Interview: Andrzej Zulawski

The experience of watching a Zulawski film is exponentially rewarding when you’ve had the pleasure of seeing more than one. As with all dense cinema—and much of Zulawski’s work is packed with wordy dialogue, quick pacing, and confounding behavior—it’s a pleasant relief to identify recurring themes and details across multiple films. Attending a Zulawski retrospective is undoubtedly akin to going on a wild Easter egg hunt in search of doppelgangers, dandies, nude dancing and bodily convulsions, sweeping tracking shots following briskly walking women, spitting (both erotic and irreverent), nose picking, and food fighting. The title of BAM’s series comes as no surprise, although one hopes that audiences will be able to see beyond the prominent shocks to reach a more balanced view of Zulawski’s cinema, which also contains highly effective moments of sensitivity and pause.

Zulawski is a very philosophical director, in spite of his stated aversion to what he calls “big words.” He is fascinated by the concept of persistence of vision and he is drawn to an array of visual mediums, both technological and physical. Asking Zulawski questions about his work proves daunting, as he is himself an incessant questioner, and very defensive of his art and the details of his process. “Why am I [or why are you] doing ____?” is one of his favorite questions, so it is only fitting that his viewers should ask themselves the same thing. Why are we watching these crazy movies? Because they contain an inscrutable vitality that provokes questioning. Attentive viewers can shape their own viewing experience, seeking out individual points of interest while revelling in the expertly crafted images on the screen. Hopefully, Zulawski will find a producer sometime soon so that this cycle can continue.

Zulawski’s bicoastal retrospective (BAMcinématek’s “Hysterical Excess: Discovering Andrzej Zulawski” is joined by Cinefamily’s “The Unbelievable Genius of Andrzej Zulawski“) follows an incredibly successful run of Possession at New York’s Film Forum last December. Marshaled with the assistance of the Polish Cultural Institute New York and the Polish National Film Archive, the series provides a rare, not-to-be-missed opportunity to see some truly mind-bending films in 35mm prints. FILM COMMENT reached the inimitable filmmaker in Warsaw for a lively, wide-ranging, and candid conversation.

Possession

What have you been up to for the past ten years, since you shot La Fidélité in 2001?

I don’t know! So many things have been of interest to me that I can’t answer you frankly. It was ten years after I finished film school before I made my first feature film. And bizarrely, there is a correspondence. There is a parallel between ten years then and now. Ten years doing what? Trying to grow into something which resembles a man, a destiny. I don’t want to use these big words . . . I don’t know!

I hear that you’ve become a prolific author.

The last book I wrote was my 25th or 26th, and extremely Polish. I don’t know why, I’m just a Pole! It’s prose, mainly a novel but also essays. As I’m getting older, I’m afraid my books are becoming more personal. Most of them came from things that were undone, things I couldn’t do when I was very active making films. I don’t know, it’s a gracious curse to slip into some kind of—I won’t say “old” but certainly “older” age. Which means rethinking, rehashing, re-projecting one’s own life into perspective.

All of your films are inherently literary. You’ve taken works by Dostoevsky and Shakespeare, Madame de La Fayette and W.H. Auden among others, and you’ve found a way to weave these texts into your films.

My life is woven with literature, paintings, music. It’s inbred from my family, from the whole story of my life. If I suddenly had to make a film about a Ukrainian or an American worker in a factory, I’d be at a loss because I couldn’t try to understand how to be that. What I profoundly know is this world of culture—I hate this word, okay?—which is still my world, and therefore I worked against it almost as much as I was for it in my films.

And what of photography? That’s something else that appears to be a part of your world and also surfaces in your films.

Yes, sure. But film is photography.

Well, it’s more like the older brother of film, I think…

No, please understand that up until now—this revolution in electronics—film was frozen frames, 24 frames per second with the black spaces between them which made for 48. Film is in fact frozen photography that is animated by the fact that our eye doesn’t see it very coherently. We replace the black spaces with our memory of vision. Which by the way is a nice idea to explain cinema. So how could you explain film without photography? It would be radio. I was working as a photographer during my early days when I was a young student in Paris. My parents never had the money to pay for my film school so I was taking photos in order to afford it. And the problem of photography is that it’s grammar, it’s basic.

La Fidélité

When it comes to the characters in your films, the filmmakers are always artists, but the photographers are conflicted characters who are artists but are also struggling to make a living. They shoot photographs in order to survive, which is something that you did as well.

Yes, yes, you’re so right. On the other hand, you see I always wanted dearly to include the theater, to include photography, to include TV in the films I was making because it’s the same message. The medium is very slightly different, but in fact it belongs to the same area of expression, and this expression is visual. This expression is not telling you things with words but making you see it. I’m sorry, I hope I’m not getting too philosophical. I’m trying to be simple about it because the use of technology, the use of cinema, of the color stock, of cinemascope or whatever, today with the Red camera—it’s only so simple in a way, but the mystery, the question, “Why the hell do we do that?” stays the same.

Speaking of philosophy, I have to ask you about acting. You once said that training an actor is like planning a birth.

[Laughs] Did I?

Yes. I took it to mean that you can train someone or prepare them and give them a certain amount of direction, but then what ultimately comes out is just uncontrollable, natural and expressive.

No. It should be controllable, because otherwise the river that you are trying to direct will start to overflow. I guess in my work I am asking the actor to go deep down and understand why the hell he is an actor. Does he want to parade? Does he want to exist in a very superficial world or is he really, truthfully being an actor—which is almost a religious feeling. Please understand I am not a religious person in any sense of religion, okay? But I went to Siberia, I went to Africa, I went to the Caribbean, and I saw the voodoo and I saw the shamans and they are the best actors ever. Which means that if it is related to something so profound in our being, then why the hell are we playing with it? Why are our kids playing, and not just waiting for their piece of meat or whatever? This is basic. This is very interesting. This is fantastic. And if you are keen to go into it, if you are interested by it, I think it just helps today’s actors to forget that they are in the present and to remember that they are actors.

So actors are vessels?

No. They are complete, incomprehensible human beings.

You seem fascinated by the philosophy of acting. Even in On the Silver Globe [88] which is ostensibly a science-fiction film, you include speeches on the topic of acting and you have a character known only as “the actor.”

Right.

So you even address acting as a topic in this unlikely film.

Look, I don’t want to be banal. The easiest response when people are nagging me about this is to answer with Shakespeare’s words about the world being a stage, etc. But there is something really profound about it, in that the stage is so much better than other places. Yes, the world is a stage. The problem is, why? Why is it a stage? Why do we play these games? Why do we think that by playing these games we can say something true? Not banal, and not vulgar, just true. And to do it without making a sermon. Which is to keep it alive and keep it for show. We are making shows.

On the Silver Globe

I’m curious to hear what you think of this retrospective of your films that’s going to be here in New York at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. The title of the retrospective, it’s very catchy, but it’s called “Hysterical Excess”—

Do you want me to tell you the truth?

Yes.

This is the exact reason I am here in Warsaw and not in New York. I hated it so profoundly, it sounded so base—and I thank you for asking. On the other hand, I understand that these nice good people want to have something catchy. But I’m totally, totally aghast. I’m against this, and this is the reason I never came.

Thank you for your honesty.

[Laughs] My only vice is honesty.

I wanted to ask about it, because one can trace the thinking behind the title. You can see how someone might look at your films and come up with that title, but if you pick it apart, “hysteria” is a word that is commonly associated with Freud and his misinterpretation—

—with women—

Exactly. And “excess” is a word that might be reductive as a summary of your work.

Thank you. I’m glad you think so. Look, I’m so easily bored with cinema. It’s not because I don’t appreciate the effort, the acting, the script writing, or whatever. But most of it is so predictable, after five minutes I know exactly the pattern, the flow, how it will turn out. That’s perfectly all right, why not? But what these people call hysteria is, I guess, a will to provoke a certain kind of awareness, nervousness, open-eyed-ness, I don’t know what to call it. And actors who will reflect a hope on the audience. They won’t be bored. But this clinical term “hysteria” is very hurtful to me.

We may as well speak then about some of these nude scenes that stand out for American audiences in particular. They aren’t cheap or pornographic. I think that you present a very effective distinction in L’important c’est d’aimer [75] , when you have Fabio Testi’s character shooting porn for gangsters. Those scenes are absolutely devastating and distinct from the sex scenes in your own films.

Yes, well, that is basically true of so-called pornography. For instance, the scenes you just mentioned from L’important c’est d’aimer show the debasement, the turpitude. When I came to France after being thrown out of Poland by a Communist regime that hated my films, I found these purveyors of pornography, poor people trying to get any money out of doing anything. So I included it in the film. It’s pity, it’s empathy, and I hate it. But somehow they had to do it in order to exist in this society which I only vaguely understood. So I filmed it, like you said.

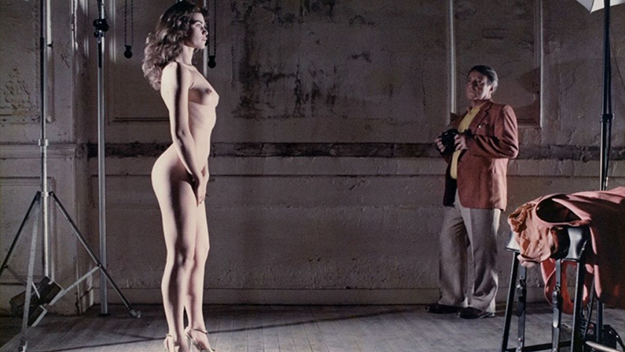

La Femme publique

I’d like to speak specifically about the nude dance scenes in La Femme publique (The Public Woman, 84) with Valérie Kaprisky. These are immediately memorable scenes that have a great effect on audiences. There’s an almost palpable sense of discomfort but also an awe at witnessing something—maybe it’s this act of birthing that you’ve described. I don’t know what we’re witnessing, but I think it’s art! And I think it’s essential that she be completely nude, that those scenes would have been something else entirely if Kaprisky had worn even a scrap of clothing.

Again, you are so totally right. It’s contrary to these pornographic ideas, the horrible scenes shot in That Most Important Thing that I included just to make it understandable that our guy the hero is really making his earning, his living in the gutter, okay? Here you have on the contrary in La Femme publique, you have this extraordinarily beautiful, resplendent body and free the way god made her. It’s major, and not to film it would be really a disgrace! So it never occurred to me to put a scrap of something on her you know, as if the Vatican would cover scraps on Michelangelo sculptures, or censor the paintings in the Sistine Chapel. I think that the human body is art when it’s loved and treated with awe, and it shouldn’t be covered. It is what it is and please be happy for it. This girl has it. The woman who wrote the novel that was the basis of the script described some sort of semi-pornographic scenes in the Pigalle district that were so crappy so I thought it better just to put it in front of the camera, just to say: look, this is marvelous, this is a miracle. How can you be as beautiful as that? How can you be as human and at the same time animalistic and how do you say…

Uninhibited?

Yes, yes. For me it was when we understood that she could do that, I said to my assistant, look, this is the film! Forget the rest, this is it!

I like how in one of the scenes she discovers the photographs, and she appears to be disgusted or upset that they are just of her body from the neck down.

Because he never shot her face. He was doing pornography, she wasn’t. She was dancing, in a beautiful sense of the word. You know St. John? He said “those who don’t dance”—I’m sorry, I’m translating from Polish but—“those who don’t dance will never understand how it is.” And this is something so extraordinarily poetic and simple. So she’s dancing and this guy was only interested in her tits and bottom and, well, yeah.

In La Fidélité [00] Sophie Marceau’s character takes photos of a nude hockey player and her editor says: “With a head it’d be a sensation; headless it’s porn.”

[Laughs] Very well seen, thank you.

Your comments on dance make me think of the title character in The Devil [72], who says that he always wanted to be a dancer.

Yes. He dances the world by the end of the film.

The Devil and On the Silver Globe are two of your films that you made in Poland that take place hundreds of years either in the past or in the future but apparently struck a chord with contemporary politics.

And I am so glad for that, really. I don’t want to bother you with Eastern European politics, but when we were making The Devil, the parallel was that the secret police (which was the Communist police) took advantage of the Polish youth and the idealistic thinking of the young people just to make demonstrations and to throw out a certain group of guys who were installed in power for the benefit of another group of guys who wanted this power. And those groups were so dirty, so ugly, so totally hateful to me that this is what we tried to render. But as we couldn’t do it directly, I put it into the style of 18th-century costume and masks hoping that this contemporary nerve of political manipulation will be apparent by the end.

One of the lines in The Devil is “deprivation is when you live by the ideals of other people.”

I made this film in ’72, I guess. What can I add today? Please tell me.

L’Amour braque

Years later in France you made La Femme publique and L’Amour braque [85] which both touch on the youth movement and its flirtation with terrorism. This flirtation is a type of idealism that many European intellectuals adopted in the late Sixties and Seventies but perhaps had more of a vital relevance when you’re from the Eastern Bloc.

Oh, Margaret, this is very complicated. As you said, there was quite an interesting development where I was coming from. When I met Fassbinder, it was this whole group of mostly German leftist intellectual filmmakers who were talented and serving a cause which I still believe was disastrous… This whole terrorist movement that they were so keen to pay for was a shocking thing for me. At the same time, coming from Eastern and not Western Europe I knew not to pronounce too harsh a judgment on their will to dispose of capitalism, their love of Fidel Castro, etc. etc. It was quite a moment in the history of the intellectual movement and it moved through philosophy, ethics, literature, and cinema. It was a wave. And I was so strongly opposed to it that my only way to say that I didn’t agree was to show what was shown in L’Amour braque.

Francis Huster and Tchéky Karyo give strong performances in it. Women usually carry the starring roles in your films, but the men are impressive as well. In Possession [81], for example, Sam Neill really holds his own alongside Isabelle Adjani.

I would say that Sam Neill, Francis Huster, and the others had the difficult parts to play because the women in these films appear like a tornado. They were banging into a scene and making a great fuss and being so expressive, and like you said at the beginning, “hysterical,” right? They make all of this noise, but the male actors are just playing the glue between the scenes. They keep the films together, which may not seem like such a fantastic starring role, but they did it with such talent and devotion that I almost like them better than the women. The women got the prizes, they got the applause, they were brilliant, they were spastic. But the men had the hard work of keeping the whole film together.

I’ve also noticed the recurrence of male characters that could perhaps be considered “dandies”…

I hope not! And why do you say dandy? I don’t quite understand. I saw my actors working deeply in the mine shaft, you know? Digging the coal. And providing the material upon which the women bounce against, and they were brilliant bouncers, so I’ve often felt that one day I should really make a film about a man! But I never did. It’s always been about women, who are so much more interesting.

You should make a film about a man.

I need a producer! Please! Tomorrow!

It’s true that your leading males have to take the brunt of the females, and they often end up cuckolded.

Most of them are. I’m sorry, because “dandy” is not a word that I like. Today for instance in Poland, all the political leftist intellectuals—they are dandies!

I was thinking of Klaus Kinski’s character in That Most Important Thing, characters on the sidelines who are usually associated with the theater and exhibit a certain effeminate, libertine style.

Yes, you are touching something which is essentially right.

The Devil

And even the title character in The Devil, prancing around…

That’s extremely perceptive of you. Because both of those actors had sexually mixed personalities. They were as much womanish as they were mannish. They were somewhere in between, I don’t know. And these fluctuations in expression of feelings on the screen, for me it’s brilliant. In both cases brilliant. Maybe it’s coming from their, how do you say it, bisexuality? I don’t know. I don’t want to go into that.

I know that I chose Kinski first for his extraordinary physique and also because he was the first Hamlet being shown in the ruins of Berlin in 1945. He was an extremely gifted theatrical actor, and he was a madman. He was on the verge of stupidity sometimes and he did these spaghetti Westerns and he went to Italy, God knows why, to earn some money. And when we took him for this film he was nothing. Nobody wanted him any more. He was washed up. He was finished. And it was after L’important c’est d’aimer that Werner Herzog took him for some very interesting films. Klaus was a case, a border case of insanity which suits me fine.

[Francis] Huster, he had gone so far into this strange twilight zone between appearances. He was trying to be—you remember the French actor Gérard Philipe? He was the biggest star in French cinema after the war. Fanfan la Tulipe, The Re Black, he made so many films. And he had this extraordinary romantic tempo and appearance. And I think that Francis Huster was always trying to be him. So both of them had big complexes, am I clear?

Very clear. Also Jacques Dutronc. He’s a very talented, vulnerable actor.

Yes. But Jacques never was an actor. Jacques was a singer who was extremely popular and successful in France when I took him for L’important c’est d’aimer. He’s a very strong, highly intelligent, very—I don’t know why exactly—desperate man. And he showed it in L’important c’est d’aimer with humor. And he showed it in My Nights Are More Beautiful Than Your Days, which is another film I did in which he was very ill. His character was dying and his emaciated face, his shrunken body was so moving to me that when confronted with the vitality of Sophie Marceau’s character, it tore my heart out.

Back to the dandy supporting characters for just a moment: how about Heinrich in Possession?

Oh yes, he is, but he is a phony one. My dandies are the right ones and he is a phony! He’s a pseudo Buddhist, a pseudo sexual being, a pseudo everything, and in fact if you look at the film attentively you’ll see that you never know what kind of trade he’s in. He’s not a writer, he’s not a painter, you won’t know by the end of the film.

Well, he lives with his mother. Maybe he has no trade at all.

Oh, the mother was a sweet, sweet character. Totally mad. I loved her.

I think we can agree that you’ve elicited outstanding performances from your male actors as well as the females.

No, I only helped. They had it in them. Believe me, you can’t push out a stone. They have it, and you have to help.

A few of your French films have background references to Gone with the Wind. Why is that?

Yes. You know very well that my films are mostly about women and the best performance of a woman on screen is Vivien Leigh in Gone with the Wind. If you look at it really carefully, it’s fantastic. I know that she had a lot of problems playing that part. She went at night to see George Cukor in his villa because she was being directed by a very manly director (out of the three) and she needed some refuge with Cukor, who was a homosexual. A great director and an intelligent man. By the end of the story she’s fantastically brilliant. And this is the only thing I remember from the film, her triumphant womanhood.

It’s a film that appeals to both actors and cinephiles.

[The characters] want to achieve that level of how do you call it, actorhood? I don’t know. But Vivien Leigh’s case is tragic. She finished a totally insane person almost in a hospital and she paid very dearly for her talent. And to bring this back to what you were asking at the start about actors: you do it well, you do it right, you pay a heavy price.

Possession

Possession has been singled out lately on the repertory circuit in the U.S. after a very successful run at Film Forum. You’ve called it a “personal” film. What do you think of its recent success?

Please, how can I answer that? Possession was born of a totally private experience. After making That Most Important Thing in France, I went back to Poland to get my family (which at the time was my wife and my kid) and bring them to France. I had two or three interesting proposals to make really big European films. But when I returned to Poland I saw exactly what the guy in Possession sees when he opens the door to his flat, which is an abandoned child in an empty flat and a woman who is doing something somewhere else. It’s so basically private. Now I can go back to it many years later, but even the dialogue in certain kitchen scenes and certain private scenes is like I just wrote it down after some harrowing day. So it’s amazing how such a private thing became a kind of icon. You know Adjani got the prize at Cannes for this film, she got the Cesar which is the French Oscar and 14 other prizes in many festivals. Please believe me, it’s mentally very disturbing to see that your very private little film became something in which so many people recognize something of themselves. Thirty years later I’m still thinking about it.

There’s obviously a personal truth to it but it’s also one of your most fantastic films. It jumps effortlessly between different genres of filmmaking, with a surprising turn toward horrific science fiction. It’s an interesting way to tell such a personal story.

It stems again from the simple fact that I was living in Paris and I went to see Ingmar Bergman’s Scenes from a Marriage. It’s an extremely well acted and brilliant film, but I left the cinema feeling empty. I went out and I said, All right, the analysis is perfect. It’s cold, it’s brilliant, like always. But so what? I was walking the streets I remember, it was raining and I said look, the beauty of the stories that we are telling our children is the moral at the end. That is to say that there is always something fantastic by the end of the story. So they walk along the pavement and they go into the house… this is the first floor, this is the kitchen, blah blah, but what’s in the attic? And I was thinking, okay, in my little story what attic does it really have? If I go up the stairs out of the realistic realm and into the fantasy, the science fiction, what is the fairy tale? What is the bad fairy tale at the end? So I went to the attic and I found a monster.

There’s comedy in the film as well.

One of the things I’ve always regretted, especially when I was making films in Europe: don’t assume that the French have a keen sense of humor. They have the French sense of humor which is quite peculiar, but I always tried in all of my films to include things that make me laugh. Sometimes in the most dramatic scenes, sometimes just to accompany these scenes. In Possession for example there’s a procession of shots that really make me smile. There’s the detective who slips in some dog shit on the pavement while he is following the girl. It’s not exactly slapstick but close.

Thank you. I’m looking forward to seeing your films in the theater.

The only way! Please, the only way!