TCM Diary: The Wild Boys of Wellman

Wild Boys of the Road

This fall, the name William A. Wellman will briefly flit across screens in multiplexes worldwide, as it tends to reappear every time A Star Is Born is remade. It remains to be seen how much of Wellman’s 1937 original with Janet Gaynor and Frederic March will be recognizable in Bradley Cooper’s Lady Gaga–centered fourth iteration, but the eternal return of that film, for which Wellman also provided story architecture and other screenplay essentials, serves to reinforce the particular deathlessness of an auteur who has been an appealing subject for reevaluation. New York’s Film Forum dedicated an exhaustive 2012 series to his films. In 2015, Random House published the biography Wild Bill Wellman: Hollywood Rebel (written by his son). And Turner Classic Movies routinely shows Wellman films and documentaries about the man’s career.

In 1933, Wellman notched an absurd six director credits, a frenetic pace that hints at why some of the output is justly neglected. But standouts like the child hobo drama, Wild Boys of the Road, no matter how hastily manufactured, speak to the studio system’s knack for generating magic with efficiency when a skilled craftsman with sensitive, empathetic inclinations is at the helm. Between the release of Wings in 1927 and the enforcement of the Motion Picture Production Code in mid-1934, Wellman directed nearly 30 films, a streak scattered with socially conscious, oft-risqué marvels like a silent film on the hobo world, Beggars of Life (1928), and vehicles for Wellman favorite Barbara Stanwyck Night Nurse (1931), So Big (1932), and The Purchase Price (1932). These movies don’t shy from indicting capitalism for their characters’ (and audiences’) economic miseries, and the resort to vice and prostitution in films like Safe in Hell (1931), Frisco Jenny (1932), and Midnight Mary (1933) is treated sympathetically and with witty realism without candy-coating the soul-killing effects. Wellman introduced audiences to James Cagney in the railworker love triangle drama Other Men’s Women (a 1931 precursor to La Bête Humaine), and then directed the star-making The Public Enemy the same year. The grapefruit-smashing nastiness of the latter is equaled in intensity by the leftist anger of Heroes for Sale (1933), which ferociously excoriates the disgraceful livelihoods that greeted certain World War I veterans stateside.

That the director was able to make all of these tough, righteous films within the system bolsters biographer William Wellman, Jr.’s framing of his father as a lone wolf, though you could also view him as a dutiful employee simply fulfilling his bosses’ sensationalism quotas (lingerie, violence, populism), especially at Warner Brothers. On Wild Boys, Wellman’s mavericking ran into Jack Warner, with whom the buck stopped, and who insisted on a dud alternate climax of uplift and optimism (with promotion of the National Recovery Act) entirely out of tune with the bulk of the otherwise unrosy 67-minute film. In Wellman’s original shot-and-in-the-can ending (Earl Baldwin wrote the screenplay based on Daniel Ahern’s story, “Desperate Youth”), the juvenile protagonists are handed down substantial sentences by the same judge who in the alternate ending predicts bright futures; the boys are last seen being driven to detention centers. The Wellman ending highlights the film’s bleakness relative to Beggars of Life, in which the ragged tramp-heroes (Richard Arlen and Louise Brooks) escape together to Canada.

Beggars of Life

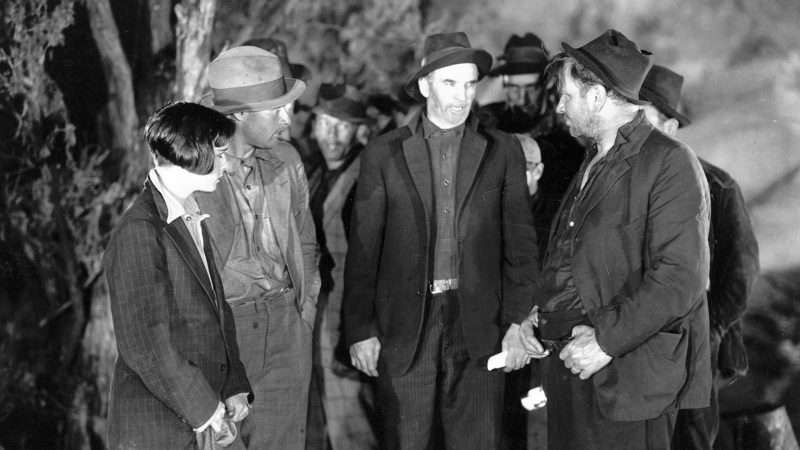

Wild Boys does not begin bleakly—opening scenes of scrappy teens Tommy (Edwin Phillips) and Eddie (Frankie Darro) employing cross-dressing and gas-siphoning to get in and away from a school dance in Eddie’s jalopy (named Leapin’ Lena, its exterior is covered in curious verbiage like “4% Bear Hunting—Mostly Teddies”) have a mischievous, Dobie Gillis-like lightness. That swiftly darkens when Tommy reveals that his family is “up against it”—when Eddie asks his own father for help, the latter informs him he is out of work now too. Tommy sells his beloved Lena for scraps, white-lying to his father that he was sick of it anyway. Feeling like financial burdens, they leave for the rails, hoping to somehow earn some money to eventually bring home. On a train, they mistake the dirty, freckle-faced Sally (Dorothy Coonan) for a male sandwich thief. They realize she is neither, and the three become a team bound for Chicago and Sally’s aunt, whom Sally assures them will welcome their surprise visit happily. Oddly, she does, though it is immediately apparent she’s running a brothel, which is promptly raided as the teens are in the kitchen innocently scarfing chocolate cake. Back hopping trains, the trio and their fellow young vagrants (in addition to character actors like Sterling Holloway, the bunch includes real-life vagabonds—an example of Wellman putting New Deal ethics into action) skip from “Sewer Pipe City” to the New York Municipal Dump, in the meantime retaliating against a brakeman (an uncredited Ward Bond) who rapes one of their number. At one point, Tommy, dazed from bumping his head on a switch, falls on the tracks and loses a leg; it becomes Eddie’s mission to raise his pal’s spirits and find him a replacement leg.

Like Beggars, Wild Boys was personal for Wellman, who dabbled in juvenile delinquency as a youth, “borrowing” cars and being expelled from his Massachusetts high school for stink-bombing the principal. His mother, a probation officer who once addressed Congress on the topic of delinquency, said her rapscallion son was the only kid she couldn’t handle. It was personal, too, because just prior to shooting he’d secretly married the young Coonan, a marriage that would produce seven children and last until his death. Though she lacks the presence and mystery of her Beggars counterpart Brooks (who doesn’t?), Coonan’s blinking eyes and wholesome appearance, which mask a weathered, at times abrasive independence, are affecting. The tomboy female hobo on film predates even Beggars, figuring in 1926’s lost Miss Nobody, and would persist with Linda Manz’s eventual runaway in Days of Heaven (1978) and in titles like Disney’s The Journey of Natty Gann (1985) and with the real androgynous waifs of Streetwise (1984). Wellman’s own draw to these hobos is unclear, though the added danger and persecution they face in addition to surviving makes them doubly compelling.

Wellman’s stylistic signatures mark Wild Boys—closeups of disembodied legs trudging from one disappointment to the next echo Beggars, and a camera snaking through the early party recalls similar moves in the drunken Paris R&R scene in Wings. As in Other Men’s Women, tracking shots occur mostly on railroad tracks—a cheap and easy shortcut for the frugal Wellman, who, despite his stubborn nonconformism, got work because he brought pictures in on time and under budget. Diagonal wipes keep a montage of newspaper headlines about the rise in tramping across the States brisk and informative—not a radical move in ’30s Hollywood storytelling, but the élan with which Wellman plies the whole toolbox make his specific no-fuss, dollar-bin filmmaking exciting and not anonymous. If films can have a glint in their eye, his best do.

Relegated to the second tier by the categorizers and scorekeepers of early American auteurism, Wellman is often lumped with the likes of Michael Curtiz or Victor Fleming, often viewed as journeymen with a handful of aberrant popular gold-strikings—in Wellman’s case, inaugural Best Picture winner Wings, A Star Is Born, Nothing Sacred, Beau Geste and maybe The Ox-Bow Incident. No amount of record-correcting could elevate Wellman’s status to that of artists like Hawks or Ray, but the newfound attention paid his pre-Code pictures, especially, has revealed a body of work with thrilling reserves of richness. TCM will continue to do its part when they re-air Wild Boys of the Road, one of the best of those pre-Code films—despairing, and vigorously alive.

Wild Boys of the Road airs on September 14 on Turner Class Movies.

Justin Stewart is a writer whose work has appeared in Brooklyn Magazine, Reverse Shot and elsewhere.