Rotterdam 2019 Dispatch

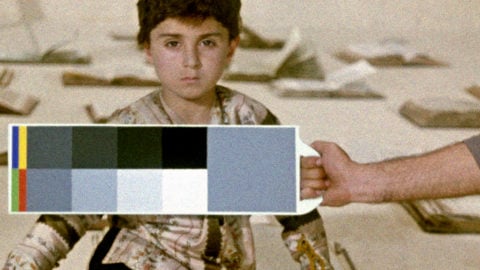

Men of Hard Skin (José Celestino Campusano, 2019)

In 2018, the International Film Festival Rotterdam hosted a near-complete retrospective of Argentine iconoclast José Celestino Campusano. For many, including your humble correspondent, it was at once an overdue introduction to a director whose work is more often rumored about than seen, and the highlight of a festival whose generous repertory programming can occasionally overshadow their main selection. Appetites sufficiently whetted, Campusano returned to Rotterdam in 2019 with a new feature, Men of Hard Skin, which, as fate would have it, was one of the best world premieres at this year’s festival, the fourth and most curatorially rich to date under artistic director Bero Beyer. A true rebel of international cinema, Campusano’s practice is in many ways emblematic of a bygone ideal of grassroots independent financing and distribution. His production company, the appropriately christened Cinebruto (Brute Cinema), through which he maintains a level of freedom and control over his projects afforded to few of his contemporaries, speaks to the methodology: autonomous, self-sufficient, uncompromising.

To say that Men of Hard Skin embodies this ideology would be an understatement. Set in a remote town in southern Buenos Aires, the film follows a teenaged boy named Ariel (Wall Javier) whose innocence is unceremoniously thrust toward maturity by a local priest with whom he’s involved in a clandestine sexual affair. Spurned briefly in the opening moments by the conflicted clergyman (he, like many in the parish, are engaged in a kind of ritual self-abasement for their sins) and encouraged by his free-thinking sister to explore his feelings, Ariel soon strikes up a relationship with a young farmhand. But as Ariel’s sexual and emotional awakening ensues, the twisted underbelly of the town begins to reveal itself; here, boys like Ariel are little more than pawns and playthings, while the urges, perversions, and prejudices of those in authority (such as Ariel’s father, a respected rancher who tries to break his son’s homosexual impulses by taking him to the local whorehouse) only perpetuate the cycle of enabling and abuse. Classically composed but caustic in temperament, Campusano’s images pop with a vibrancy and authenticity of someone intimately familiar with this milieu, and indeed the filmmaker based the story on firsthand accounts of many friends and acquaintances. The ensemble cast, meanwhile, is comprised of a variety of locals and non-actors (a Campusano trademark) whose palpably seedy and offbeat demeanors add a level deranged verisimilitude to the proceedings. The result is a troubling mix of humor and depravity, a fine line that Campusano skirts with an invigorating disregard for cinematic diplomacy

Angela’s Diaries: Two Filmmakers (Yervant Gianikian and Angela Ricci Lucchi, 2018)

Men of Hard Skin was presented at Rotterdam in the festival’s Signatures section, alongside a host of films by established directors with a trademark style or sensibility. In that regard, few inclusions in the program were as appropriate as Angela’s Diaries: Two Filmmakers, by the Italian artists Yervant Gianikian and Angela Ricci Lucchi, who, for over four decades as partners and collaborators, forged a singular and nearly unmatched creative philosophy. Following Ricci Lucchi’s passing last year (just one month after unveiling the six-screen gallery piece Journey to Russia at IFFR 2018), Gianikian began compiling decades of video footage of the couple at home and at work, as they traveled to many of the world’s most embattled countries (Armenia, Sarajevo, Turkey, the Soviet Union, etc.), gathering materials for their largely archive-based interrogations of 20th-century violence and European colonialism. But the rigorous and fiercely political nature of the duo’s practice belies the beauty and intimacy of what Gianikian has assembled here; accompanied by Gianikian’s readings of Ricci Lucchi’s travel diaries, the footage finds the pair laughing and playing, cooking and gardening, exploring and researching with an insatiable curiosity and love for life and its simple pleasures. (Seen throughout, Ricci Lucchi’s beautiful watercolor caricatures—of friends and filmmakers, world leaders and working-class locals alike—recall the range of her passions.) As Gianikian speaks his partner’s words, tenderly reflecting on their shared journey and experiences, a sense of pride in their long-standing artistic and romantic union gently fortifies the project’s achingly nostalgic undertow. It’s at once a primer on this sorely under-recognized duo and an exquisite work of personal-poetic nonfiction, quietly revealing and touching.

Winter’s Night (Jang Woojin, 2018)

As the first major international festival of the year, Rotterdam is in the unique position of hosting both world premieres and highlights from many of the previous year’s film and film-related events. Like Angela’s Diaries (which premiered as an out of competition selection in Venice), Winter’s Night, the third feature by South Korea’s Jang Woojin, has slowly gained exposure over the fall-winter festival season. Part of the 2018 Jeonju Cinema Project, Jang’s follow-up to the casually virtuoso Autumn, Autumn (2016) again examines romance and human interaction through the dual prism of fate and chance. Set in Chuncheon, on the ice-slicked grounds of the Buddhist temple of Cheongpyeongsa, Winter’s Night, much like its predecessor, follows separate plot lines over a contained period of time. Upon returning to Cheongpyeongsa to find a lost cell phone, the middle-aged Eunju (Seo Younghwa) and her husband Heungju (Yang Heungju) are soon separated, sending each on a nocturnal journey through a landscape of natural wonder and emotional uncertainty. Along the way, each character has strange and revealing encounters: Heungju with an ex-lover, to whom he drunkenly blathers about his marriage, and Eunju with a young couple whose tentative romance seems to reflect Heungju and Enju’s past selves. Unfolding with an uneasy serenity and structured around a series of snow-covered setpieces (one neon-lit enclave, set against a flowing waterfall and a patch of thin ice, is particularly striking), the film interweaves past and present, dreams and reality, memory and lived experience with the precision, delicacy, and insight of a much more seasoned filmmaker. Jang, at just 34, has quickly developed a signature all his own.

Present.Perfect. (Zhu Shengze, 2019)

Supporting and showcasing young filmmakers is one of Rotterdam’s primary objectives. Comprised of directors with less than three features to their name, the festival’s flagship section, the Tiger Competition, has in recent years brought many talented new artists a deserved bit of recognition. Shengze Zhu’s Present.Perfect., winner of this year’s Tiger Award, seems poised to parlay the prize into significant life on the festival circuit. Comprised entirely of live-streaming footage sourced from a variety of online platforms, the film brings China’s most popular (and lucrative) form of virtual interaction into a space of sociopolitical consideration and critique. From over 800 hours of footage, Zhu chose to focus on roughly a dozen subjects. Playing host to their viewers, these “anchors” act out and document all manner of interesting yet mostly inconsequential activities: a female factory worker speaking about her personal life while performing repetitive tasks; a burn victim talking about his struggle to find work and connect with others; a wheelchair-bound model interacting with her fans; a young man performing dance numbers in a public park; a bored construction worker goofing off on the job; and an amputee making the most of his condition as a street performer. Compared to Zhu’s previous feature, the elegantly composed observational epic Another Year (2017), Present.Perfect. can at a glance seem slight or haphazard, but the same curiosity and engagement with contemporary Chinese culture that sustained her previous film is here not only accounted for but approached in a pointedly political manner. Like many forms of entertainment, Chinese censors continue to shut down and silence live-stream sites and personalities, many from marginal or otherwise disenfranchised communities. “I use live-streaming to find someone to talk to,” says one anchor in a candid bit of commentary. So too, it seems, do millions of others. With genuine empathy, Present.Perfect. gives voice to a small cross section of these individuals.

Again Once Again (Romina Paula, 2019)

On balance the Tiger Competition offered one of its stronger showings in a few years, with Special Jury Award winner Take Me Somewhere Nice, from Bosnia’s Ena Sendijarević, and the wonderfully titled Nona. If They Soak Me, I’ll Burn Them, from Chile’s Camila José Donoso, putting unique spins, respectively, on both the coming-of-age narrative and the small-town political allegory. But perhaps the best new film I saw at Rotterdam (and without a doubt the best debut feature, though it didn’t compete for the Tiger Award) was Again Once Again, by Argentine actress, playwright, and theater director Romina Paula. Best known to Stateside audiences as an actress (she’s a frequent collaborator of Matías Piñeiro and Santiago Mitre), Paula puts her skill as a writer and conductor of actors, as well as her own delicate presence in front of the camera, on full display in this most personal of projects. Playing a fictionalized version of herself, Paula acts opposite her real mother and four year-old son Ramón. Separated from her husband and staying temporarily with her mom in Buenos Aires, Paula is at crossroads (or, as she says, stuck in “perpetual crises”), both as a mother herself and as a woman whose adult life has slowly usurped her youth. While back home, she reconnects with friends, reconsiders her relationship, tentatively explores new sexual avenues, and works part-time as a German tutor. Subtly mixing elements of documentary and fiction, the film plays on memory and nostalgia (often in the form of home video footage and the occasional first-person monologue) without betraying Paula’s uncertain future. Much like life, it’s comprised of small moments and unassuming interactions that, by the end, accumulate into something far greater. Introducing the film, Paula made a humble but telling differentiation in her approach, one that encapsulates the modest charms of this auspicious debut and, in turn, might offer inspiration for future Rotterdam hopefuls: “I’m not a filmmaker. I just made a film.”

Jordan Cronk is a critic and programmer based in Los Angeles. He runs Acropolis Cinema, a screening series for experimental and undistributed films, and is co-director of the Locarno in Los Angeles film festival.