Sundance 2023: How Does It Feel?

This article appeared in the February 2, 2023 edition of The Film Comment Letter, our free weekly newsletter featuring original film criticism and writing. Sign up for the Letter here.

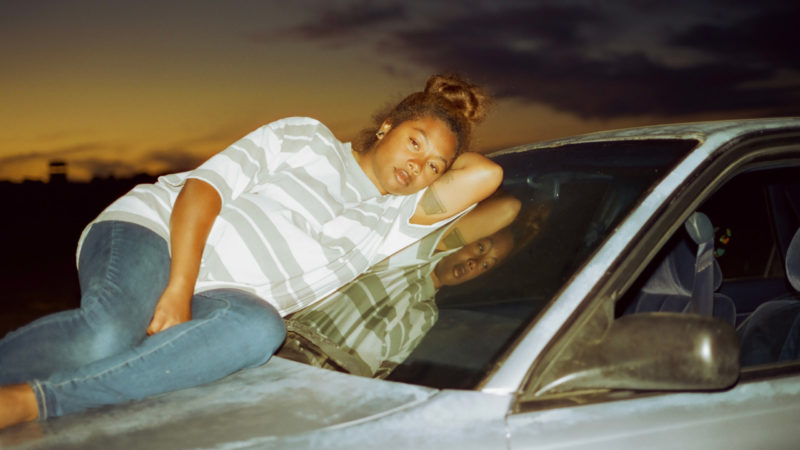

Earth Mama (Savanah Leaf, 2023). Courtesy of Sundance Institute.

Savanah Leaf’s Earth Mama opens with a woman facing the camera, saying defiantly: “I don’t care if y’all don’t care if I do make it. It’s my journey; it’s nobody else’s journey. Nobody is going to walk with these shoes I got on my feet.” Bright and early on my second day in freezing Park City, this scene felt like an invigorating omen. The Sundance Film Festival can often seem overly beholden to ideas of cinema as an “empathy machine,” where form is subordinate to “story” and “character” (two much-cited buzzwords of the festival and its labs), and demands of relatability subsume pricklier human complexities. In films about social and cultural traumas—particularly Black women’s traumas—the emphasis on empathy can even feel insidious, implicitly furthering the idea that one can only care about people whom one can either relate to or pity.

With its opening flourish, Leaf’s debut feature—about a young Black mother who struggles to reclaim custody of her kids from the foster care system in San Francisco—announces with bracing frankness that it intends to pander to neither our sympathy nor some generic idea of empathy. That scene, as we eventually learn, is from a support group for women trying to win back their kids from the state; it’s one of the many classes and appointments that 24-year-old Gia (rapper Tia Nomore in a tremendous acting debut) is mandated to attend to prove to child protective services that she deserves to parent her two young children. Shot head-on, with the directness of nonfiction, these scenes gently stretch the contours of the film beyond the insular, ever-tightening world of its lead, reminding us that her story is not hers alone. At one point, the camera follows Gia out of a class but then lingers behind for a few seconds on another attendee—a woman we’ve seen before but know little about—as she breaks into quiet tears. The film abounds in such moments—of witnessing and listening, if not understanding or knowing.

Importantly, we never learn Gia’s own story; she declines to speak at these sessions, much to the chagrin of her best friend, who insists that not sharing—not performing, as it were—will make it harder for her to convince her caseworkers that she’s making progress. It’s a radical gesture on the part of Leaf, too, to deny us the why and the how of Gia’s predicament, and instead simply confront us with the now—with the freighted choices and decisions Gia navigates every single day. She visits her young daughter and son once a week, under supervision, while preparing to give birth to a third child. She begins contemplating the difficult prospect of giving up her soon-to-be-born baby for adoption, wanting to save the child from the fate of its siblings. In another of the film’s profound gestures of listening, Gia asks the men who loaf around her neighborhood about their childhoods. Framed against the bright, faux-tropical backgrounds of the photo studio where Gia works, they speak vulnerably about the scars of the foster system, tears escaping the cracks in their tough facades. Earth Mama is a story of precarity—Gia barely has money to pay her phone bills or buy presents for her kids, and in one gutting scene, we see her steal diapers—but it’s told with a languor and an insistence on beauty that reengineers how we often perceive destitution. Cinematographer Jody Lee Lipes shoots the film in gorgeous 16mm, in natural light and lambent colors, so that every character and setting glows—not with the kind of stylized, set-dressed sheen that might sand down the film’s realities, but with the genuine, generous love with which Leaf and her team regard their subjects.

Raven Jackson’s All Dirt Roads Taste of Salt also resists parsing or explication, but it submerges you deep in its rhythms; watching it is like bathing in an ocean whose limits you cannot see. Jackson is a poet and photographer, and her debut feature gets as close to poetry as any recent narrative film I’ve seen. The film traces the life of a Black woman, Mack, in 1970s and ’80s Mississippi, sinuating rapturously through her childhood, adolescence, and young adulthood, all of which unfold within intimate cocoons of family and country life. (She is played as a girl by Kaylee Nicole Johnson, and in later years by Charleen McClure.) The tale unfurls in nonlinear fashion, with vignettes sequenced idiosyncratically, following an internal meter rather than any recognizable notion of plot structure. Dramatic events in Mack’s life are submerged or elided, so we only learn of them after the fact or in oblique ways—a funeral follows a mesmerizing dance scene, as if the death that intervened has been swallowed up by memory; a series of close-ups show us the faces of seated churchgoers, then gives way to a shot of two intertwined hands, before the frame widens to reveal that we are witnessing a wedding. Shot in symphonic proximity to nature—to the dirt that nourishes life—and emphasizing both its spiritual and practical significance in Southern Black life, this is a film of whispers and textures, accumulating a story of a place as well as a person. All Dirt Roads has been compared to the work of Julie Dash, Terrence Malick, Barry Jenkins (who is one of the producers), and others, yet the film never feels derivative or forced in its experimentalism; it impresses as a work of fiercely personal intuition, one that invites us into a world—and a formal logic—entirely its own.

Hewing to a more familiar narrative framework, but eschewing empathic understanding to a similar extent, was Eileen, the new film by William Oldroyd (Lady Macbeth), adapted from Ottessa Moshfegh’s same-named 2015 novel and co-written by the author and her husband, Luke Goebel. The title character (played here by Thomasin McKenzie) is a mightily repressed 24-year-old prison secretary in suburban Massachusetts in the 1960s, who lives with her abusive, alcoholic, ex-cop father and entertains twisted erotic fantasies behind a plain, even dull exterior. On paper, she might seem like another Sundance archetype: the “unlikable” woman, quirky, tortured, and violent in all the right (and often overly justified) ways. Yet the accomplishment of Oldroyd and the writers is in making Eileen not unlikable so much as unknowable, a cipher around whom they slowly swirl a story that is delicious in its pulpiness and thrilling in its dark surprises. The book is narrated by Eileen, her monologue enthralling with its flat affect and caprice. The film adapts Eileen’s inner life into a quiet, ambient fury of sound and image—grubby interiors (shot by Ari Wegner) streaked with even grubbier shadows; luscious colors that evoke both sex and blood; scenes that fade in and out of each other like smoke, occasionally interrupted by brittle bursts of violence. The film’s catalyzing incident is the arrival of a stylish, chain-smoking, Harvard-educated prison psychologist, Rebecca (Anne Hathaway), who allures and excites Eileen. But what initially seems like a Carol-esque story of desire threatening to burst through manicured seams swerves into a seedy and terrifying tale of vengeance—one whose portrait of abuse is no less eviscerating for the bottled-up wildness of its heroine, played by McKenzie with a miraculous, morbid sense of mystery.

Lastly, a word on Last Things, the new film by Deborah Stratman that premiered in the much-reduced New Frontier section of Sundance 2023. Talk about rejecting empathy: Stratman’s haunting, iridescent work of science-nonfiction actively decenters the human perspective, narrating the history and the speculative future of the universe with rocks as its protagonists. The idea that minerals evolve over time—and preserve records of our world’s many lives—drives Stratman’s inquiry, which, as is often the case with her work, is at once dryly analytical, politically urgent, and cinematically riveting. The framing narrative is culled from texts including Clarice Lispector’s The Hour of the Star and works by J.H. Rosny, the pen name for the Boex brothers, who wrote a series of novels in the late 1800s in which the future looks a lot like the prehistoric past, evacuated of anthropomorphic life and taken over by “inorganic” aliens. These excerpts are read by the filmmaker Valérie Massadian (Nana, Milla) in a voiceover that instantly brought to my mind Chris Marker’s La Jetée (1962)—another dystopian tale in which past and future blur together, and humans, for all their hubris, seem impotent. Other bits of voiceover come from interviews with Marcia Bjørnerud, a geoscientist who offers analyses of mineral memories and the “polytemporal worldview” that rocks open up. The stars of the show, though, are the many images of rocks, crystals, particles, plants, and other earthly objects that Stratman weaves throughout, and which sparkle and glow and hum like otherworldly objects, producing a kind of awe that urges us to look differently, obliquely, at the world around us. When the film gets to its epilogue (its post-credits scene, if you will) of break-dancers in Brazil, you might find yourself gazing at the concrete percussed by their feet, thinking of the songs held within.

Devika Girish is the Co-Deputy Editor of Film Comment Magazine.