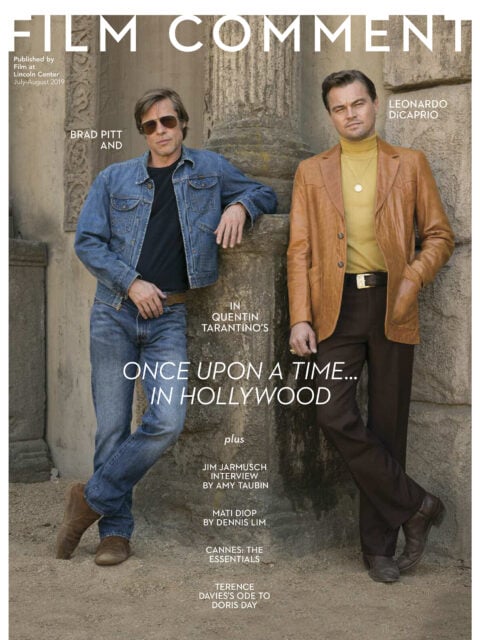

More than any fairy tale, or a Sergio Leone film, the title of Quentin Tarantino’s ninth stand-alone feature suggests an elaborate yarn that might take a while to tell. Not so very elaborate but indeed a tall tale of sorts, Once Upon a Time... in Hollywood is set in a familiar fantasyland and era—the perennially mythologized late ’60s, with its dashing of hopes, fall from grace, bummer wake-up from a beautiful dream. Or, as focused through the lens of Tarantino’s characters: at the apparent end of the road for a TV actor named Rick Dalton, and by extension his stunt double Cliff Booth. Beginning its timeline in February 1969, Once Upon a Time... in Hollywood introduces us to Rick (Leonardo DiCaprio) side by side with Cliff (Brad Pitt), the two explaining their trade in a black-and-white behind-the-scenes interview on an anonymous Western set. Rick plays cowboys, Cliff plays Rick on horses and in mid-air; both enjoy making up fun stuff for our entertainment.

From the July-August 2019 Issue

Also in this issue

What follows surprised many at the ballyhooed premiere in Cannes this past May, and not because somebody then blows someone’s head off (which, just to clarify, does not occur). Something stranger, in fact: Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood settles into a loose-limbed, sunny buddy routine with an undercurrent of nerves, before paths begin to diverge. Rick anxiously takes a gig playing a Western villain, with Cliff as his rock-steady support system but also wandering off on his own as whatever you call the laid-back stand-in to a potential has-been. And for a third and vital strand (as ever in Tarantino’s long-game loop-back storytelling), there’s the “real” figure of Sharon Tate (Margot Robbie) and her husband, shit-hot director Roman Polanski (Rafal Zawierucha), zooming around town, hanging out, being desirable. That despite the small matter of the gruesome Manson Family murders somewhere in there on the historical record…

Even with that on everyone’s minds, Tarantino does not drive the film forward with the hand-rubbing glee over narrative tension that has been his stock-in-trade (and that failed him utterly in his most recent, turgid feature, The Hateful Eight, which intriguingly Nick Pinkerton has described as “a stubbornly, defiantly misanthropic movie, a film that brings back the spirit of Hollywood in the mid-’60s”). Far from it: Rick embraces his new role as a saloon heavy and boyishly gets his groove back; Cliff tries to mind his own business with (an even more Western-like) manly charisma and code of decency; and the apparently doomed Tate takes unabashed pleasure in being on the brink of making it—through all of which, Tarantino nurtures into being something unexpectedly touching, even sweet. The filmmaker remains invested in the outsider or struggling criminal—a transmutation of 1970s antiheroes into the language of movie types—and his heart here lies with these underdogs, the TV actor who was barely making do and the talented stunt double who might fade away.

A glib formula might describe Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood as combining the middle-ager, last-chance gambit of Jackie Brown and the lurid revisionist urge to punch up history in Inglourious Basterds. But it’s something at once mature and madly, deeply, and now less collector-ishly in love with Hollywoodland and, even more, its far-flung margins—and here, in the most artificial of settings, Tarantino achieves something genuine and heartfelt.

Margot Robbie in Once Upon a Time... in Hollywood (Quentin Tarantino, 2019)

As anticipated and speculated upon as Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood has been, isn’t this also a filmmaker who is in many ways deeply unfashionable for what we call our times? For one thing, the particular way in which Tarantino lives in and through movies seems to have receded from pop-cultural prominence, much less the mythos of a video-store-educated savant—a notion that would meet with blank stares from a generation weaned on the firehose of streaming, YouTube, and torrents. Likewise, Tarantino’s upending of high-low hierarchies and his secret-handshake references quicken fewer pulses amid a general sense of cultural amnesia (or indifference)—not to mention a landscape where burgeoning television offerings elicit wild critical praise and loving scrutiny for supercharging and elaborating within assorted genres. And most fundamentally, Tarantino’s penchant for grisly-glorious revisionism has become a non-starter for some in an era demanding more enlightened approaches to history, very nearly across the board. In the case of his latest, the filmmaker has already been put on the spot for the gender distribution of his dialogue.

That last criticism must have befuddled Tarantino, because Robbie’s Tate is so affectionately written and, with Pitt’s Cliff, surely shares the heart of the film, Rick’s hapless antics notwithstanding. Despite the apocalypse we all associate with Tate, in Hollywood’s Hollywood she is simply an actress with her life ahead of her who takes pleasure in her own work. A standout sequence, at first seemingly set up for disappointment and a cheap laugh, sees Tate stopping at a cinema where the farcical comedy The Wrecking Crew is playing, co-starring her in a klutz role. She has to introduce herself to the theater staff, but then is welcomed in; kicking up her bare feet on the chairs, she soaks in the laughter of the audience. She’s enjoying herself, in every sense; the movie’s not Tess of the d’Urbervilles—the book she buys for Polanski, in another affecting scene—but she’s making her way (as Cliff, for one, is not). Tarantino’s professional admiration is just as palpable here as it is with Rick when he finally gets going, the joy of moviemaking being another well-established aspect of the Tarantino mood.

In the eyes of DiCaprio’s Rick, of course, Tate’s already made it, by virtue of Polanski’s post–Rosemary’s Baby cool-kid status; the young couple tools around in a sports car, free as can be. Meanwhile, Rick on his first shoot in a while spends his downtime reading a Western pulp fiction about a breaker of horses, whom he describes thus before tearing up: “He’s not the best anymore. He’s coming to terms with what it’s like to become slightly more useless each day.” Rick says this to Tate’s formidable next-gen successor—an utterly self-possessed child actor (Julia Butters) he’s performing with, who’s busy reading a biography of Disney and taking no guff. Tarantino’s sympathies have always rested with working professionals, whom he has delighted in holding up for glory, whether it’s directing German TV actor Christoph Waltz to two Oscars or putting stuntwoman Zoë Bell in a leading role. And sure enough, in Rick, he sets up a scenario whereby this TV actor whose worth rests on entertaining folks with daring deeds could accomplish another spectacular one before the film is through.

Speaking of spectacle, the director’s usual sense of buildup and whiplash surprise is not where the force of this film lies. Instead it takes the unusual Tarantino tack of feeling out this moment in no great hurry, at one point skipping ahead six months—from February to the fabled August of 1969—and not hanging on Rick a dramatic arc of the falling/rising actor (though, spoiler alert, he gets to work with Sergio Corbucci, on the advice of an agent played by Al Pacino). Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood sets the scene for historical events to step in, but the constant oddly enough becomes Pitt’s Cliff, once a hothead trailed by horrible rumors, and now an affably resigned guy who shares his home with a cuddly pitbull he lingers over feeding chunks of canned food. With DiCaprio encouraged (or not needing much encouragement) to stick to the confines of playing the insecure actor, Pitt as his loyal second is allowed to shine with a positive sunset glow to match the warm colors of the photography (less lurid than its key art). Not seeming to mind his circumstances, the star, at his best in years and hitting a wondrous stride, settles so comfortably into the role of a supportive shadow that you do believe Cliff might prefer it.

Leonardo DiCaprio in Once Upon A Time... In Hollywood (Quentin Tarantino, 2019)

It’s Cliff who walks into the lion’s den, the almost too-ready-for-essayizing Spahn Ranch: the former location for some down-at-heel shoots, and home to the most lurid B-movie of them all, that of Charles Manson and his followers. It’s a curdled alternate world where Cliff discovers owner and past acquaintance George Spahn (an ornery, apparently immortal Bruce Dern), blind but living in a state of contentment and denial about his tenants. Cliff ’s visit is a refraction of the high-profile intersections that Manson would indeed have with a starry milieu he could not access. (The same frustration lights one fuse in Mary Harron’s Charlie Says: a visit by an unimpressed music agent leaves Manson unrecognized, and seething.) Cliff has to lay down some law at the ranch and leave, but the wishful simplicity of the heroism doesn’t detract from the strength of a film shaped and scaled and paced with largely unostentatious aplomb (and hopefully not to be adversely altered by the rumored potential of a pre-release edit). In its knitting together of Rick/Cliff/Tate and letting Cliff come into his own as a character, Tarantino works at a high level of pure narrative satisfaction, patient craft over showmanship, recalling the confident and moving achievement of Jackie Brown.

Where then does that leave the so far unspoiled ending? And is there a touch of Rick-like anxiety in Tarantino’s public hand-wringing over fellow movie-lovers ruining his creative mojo? The injunction turns critics into Tarantino characters, talking around and around to delay the next twist, and in so doing building it up. Well, by way of beginning… it’s usually said that history repeats itself. And certainly in our current so-called reality, it feels that way, with the country locked in a political time warp replaying the cynical antagonisms of (newly inaugurated in 1969) Nixon’s revanchist runs, not to mention the Hobermanian nightmare of having a bad actor for a president (another one). And frankly, the more I’ve thought about the world Tarantino creates—and re-creates—in the first two hours of Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood, the less significant the knowledge of the film’s ending has felt, even with its true-to-Tarantino cage match of fact and fiction.

After all, the spirit behind the film is that the spoiler already happened—out there. And the irony is that the expected Manson reckoning and how it affects our good buddies on screen neither ruins the film nor surpasses the warmth that came before. The inevitable climax has nothing on the wistful feeling that lingers when the dust clears. And within minutes, it’s just another story to tell the neighbors.

Nicolas Rapold is the editor-in-chief of Film Comment and hosts The Film Comment Podcast.