Kaiju Shakedown: Kamal Haasan

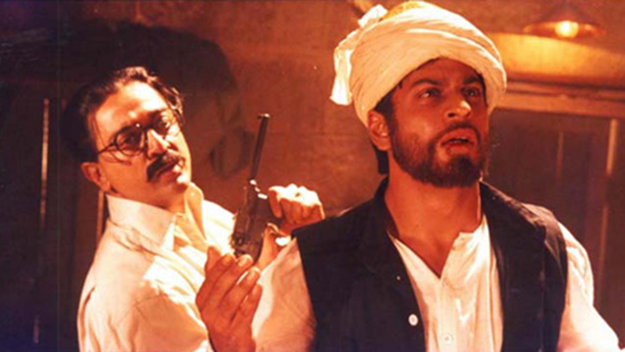

Aalavandhan

I fell in love with Kamal Haasan when I saw him beat himself up. This was shortly after Ronald McDonald helped him buy some heroin. I needed to know more, and so I dug into his filmography and I came to know Haasan as the Tamil actor who parlayed his massive fame into directing and starring in a musical about the man who tried to assassinate Gandhi, as the actor who starred in one film playing a dwarf, who played quadruplets in another, who played President George W. Bush in a third, and who starred in unofficial Indian remakes of Mrs. Doubtfire, What About Bob?, She-Devil, and Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down!.

Some actors have big filmographies. Kamal Haasan starred in his 100th film by 1981 when he was 27. To date he has 208 credits, and that estimate is probably on the low side. But it’s not so much the number of roles that makes him stand out, but their sheer contrariness. In his comedy Thenali (00) he plays a patient so annoying that his own therapist ties him to a tree with a bomb strapped to his body. In Indian (96) he plays a father bent on murdering corrupt officials, one of whom is his own son (also played by Haasan), who forged an inspection certificate for a school bus that subsequently crashed and killed all 40 children on board. By the end, Haasan has killed Haasan.

The movies he directs shouldn’t work. They’re full of stunt casting and deeply uncommercial. Yet after taking over from the director of his Mrs. Doubtfire remake, Chachi 420 (97), Haasan directed his dream project, Marudhanayagam (97) a biopic of Muhammed Yousaf Khan, the military leader who allied with the British East India Company to slaughter and subdue Indian freedom fighters. While the movie was expected to be one of India’s biggest productions, only 45 minutes were completed before it was shelved. After taking a two-year break, Haasan wrote, directed, produced, and starred in Hey Ram! (00).

Hey Ram!

It would be hard to think of a more perverse pet project than Hey Ram!. The 1947 Partition (when India split into Muslim Pakistan and Hindu India) resulted in riots that left hundreds of thousands dead, and it’s a taboo subject in Indian cinema. Hey Ram! revolves around the assassination of Gandhi, one of the country’s most sacred icons. The star of the show is Haasan, playing Saket Ram, a Hindu archaeologist whose work with his Muslim colleague (played by superstar Shah Rukh Khan) is disrupted when Partition is declared. Set in the two-year period between the Communal Riots of 1946 and the assassination of Gandhi in 1948, it chronicles Ram’s descent into violent Hindu nationalism, only to repent at the last minute and throw himself at Gandhi’s feet, begging for forgiveness—mere minutes before another Hindu nationalist shoots and kills the great leader.

A box-office flop, pulled from release in many parts of the country after only a few days, Hey Ram! nevertheless carved out a style for Haasan’s big projects: controversial subject matter, unlikeable main characters, and Haasan playing a role that involves some kind of stunt. His next major film, Aalavandhan (01; aka Abhay in Hindi), couldn’t have sounded worse. It’s the story of a psychopathic serial killer whose twin brother is an Army commando, with Haasan playing both roles, shaving his head and gaining 30 pounds to play the psycho. That may sound like a terrible combination of Hannibal Lecter serial killer tropes and good twin/bad twin silliness right out of Big Business. Instead, it’s very nearly an exploitation masterpiece.

Major Vijay (Kamal Haasan) is a gruff Indian Army commando who takes infinite pleasure in his work, which mostly involves crucifying terrorists and tucking bombs beneath their chins. A trifle sadistic for some, but in his commando squad it earns him “Employee of the Year.” He’s a workaholic but he’s found the time to get engaged to a television news anchor, Tejaswini (Raveena Tandon). When their nuptials loom, he grits his teeth and takes her to meet his family—because there’s only one of them left: Nandu (Haasan), his insane fraternal twin. Nandu has been locked up in an asylum for his entire adult life after murdering their abusive stepmother when he was 12, and a visit to this snake pit is like a little daytrip to hell. Vijay hopes Nandu will be happy for him, but instead Nandu decides that Tejaswini is the reincarnation of their stepmonster, calls her a whore, and bites off a chunk of concrete and spits it at her.

Aalavandhan

Vijay hustles Tejaswini away, but Nandu’s convinced that he needs to rescue his twin from the grasping talons of Tejaswini. He breaks out of the asylum and makes for the city, leaving his medication, the booby hatch, and several corpses in his wake. Away from his meds, he turns to heroin as a stopgap sedative, and his head flies off into la-la land, leading to the flick’s most dizzying musical number: a long, dark night of the soul that starts with an encounter with Ronald McDonald, continues with some self-mutilation, and ends with a dance number with a rain goddess. Hallucinations crack open Nandu’s skull and force themselves onscreen in Technicolored smears: flying fairies, lethal female killbots, and televisions that spark to life with malevolent intent. Confused by the world around him, Nandu calls his brother to come pick him up and put him back in the slammer where at least animated trolls won’t poke him in the nose. But when he hears Tejaswini’s voice on his bro’s answering machine, it flips that killing switch in his head and he’s back on the job.

Pitiable and predatory, his fevered brain rotten with delusions, Nandu is no slick serial killer talking about Chianti. Instead, he’s a slave to his psychopathology, 300 pounds of solid muscle, with a voice like hot gravel, who bursts into helpless tears when he realizes the world outside his institution is too much for him to handle. Jam-packed with action scenes, musical numbers, hallucinations, and car chases, Aalavandhan was dismissed by journalists as a drug-addled mess, which is accurate, but hardly a reason not to watch.

For all the screaming metal, gruesome knife work, and end-times grudge matches, it’s Kamal Haasan’s jaw-dropping double turn as Nandu and Vijay that makes the movie. Nandu is truly insane with no rhyme or reason for his behavior, but Haasan also keeps track of the abused kid who became a killer adult. He’s pathetically at sea in the modern world, unable to navigate social interactions, and he kills people because he doesn’t know what else to do with them. In a harrowing mid-movie flashback we learn what happened to Nandu and Vijay to make them psychotic. That’s the poisoned center of this toxic Tootsie Pop: Kamal Haasan believes that both men are psychopaths, both are sadists and both were irredeemably warped by their childhoods. His point, written in dead bodies, is that it’s just pure chance that one little boy grew up to put on a soldier’s uniform, and one grew up to be put in the nuthouse.

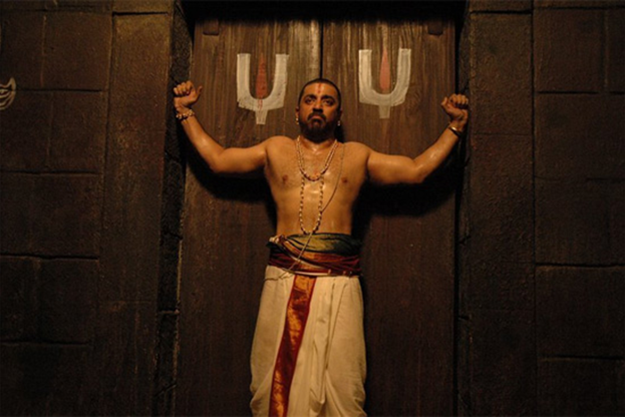

Virumaandi

Haasan’s next major film (after several box-office-friendly comedies) was Virumaandi (04), an anti-death-penalty movie centered around a land dispute in a small village. A documentary crew shows up at a prison and interviews Kothala Thevar, a man serving a life sentence for his role in a village conflict that left 24 people dead. He puts all the blame on Virumaandi, who becomes the documentarian’s next logical interview subject. Up until now, the movie has been framed as a found-footage documentary, but Haasan plays Virumaandi like a force of nature and his performance totally hijacks the film’s structure, bending it around his showcase. His Virumaandi is a rural folk god made flesh, like Rooster Byron in Jez Butterworth’s Jerusalem. He’s a massive man of the people, connected to the earth in a way Kothala will never be. He’s also a guy who inherits the last fertile land in the village, and we get led through an increasingly tangled plot to frame Virumaandi for murder and steal his land.

But the plot complications aren’t the point—this is a movie that revels in physicality. From a village game of Jallikattu (man vs. bull wrestling!) to a final prison riot, the movie feels like an extension of Virumaandi’s stocky, muscular body—vital and alive, rude and rustic. The early festival song “Andha Kandamani” is full of raw, rough voices, shouted choruses, fire, goats being led to sacrifice, heavy percussion, chubby half-naked man-bodies, and impressively ragged choreography. The goal of the film is to raise some kind of primal spirit from out of the dirt of Tamil Nandu’s villages and embody it in Haasan’s Virumaandi.

Since then, Haasan has starred and directed his fair share of hits and flops, the most insane of which is Dasavathaaram (08). Spectacle doesn’t even begin to describe it. The flick starts in hyperbolic fashion with Kamal Haasan winking at the audience before his credit hits the screen: “Kamal Haasan, UNIVERSAL HERO.” Then it becomes a gonzo version of Cloud Atlas in which Haasan plays 10 different roles, including President George W. Bush, a redneck hit man, a Japanese Judo master, a giant, an elderly woman, and a 12th-century priest. The first scene is set in the 1100s, as Haasan is captured by his enemies during a religious conflict and flogged, then hung up by hooks and swung out over a crowd while singing the first musical number—all before being chained to a stone idol, dumped in the ocean, and eaten by a shark.

Dasavathaaram

Jump to the modern day, as a reluctant bioengineer, Govind (Haasan again), steals a new bioweapon that is “more dangerous than AIDS” and goes on the run. On his tail is Fletcher (also Haasan) a bleach-blond Caucasian hit man with a soul patch who takes a helicopter to the high-rise where Govind is hiding, shoots a crossbow through the window, then gets in a kung fu fight with a survivor of Hiroshima, while Govind escapes onto the ledge. The whole scene ends with a cruel joke and a slit throat.

There’s an unembarrassed quality to the movie, despite its shoddy make-up, bad CGI, and lowbrow comedy. As long as everything keeps moving, everything is all right. Even a slapstick scene that ends with a character getting gruesomely impaled on an iron bar feels like a harmless lark. There are numerous effective touches (like a passing train’s lights forming a flickering halo behind a praying character’s head) and Haasan gets to indulge his taste for giant car crashes. His performances are constrained by truly awful make-up that gives his many faces all the emotional flexibility of wooden blocks, but his Fletcher is a sharp and funny performance, and you can’t hate a movie that contains the immortal line: “And this is Dr. Sethu, chief scientist found in a garbage can.”

Haasan enjoys the challenge: the stunt performance, the ridiculous make-up, the plot so deeply objectionable there’s no way anyone can pull it off. But he’s an insanely talented actor in a way a lot of South Asian stars are not (I’m looking at you, Rajinikanth), and any gaps in his movies he plugs with his charisma.

The climax of Dasavathaaram involves a rock concert, a motorcycle chase, a child’s birthday party, a helicopter, the president of the United States trying to nuke India, a judo battle on the beach, another helicopter, a musical number, and the deadly tsunami of 2004. By the time you reach that ending—via speeches about God, lectures on chaos theory, and digressions on international relations and love—it all seems to make some kind of perfect sense.

Grady Hendrix is a novelist and one of the founders of the New York Asian Film Festival. He writes on Asian film for Variety, Sight & Sound, and more.