Interview: Lois Patiño

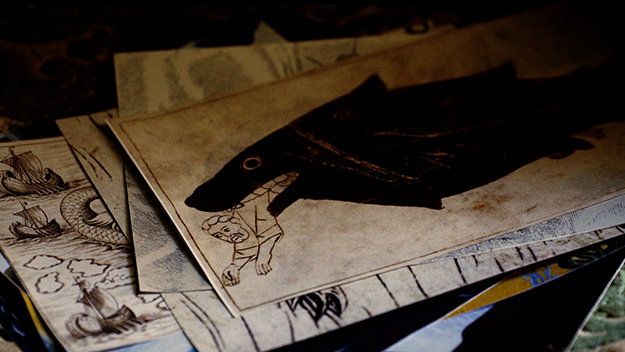

Images from Red Moon Tide (Lois Patiño, 2020)

Seven years after his award-winning debut Coast of Death (2013), Spanish filmmaker Lois Patiño returns to the same location in northwest Galicia for his second feature Red Moon Tide, a belated follow-up and quasi-companion piece that expands on the mytho-historical undercurrents coursing beneath the former film’s eerily placid surfaces. Defined by jutting rock formations and swelling seasides, Costa da Morte is a region of both immense beauty and extreme brutality: named for the many shipwrecks that have occurred along its turbulent shoreline, it’s a setting especially conducive to folklore and storytelling. Inspired by the experiences of a local diver who rescued numerous bodies from shipwrecks, Patiño depicts a community in the throes of mystery and mourning: the diver, Rubio, has gone missing, while the bodies of those lost at sea appear fated to remain in a kind of oceanic purgatory. Populated by people both living and dead, real and imagined, it’s a landscape caught between past and present, with ghostly figures draped in white sheets emerging from the memories of their loved ones, who speak in meditative voiceover about the myths and local legends that haunt the region—including an ominous red moon able to summon a beast from the watery depths below. Known primarily for a series of radically aestheticized short films that turn otherwise familiar landscapes into uniquely alien environments, Patiño here strikes upon an intoxicating form of hybrid narrative that brings his creative and cultural interests to equally expressive heights.

Following Red Moon Tide’s premiere in the Forum section at the 70th Berlinale, Patiño and I sat down to discuss the film’s lengthy gestation, the myths at the heart of Galician culture, and the unexpected discoveries that shaped the film’s form along the way.

Maybe we can start with a more theoretical or conceptual question. When beginning a project, do you find yourself starting with a location or a theme/subject first? I’m just curious, since so much of your work is about landscape, if that’s your starting point or if it sometimes begins with a specific subject rather than a setting?

I think in general the main goal in my work is to try to reflect on a spiritual relationship with the space. It’s like Freud’s notion of the “oceanic feeling,” the idea of feeling or being dissolved, through a revelatory or spiritual moment, in the energy of a landscape. That’s an experience that I try to offer to the viewer through contemplation. I think that’s the ultimate goal in my approach.

From another perspective, in every project I try to look for and explore new cinematic forms, new ways of cinematic language. In Red Moon Tide I’m working with the idea of people paralyzed in a specific space, which is something I also explored in my previous films Night Without Distance (2015) and Fajr (2016). Conceptually and narratively I’m looking at what can be expressed through people paralyzed in space, as a way to explore the different experiences of time. In this film, people are immobile but have an introspective attitude. So they are out of time, because they are experiencing a kind of inner time. I’m interested in working with this idea of inner and external time and, in this film, with reality and myth. And this doubles again with regard to temporality: a chronological time—reality versus the mixed time of myth or legend.

Another typical starting point for me is to reflect on the identity of the landscape, how it is built through the layers of overlapping history and myths. An interesting definition of landscape is this one that says: landscape is strata of time condensed in an image—but also, reciprocally, how certain landscapes evoke certain myths and legends. There aren’t the same myths in the desert as there are here at the coast with a dangerous sea. The identity of a landscape arises from a constant back-and-forth between the people and the landscape. So my work usually starts from a mix of these two explorations: a reflection on the cultural identity of a landscape and the exploration of time through a new cinematic language.

At what point did you come to the story of this real-life diver, Rubio de Camelle? Did the paralyzed people idea exist before you discovered the story?

I discovered the story a couple of weeks before the shooting.

Oh, really? So you had already conceptualized the film?

Yes. We were already preparing the shooting and my production designer told me about this person, Rubio, and his story. So the day after I went looking for him in the little town where he lives and he was cleaning fish in the port with a knife. Rubio is very well known in the town and the people, of course, like him a lot because of his braveness: he rescued more than 30 corpses of shipwrecked people there. He knows the ocean currents very well. His story connects with many of the concepts that we wanted to explore.

In terms of legends and the evocation of myths, the film centers on death and the sea—all the myths that can be evoked from these themes. His story connects with that a lot. Another concept that was becoming more important as we went along was the grieving and mourning process. Rubio helps a lot of families gain closure, because, in terms of legend, when a sailor disappears at sea, he remains in limbo. He cannot go to the afterlife: alma en pena (suffering soul) is what it’s called. So Rubio not only rescued the corpses of these sailors, but also their souls.

In the film there were two aspects of the grieving process that interested me: experiencing the physical absence of the corpse, at which point closure is impossible, and then the presence of ghosts that people see of their friends and family members, that also denies that closure. The phantom is part of this mourning process.

So the proximity of where you planned to shoot and the town where you found Rubio was purely coincidental?

It was a coincidence but I began developing the idea for the film in 2013, very soon after my previous feature, Coast of Death. So I’ve been working on it for a long time. The place in Red Moon Tide is the same as Coast of Death, which was more focused on the landscape’s anthropological connection with reality. But in Red Moon Tide, we’re focusing on the other side. We focus on the same place but from a mythological point of view.

During the process, several ideas or images appeared, like the sea monster, which at the beginning was not going to be included. I was invited to Mexico to make a video art project with underwater images and it was a very spiritual experience for me to dive with a whale shark, which you can’t find in my homeland of Galicia. So I thought that if one of these animals could come here confused, it would be seen as a monster.

In Red Moon Tide, I wanted to reflect on how a legend and myth is built. I used this choral voice of people from the village talking about the monster, some of them contradictory, because the myth is an undefined story—one without a precise limit—so this multiplicity of voices helps to build that. You have two or three elements that are fixed, but the rest of the legend can adopt multiple narratives. It’s not a straight, uniform story.

As in most of legends, the starting point of the myth is a real story. Our legend starts from the real Rubio’s story, then we also have a sea monster that is a whale shark seen by a scared diver, a rock with a weird form… All are real elements in which we project a magic and legendary view.

In this film I had a clear cinematic concept and subject to reflect on, but the story was changing with every discovery life brought to me. So it was changing constantly. I like the Heraclitus sentence, “You have to expect the unexpected or you won’t recognize it when it comes.” So I try to be as open as I can, because I’m not the same filmmaker as I was when I first started on the project. Cinema itself isn’t at the same point either. So I think it’s good that the process is alive.

How does this approach relate to the writing process, particularly since you came to the story of Rubio so late? Do you write in a traditional scripted form, or are you mostly working with treatments? Red Moon Tide feels more “written” than most of your other films, as least as far as the amount of voiceover and dialogue.

At the beginning it was going to be much more of a documentary. I recorded many interviews with people from the village, asking about phantoms that they saw and the rituals with witches that are very alive in this place. But the tone of the voices was not working well with the calm and meditative aspect of the images. So what we did is change some of the interviews and adapt them to the tone of the film as voiceover. Not only the whispering aspect, but also the poeticism of the words, which are now quite philosophical and ambiguous in how they express these ideas of time. The dialogue is written in post-production, so I was changing it until essentially yesterday. This was a very interesting thing for me, because, as you say, I don’t usually work so much in fiction, or with story or dialogue, so finding this poetic, metaphysical level or tone was very interesting for me. In the last stage of making the film I got very deep into H.P. Lovecraft, so I eventually tried to bring the story a little towards the terror genre. It was very nice to try and explore the metaphysical terror of Lovecraft.

Here the usual order of writing-shooting-editing was different. I had more or less a structure of the story: people paralyzed, witches arrive, Rubio awakes. But all the dialogues were written during the editing process. Me and the editors decided which person could be which character, and the relationship between them. We built the legend around the images.

I’m guessing you cast both voice actors and on-screen performers—they’re not the same people?

Right. We did two castings, one for the performers during the shooting, and the other one after for the voices. This also changed a bit over time. At one point I met an anthropologist, Carmelo Lisón Tolosana, who went to Galicia in the ‘60s when all these myths were much more alive than they are now. While he was there he recorded many, many interviews and transcribed them in his books. So I read his books about Galicia and the meigas—a kind of witch—and what we call Santa Compaña—the belief in a procession of phantoms—that are the most important beings of the Galician imagination. I’ve spent some time with Carmelo, who just passed away during the coronavirus crisis at 90 years-old. I asked him for those recordings of the dialogues, because I wanted to use them. It would have been interesting to have the voices of people already dead put through the bodies of the actors, to highlight both the anachronism of the myth and the spectral aspect. But back in that period, it was really expensive to have cassettes, so he recorded over all of them.

Can you talk about how your process differs when developing a feature versus a short?

Since I know getting money for a feature takes more time, I like to be working on several projects in parallel, because if one gets stuck, I can develop the other. Like right now, I’m developing a feature film with Matias Piñeiro, a short film set in Tokyo, and another film that will take place in Laos and Tanzania. So I think it’s very healthy for a filmmaker to have multiple projects in development because otherwise you can get depressed if something gets stuck at a certain stage. For me, with the short films, I try to somehow explore and better understand a certain cinematic language. With the features I go in with a better idea of what I’m exploring. With Red Moon Tide I’ve completed this exploration of a language where people are paralyzed in the landscape, just as with Coast of Death I completed my explorations around distance in landscape. One of the differences between the shorts and the features for me is that you cannot have just a conceptual or plastic idea when making a feature because, to keep the attention of the audience for a long time, you need a story. In my films I try to develop a world. In retrospect, what unites my two features is the voice—in this case the choral voice of the villagers. It’s a story built little by little and, because of the use of legends, also by contradictions.

How did you come to the idea to represent this in-between state as a person with a white sheet over their body?

I was thinking a lot about the idea of the representation of the phantom. The popular one, the one with the sheet, comes from the middle ages. They covered the dead as an act or ritual of farewell and goodbye. So when the representation of the phantom appears in the scene, it is an image of the dead body. And since in the film we’d be reflecting on the mourning process and the necessity of saying goodbye to the body, it became a part of this ritual of saying farewell and calming the phantoms. It’s all part of a ritual to get them out of limbo and to the afterlife. The three women that appear in the film need to cover the immobile bodies trapped in the landscape as a way to say goodbye. As we see in one of the scenes, as one person is speaking, a woman comes and covers him with a sheet, and suddenly his voice disappears. It’s a way to calm the spirit.

Was the idea for the three witches also something you learned or read about in relation to this culture?

There are two main images or beings in Galician imagery. One kind of witch is called meiga, that is something in-between the popular witch that we understand and someone who knows a lot about plants and nature. These meigas are very important figures that define the Galician identity. The other image is the Santa Compaña, the procession of phantoms. So as I was building this idea of legend and myth, I decided I wanted to work with very popular imagery and use almost naive figures. So in this case that meant using the popular idea and representation of the witch. For example, with Matias Piñeiro, we are working with The Tempest, the Shakespeare play, and we did a short film focusing on Sycorax, the witch in The Tempest. In both of these we’re reflecting more on the war over the image of the witch: why it was invented and put to the woman, which was basically to control them. But here, I wanted to work with the popular idea of the witch in the context of a legendary tale.

To go back to what you were saying about holding a viewer’s interest across a feature-length film: Can you talk about that as it relates to the editing and post-production process? There seems to be less visual and stylistic effects in this film than many of your shorts.

During the editing process we were working a lot because the images we have are very polysemic. Depending on what dialogue you introduce at that stage, it can change the meaning completely. You have multiple options and it was sometimes difficult to find the best one. Some cuts of the film were much more contemplative than the final one: fewer words and much more space to let the image be polysemic. But we felt the attention was going down and we were losing both the viewer’s and our own interest. In some of my other shorts, such as Night Without Distance or Fajr, the images were very different from reality, because I used various color correction techniques. Here it’s very naturalistic, with the exception of the end, where the image goes red because of the moon. Here I wanted to express the estrangement of reality through contact with a myth, and through a contrast between the image of paralyzed people and their inner voices speaking about a legend.

So, yes, the main change in terms of the editing process was taking the film from the more contemplative and silent tone of my short films, to an exploration of voices, fiction, and legend, and then, from there, trying to keep the audience’s attention and build an interesting story.

I read that one of the things that inspired the film was a quote by Álvaro Cunqueiro: “This great animal called Ocean breathes twice a day.” Can you talk about that quote, what it meant to you, how you found it, and also how you used it to apply some of these ideas visually or thematically?

One of the other things I wanted to reflect on with this film is the identity of our country, of Galicia, and one aspect that brings identity is art and the culture. I have two main references points here. One is Álvaro Cunqueiro, the writer that explored the legends and myths, and who also brought legends from other parts of the world and transposed them to Galicia. The other is Urbano Lugrís, a Galician painter whose paintings appear in the film. I wanted to connect the film with this fantastical aspect of the culture, trying to follow their path. Cunqueiro’s representation of the sea as an animal brings a lot of mystery to the ocean, and also highlights the rhythm, the “breaths,” that are the tides. The idea was to create a connection in the film between the moon and the sea and the mythical aspect of the sea. The sea here is a dangerous one—there have been a lot of shipwrecks in its history. Also, before the discoveries of the Americas, this sea was the end of the world. Many thought there was nothing beyond this ocean. It’s easy to think that part of this idea somehow remains in Galicia. It’s a mystery there. I believe in Jung’s idea of the collective unconscious, as a place where myths and dreams are built. One of the ideas behind the unconscious is that we inherit it. I think that something about the mysteries that the sea awakens in us nowadays comes from what the sea evoked centuries ago. It’s a mystery that remains very deep inside us, at an unconscious level.

Jordan Cronk is a critic and programmer based in Los Angeles. He runs Acropolis Cinema, a screening series for experimental and undistributed films, and is a member of the Los Angeles Film Critics Association.