In Memoriam: Peter Hutton

Images of Asian Music (A Diary from Life 1973-1974)

In 1962, when he was 18, the American filmmaker Peter Hutton enlisted in the merchant marines. He spent the next 15 years—during which he’d later say he was “hit with a heavy case of wanderlust”—intermittently coming home and shipping back out, and the 20 silent, nonnarrative movies he made between 1970 and 2013 all seem to come from a state of transience, of exploratory travel, of dropping in and passing through. Some are explicitly travelogues. Images of Asian Music (A Diary from Life 1973-1974) consists of footage Hutton took on his Bolex during a stop in Thailand and Indonesia. Budapest Portrait (Memories of a City) (1984-6) and Łódź Symphony are his radiant, gloomy portraits of two Eastern European cities; Skagafjörður (2004) his breathtaking color view of North Iceland.

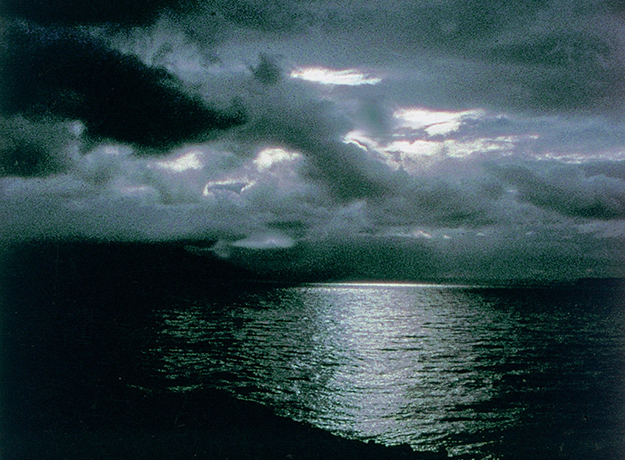

Others are the visions of the Catskills and the Hudson River Valley—Landscape (for Manon) (1987), In Titan’s Goblet (1991), Study of a River (1996-7), and Time and Tide (2000)—for which Hutton is best known, and which, taken together, maybe offer the best introduction to his sensibility as a filmmaker. Even when he was filming an American city in or near which he’d lived, as in his early movies set in the Bay Area, his two films shot in Massachusetts or his four about New York, Hutton handled his camera like a curious outsider, lingering on the flow of water or the movement of clouds, taking in people in brief, penetrating but oddly distant portraits, not staying in any one place too long. (Of the above-mentioned films, only Time and Tide, Skagafjörður, and In Marin County—Hutton’s brief and relatively minor first movie—were shot in color rather than soft-textured, slightly underexposed black-and-white.)

One might expect Hutton’s films to have a kind of restless and roving energy, or to fret over the same sorts of doubts about wanderlust that Elizabeth Bishop—one of Hutton’s fellow inveterate travelers—put with wry self-aware humor. (“What childishness is it that while there’s a breath of life / in our bodies, we are determined to rush / to see the sun the other way around?”) They might be expected to overlap, in the tone of their attitude towards travel and adventure, with Claire Denis’s film The Intruder (2004), in which an aging man with a shady military history goes in search of a black-market heart transplant. He ends up in the South Pacific, approaching a mountainous shore over which a deep, violet night is falling—a vision of someone cast adrift at the end of the earth.

Landscape (for Manon)

Watching his films at a recent retrospective at Anthology Film Archives, I was struck by a sense that Hutton, who died this past June at 71, was largely immune to these kinds of doubts. His films almost never seem lonely or bereft or confusedly unmoored. Instead, they have a kind of deep settledness and self-assurance. They come off as the work of someone for whom independence—the freedom to see the sun every possible way around—was a calm and constant pleasure.

Hutton’s movies are all visions of specific places, and they suggest what a distinctive way he had of filming landscapes and cities. His impulse was to capture locations piecemeal, accumulating fragmentary impressions that—depending on the place in question—ranged from grand panoramas to details like the curls in a plume of smoke or the light a streetlamp sends through fog. In his interviews and public statements, Hutton tended to play up the casual, unsystematic aspects of his way of working. “I don’t have the feeling that you’re fighting the technology at all,” the filmmaker and critic Robert Gardner remarked in 1977 during Hutton’s televised appearance on his Boston-based interview show Screening Room. “This may be a conscious step on your part—to subdue the technology by minimizing it . . . making it as minimal a commitment as possible.” Hutton’s reply is a model of poised confidence and evasive understatement:

I immediately just tried to get into the habit of having my camera with me so I could be fairly spontaneous with it. Every filmmaker knows that it’s hard to be spontaneous with a movie, because you’re dealing with a lot of equipment, you’re dealing with a budget, you’re dealing with logistics. It’s just hard to pick it up and to do things. But this was something I thought was so much more exciting. It was a different approach to filmmaking. You shoot spontaneously and you accumulate footage and you go back over a period of time and say “this is what I’ve done.” And maybe you want to narrow that down to some more heightened impressions of what you’re seeing. But essentially what I’m doing with a camera is just accumulating images.

New York Portrait, Chapter II

Hutton never gave up this way of talking about his own movies. “I’ve never felt that my films are very important in terms of the History of Cinema,” he memorably told Scott Macdonald in 1995. “They offer a little detour from such grand concepts.” In 2011, he told the audience at a Hampshire College screening of At Sea (2007)—his hour-long account of the assemblage, travels and afterlife of a commercial shipping vessel—that “I often don’t even think of myself as a filmmaker in the classical sense of making films. Because they’re really just observations; they’re sort of notes on looking at things that interest me in the world. They’re very simple; nothing too complicated going on.”

Looking at Hutton’s films, you might be fooled into giving these coy remarks more trust than they deserve. By the time he made such movies as the beautifully titled New York Near Sleep for Saskia (1972) and the first of his three New York Portrait films (1978), Hutton had started punctuating his films with brief stretches of total darkness to isolate and outline the individual shots. Each image started to seem—as the critic Michael Sicinski wrote in an insightful recent essay on Hutton for Cinema Scope—like a “monad of meaning,” strung together in “an open, almost anti-associative mode.” It could seem as if Hutton was inviting each of his viewers to compile their own mental anthologies of his best shots, mixing and matching images from different films and shuffling them around. In this kind of mental catalogue, Saskia’s images of glowing curtains, luminous walls, and bits of dust suspended in beams of light could be interspersed with, say, the close-up of a statue’s four-fingered hand midway through Łódź Symphony, the eerily calm images of figures moving through a towering bamboo grove in Images of Asian Music, the billows of smoke that coalesce into beguiling abstract patters in Boston Fire (1979), the images of glittering water that likewise verge on abstraction in Study of a River, or the gliding shot of ice sheets fracturing and collapsing near the start of Time and Tide.

See enough of Hutton’s films and you do find yourself chopping them up shot-by-shot like this, as if Hutton’s genius was really for “just accumulating images” or compiling stray “notes” and observations on the places he saw. But if Hutton’s editing gives the sense of being “almost anti-associative,” in Sicinski’s words, it’s also motivated by an awareness that different places and forms of travel require different ways of arranging or associating images, different patterns of rhythm, and different emotional tones. Each of Hutton’s films has its own atmosphere and its own associative method. What we get, watching these movies together, is a kind of catalogue of what Hutton thought freedom looked like under varied conditions and at different stages of a person’s life.

*

Three Landscapes

Hutton was born in Detroit in 1944 to a father with a casual interest in the movies and a background in the merchant marines, which Hutton has said gave him one of his initial motives to enlist. Between ship-offs in the early-to-mid Sixties, Hutton studied painting at the University of Hawaii. At the time he made his first films, he was taking courses at the San Francisco Art Institute and hanging out with artists for whom total freedom was something like a guiding ideal. The title of his second film offers a summary of his daily activities in California, including his employment at the Bay Area film center that now distributes most of his work: July ’71 in San Francisco, Living at Beach Street, Working at Canyon Cinema, Swimming in the Valley of the Moon (1971). In that movie, he filmed his house, pets, and friends with fond detachment, punctuating lively footage of his fellow artists smoking, biking, and frolicking naked under a sprinkler with the kinds of environmental observations that would dominate his later films.

Hutton always had an uneasy relationship with autobiography. He came to filmmaking at a moment when a cluster of prominent men in American experimental cinema—Stan Brakhage, Ed Pincus, Jonas Mekas—had started compiling their movies out of diary-like pieces of personal footage taken on the fly. With July ’71 in San Francisco, Hutton did just that. But he arranged his shots so carefully and lingered over them with such serene interest that the film feels less like a diary than a study of a specific environment and the people who lived in and around it. In successive films, Hutton was still less forthcoming about his personal attachments. It was uncharacteristically indiscreet when, in Images of Asian Music, he included a clip of a nude woman laughing and sipping a drink on the edge of his bed. It’s also the only moment in any of his films when one wonders if he’s encroaching, in making this footage public, on another person’s privacy despite so protecting his own.

By the late ’70s, Hutton tended to avoid references to specific people except in his films’ dedications—the title of New York Near Sleep for Saskia identifies the daughter of the New York artists Red Grooms and Mimi Gross—or in specific shots on which a movie could close or turn, like the close-up of his young daughter’s face that concluded Landscape (for Manon). Instead, he focused on capturing the visual textures and moods of individual settings: the movements of firefighters against a burning roof in downtown Boston; the antics of a sidewalk clown in New York (in Saskia); vistas of Coney Island; fireworks over the skyline; flooded and snowbound city streets (in the New York Portrait trilogy). The effect is refreshingly humble, especially in contrast to the confessional visions of domestic breakdown both Brakhage (Tortured Dust) and Pincus (Diaries) released in the first half of the Eighties. Among the stars of the American avant-garde whose ranks he’d joined, Hutton seemed to stand out for his quiet self-possession—his disinclination to draw attention to himself as he pursued increasingly adventuresome programs of travel and ever more sophisticated ways of handling light, shadow, texture and visual depth.

Study of a River

When he took a faculty post at Bard College in 1984, Hutton got a base from which to travel and—in the Hudson River Valley—a subject for some of his finest films. It’s hard to find comparisons anywhere else in American movies for the unfurling cloudscapes at the center of In Titan’s Goblet, or for the shots in Study of a River that turn the Hudson’s surface into, alternately, a mirror, an ice sculpture, a conveyor belt, and a field speckled with hundreds of star-like glimmers of light.

Hutton’s Hudson portraits have often been compared to early “actuality” films and to the work of 19th-century painters like Thomas Cole and Fitz Henry Lane. The analogies help suggest what his movies from this period look like, and Hutton acknowledged them both. (He titled In Titan’s Goblet after a Cole painting and excerpted a 1903 river scene called Down the Hudson at the start of Time and Tide.) But they need qualifying. To insist on them too heavily would be to risk casting Hutton as an impassive maker of monuments to beautiful or striking landscapes. In fact, he’s a wily and dynamic intellect, someone who safeguarded his privacy carefully but who nonetheless invites us to see his movies as notebooks of his own idiosyncratic compiling. There’s a strong personality behind all of Hutton’s films, but its qualities can sometimes be mistaken for aloof impersonality: nonchalance, quietude, deep confidence in one’s own resources and powers.

Skagafjörður

Central among those resources were the particular film stocks Hutton used. Hutton’s movies might resemble early actuality films in the isolation of their shots, or in their plain, direct attention to human faces and natural phenomena. But they’re just as much a product of a time when American filmmakers were acutely conscious over how specific film materials could, or should, be manipulated to suit a given subject. In a tribute essay posted last June, the filmmaker Jon Jost wrote with helpful precision about Hutton’s black-and-white technique:

He shot in Kodak Tri-X reversal, deliberately underexposing one and a half to 2 stops, getting a grainy rich image of a wide range of grays-to-black and almost no whites. He knew how to exploit the play of light which drew him like a moth in combination with the granular texture of the emulsion.

When Hutton turned to color, in such films as Time and Tide, Skagafjörður, and Two Rivers (2003), he had to hit on new interactions between the film stock and natural light. By Skagafjörður, he was singling out wide shots of vistas that were somehow layered or striated—strips of cloud, water, or rock that varied in color and texture, stacked on top of one another like layers of soil or rings in a tree. North Iceland was the most remote place he’d ever filmed, and in Skagafjörður, for the first time in decades, he included a kind of self-portrait to mark his arrival at the farthest place to which he could travel. Late in the film, the rest of which is all footage of wide unbounded landscapes, Hutton cuts to a disarming interior shot of a seascape seen through the window of a darkened room. When he cuts back to another wide view of the ocean, it’s in an image with a solitary human figure crouched behind a camera at the far left-hand side of the frame.

*

Three Landscapes

Hutton’s last two films were color triptychs longer than, and quite different from, anything else he made. At Sea begins with the construction of a container ship in South Korea, follows the freighter—or one like it—as it moves through the North Atlantic on a voyage from Montreal to Germany, and ends on a vision of the same kind of vessel, now abandoned, being stripped for scrap metal on a beach in Bangladesh. The scenes in Three Landscapes (2013) have a less obvious forward progression. That film begins with views of steel mills on the industrial outskirts of Detroit—Hutton’s first cinematic treatment of his home city. From there it proceeds to farmland in the Hudson River Valley, where Hutton superimposes shots of agricultural laborers working the fields over images of clouds rolling through the Catskills. The last sequence is of camel herders harvesting a salt deposit in northern Ethiopia, a passage Hutton conceived as a kind of sequel to a film Robert Gardner shot in the same region in 1968. (The movie was shot on 16mm but shown, unlike any of Hutton’s previous films, on DCP.)

In 2015, both films were shown at New York’s Miguel Abreu Gallery as three-channel video installations, a format that suited Three Landscapes well and cost At Sea some of the power it has as a sequence. Oddly, it’s these more structurally defined movies—with their sharp three-part divisions—that best conform in their visual language to Hutton’s claim that his movies are “really just observations.” They tend to have less of the density, richness of texture, or complex trade-offs between stasis and movement that marked Hutton’s earlier films; here, Hutton had started making the casual, less formally ambitious images he claimed coyly that he’d been making all along.

There is another aspect of these films that sets them apart: never before had Hutton chosen such politically charged subjects as these visions of commodity production and manual labor. It’s hard to watch his last two movies without wondering what kind of a politics Hutton had developed by the end of his life. His insistence on maintaining his privacy and passing through the world with a kind of quiet, curious self-possession might seem like a way of avoiding the pressure to stake out a set of political commitments. But the last shot of At Sea, in which a small group of Bangladeshi men approach the camera quizzically and peer into the lens, is a reminder that Hutton took a more active part with the people he filmed than that of a bemused observer.

Łódź Symphony

That shot makes one remember how closely Hutton always looked in his films at people at work: the construction crews in Łódź Symphony; the cockfighters, canoe-makers and bamboo harvesters in Images of Asian Music; the firemen in Boston Fire. He filmed these people with unsentimental, comradely respect, and he had a kind of principled aversion to intruding on their lives and thoughts. Both he and they were on the clock; why waste time interrogating each other? There was work to be done. “A lot of the guys on the ships were loners,” Hutton recalled in 2009 about his first trip to Calcutta with the merchant marines. “One of my best friends was an ex-con that had just gotten out of Oahu State Prison, a Portuguese guy. I never asked him why he was doing time. He was cool, a nice guy. He just needed a gig.”

Max Nelson is an editorial assistant at The New York Review of Books and writes the Restoration Row column for Film Comment.