TCM Diary: Paul Newman Directs

On the Harmfulness of Tobacco

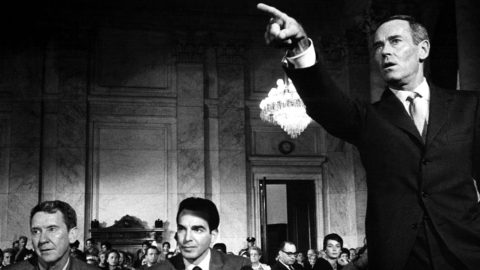

In 1959, Paul Newman saw Michael Strong perform Chekhov’s one-act play On the Harmfulness of Tobacco at the Actors Studio in New York. Overwhelmed by Strong’s performance, Newman resolved to preserve it on film. He shot a short movie of Strong’s Chekhov monologue, using his own money, and the result was briefly shown in two theaters in 1962.

Newman’s On the Harmfulness of Tobacco is carefully and sensitively shot in black-and-white using high-contrast lighting for close-ups of Strong, who is very naturalistic and very centered in his delivery. Strong does the kind of acting that was favored at the Actors Studio in this period: enclosed, private, mysterious. Newman shoots Strong’s work lovingly and attentively, sometimes from low angles as if he were at Strong’s feet and wanted to learn. Self-conscious about his extraordinary physical beauty, Newman longed for people to look past his Greek god surface as an actor, and this need to delve deeper is what animates his small body of work as a director as well.

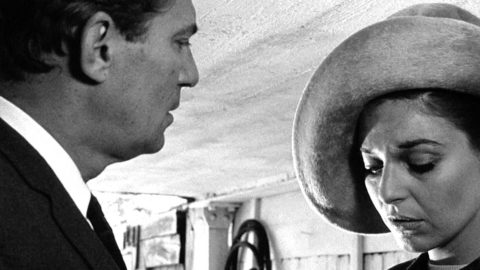

In the six films that Newman directed after his little-known Chekhov short, he practiced the most subjective and intimate kind of cinema. He wanted to put you inside the heads of his characters and make you feel exactly what they were feeling. In his first directorial feature Rachel, Rachel (1968), Newman uses both the narration of private thoughts and visualized fantasies to make us experience what it’s like to be Rachel Cameron (Joanne Woodward), a schoolteacher who lives with her demanding mother in a small town and is still a virgin at 35. The past and the present mingle together for Rachel, as if her life has never really gotten started. She is prim and arch and decent and polite, but her eyes get a hard look in them sometimes that signals her morbidity, her self-criticism, and her very repressed anger.

The Effect of Gamma Rays on Man-in-the-Moon Marigolds

Woodward and Newman married in 1958 and stayed married for 50 years until his death in 2008. Woodward appears in five of his six credited films as director, and three of them serve as vehicles for her to show off her mature talent. Newman was making an impact as an actor playing glamorous losers like “Fast Eddie” Felson in The Hustler (1961) and martyrs like Cool Hand Luke (1967), but with his wife, he created films about very un-glamorous female losers like Rachel Cameron and the scabrous Beatrice in The Effect of Gamma Rays on Man-in-the-Moon Marigolds (1972).

There is something feminine about Newman’s screen losers and something masculine about Woodward’s anti-heroines in Rachel, Rachel and Gamma Rays, both of whom have been left behind by life. But the conscientious Rachel earns our sympathy while the blunt, grueling Beatrice, whose habitual physical stance is that of a defensive Mafia hit man, can only garner revulsion and pity. Newman worked very closely with Woodward to create both Rachel and Beatrice. “We have the same acting vocabulary,” Newman said after filming Rachel, Rachel. “I would tell her, while she was reading a line, ‘pinch it’ or ‘thicken it,’ and she knew just what I meant.”

Rachel, Rachel stays very close to its source novel, Margaret Laurence’s A Jest of God (1966), skipping only some of Rachel’s more explicit sexual fantasies. Newman and Woodward are both willing to delve into unattractive and private emotions in the films they made together, but they are both creatively reticent when it comes to sexuality. Usually in a film like Rachel, Rachel we wait to see what flashy trauma from the past might make the main character worthy of our attention. But Rachel Cameron is ordinary even in what she suffers. And that choice feels more risky now than ever, even with Jerome Moross’s memorably plaintive score bolstering Woodward’s performance during some of Rachel’s solitary walks.

Rachel, Rachel

There is a sense in Rachel, Rachel but particularly in Gamma Rays that Newman and Woodward are exploring the lives of Rachel and Beatrice without compromise and without any softening or leavening. The result is two films in which they both risk alienating their audience in order to hew as closely as possible to what they saw jointly as the hard truth about small, failed, and embattled lives. Woodward’s very flinty, steamroller-like performance in Gamma Rays is not the sort of work likely to win much love, approval or admiration. But it does represent what so many players were striving for at the Actors Studio: unvarnished and often ugly personal truth.

Newman cast their daughter Nell as the young Rachel in Rachel, Rachel and as Beatrice’s younger daughter in Gamma Rays, where she doesn’t seem like a child actress but like an actual and very shy child staring with her piercing blue eyes at Woodward’s yowling, freakish character. In moments of high stress in these two films, Newman puts his camera right in Woodward’s face, so close sometimes when she cries in Rachel, Rachel that she goes out of focus. Newman’s urge as a director always seems to be to dissolve the barriers between himself and the person he is looking at and also between the character and the woman who is his wife. These characters are carefully created and imagined, but Lee Strasberg always taught at the Actors Studio that actors needed to find themselves in the roles that they played.

Newman’s honed his own work as an actor and steadily improved as he got older, so that by the time of Fort Apache, The Bronx (1981) and The Verdict (1982) he had burned through his earlier self-consciousness and found a deeper, more focused truth, the same deep truth that he so admired in Michael Strong’s performance in Chekhov’s one-act. Motivated by the spirit of preservation that had made him film Strong’s tour-de-force, Newman directed a careful film of Tennessee Williams’s The Glass Menagerie (1987) in order to capture Woodward’s performance as Amanda Wingfield.

The Glass Menagerie

Like his earlier movies with Woodward, Newman’s film of The Glass Menagerie seems to take place in a private space where actors can explore tough emotions without worrying about results. Newman’s career as both actor and director is a body of work that most faithfully exemplifies the tenets of the Actors Studio in its 1950s and ’60s heyday. The beautiful but uneasy student at the feet of Michael Strong in 1959 had by the 1980s become masterly himself.

Rachel, Rachel and The Effects of Gamma Rays on Man-in-the-Moon Marigolds screen March 26 on Turner Classic Movies.

Dan Callahan is the author of Barbara Stanwyck: The Miracle Woman (2012) and Vanessa: The Life of Vanessa Redgrave (2014).