Frank at 100: Sinatra on Screen

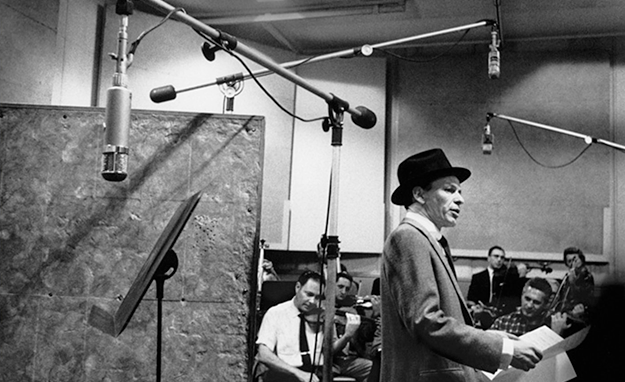

The Man With the Golden Arm recording session, 1955

When I was 17, it was a very good year—though I was probably closer to 14. Like any discerning middle-schooler in the late Nineties, I listened to Frank Sinatra records (all right, CDs) until I knew them backwards and forwards, as even my untrained adolescent ear could appreciate how Frank’s incomparable phrasing made a lyric like “I’m sure that if I took even one sniff, it would bore me terrif—ic’ly too” sound as conversational as if he were describing his lunch. I still bear the scars for my allegiance: during one contentious family road trip my parents could no longer endure the fourth disc of The Best of the Capitol Years and cut the music, leaving me no choice but to exit the moving vehicle and catch my heel under the rear tire. The result was a night in the ER and several weeks on crutches.

The only part of that anecdote that elicits a twinge of remorse is the fact that the objet d’art was The Best of the Capitol Years, disc four, and not one of his delicately arranged concept albums that address phenomena like loneliness (In the Wee Small Hours) or world travel (Come Fly with Me) with forethought to the ordering and interrelation of songs. Box sets might have debatable value as gateway tools, but at the same time they serve to collapse, conflate, and streamline their contents. Said compendium had the boorishness to follow Rodgers & Hart’s bawdy, riotous “The Lady Is a Tramp” with Cole Porter’s brooding, tormented “Night and Day,” producing an admiration for Sinatra the vocalist but not for Sinatra the master of mood. This may be the reason so many of us picture him standing before a mike with hat cocked and collar undone, singing about love in the most generic sense, but tend not to acknowledge his gifts as a storyteller, his ability to transport us, suspend us and relieve us as only fully realized artists can. (Sinatra, who was born 100 years ago this December, died in 1998.)

Ocean’s 11

If we take a fondly reductive view of his musicianship, our collective stance on Sinatra the actor is even more monolithic. We may recall him being feisty in an army uniform or dancing in a sailor suit, but more likely it’s his shenanigans with Dean Martin and the rest of the Rat Pack in Ocean’s 11—perhaps planning to heist a Vegas casino (the same one where they’d perform after wrapping the day’s shoot). This simplification is grossly unfair to the actor Frank Capra claimed could be the best who ever lived if he’d give up his singing and develop his screen presence. An Academy Award, two Golden Globes, and three stars on the Hollywood Walk of Fame (one for motion pictures) tell the real story.

Like the singer/protagonist of “It Was a Very Good Year,” Sinatra the actor weathered changes with the passing seasons. Following a few walk-on roles and a cameo as himself, he made his starring debut in 1943’s Higher and Higher, playing the boy next door who serenades Millie (Michele Morgan) with lovely McHugh/Adamson songs like “I Couldn’t Sleep a Wink Last Night.” Sinatra’s image at the time was the juvenile bandstand singer whose soulful crooning made bobbysoxers swoon, and studios rushed to capitalize by casting him as shy, sensitive young men. It’s truly jarring to watch these early appearances, knowing he would evolve into the face of Kennedy-era masculinity (“broads” and “mice” being his favorite distaff descriptors), but the fact remains that he spent his first decade in film playing tongue-tied bumblers, often pursued by aggressive females. On the Town (49) finds cabbie Betty Garrett virtually shanghaiing sailor-on-leave Frank, who beseeches her to take him to defunct attractions like the Hippodrome while she tunefully insists that he “Come Up to My Place!”

Take Me Out to the Ball Game

On the Town was the last of three postwar musicals Sinatra made with Gene Kelly, after Anchors Aweigh (45) and Take Me Out to the Ball Game (49)—his most gainful pairing of the period. In each, however, Kelly is the worldly-wise roué who takes callow Frank under his wing. It must be observed that Sinatra commits entirely to these earnest characterizations, however uncomfortable it may have been as a 35-year-old father of three to play every scene with one foot in his mouth. He’s palpably invigorated in the “Yes Indeedy” number from Ball Game, where he and Kelly, as the star players of a baseball team called The Wolves, swap tall tales of conquest and the farcical extremes of their paramours’ devotion. (The buoyant execution of the song belies some genuinely macabre lyrics by Comden and Green: “Her teachers wouldn’t pass her, so she just turned on the gasser, now the sweetest gal at Vassar’s in the cold, cold ground.”)

The next years were lean ones for Sinatra, forced to take roles in downright embarrassing films, the nadir being 1948’s infamous flop The Kissing Bandit. His teenage fan base deserting him, Sinatra was ranked by Down Beat magazine as less popular than singers Billy Eckstine, Frankie Laine, and Bing Crosby. Salvation came in the role of Angelo Maggio, a conniving, ill-fated Italian-American private stationed at Pearl Harbor days before the attack, in Fred Zinnemann’s 1953 adaptation of James Jones’s novel From Here to Eternity. Rumors continue to surround the casting of Sinatra in a part that had been earmarked for Eli Wallach—indeed, such speculation fueled the Godfather subplot involving Johnny Fontaine, a washed-up crooner afforded a coveted role in a war film only after the producer gets word from the horse’s mouth. In all likelihood, though, Sinatra’s casting owes to the lobbying efforts of then-wife Ava Gardner, and to his willingness to work for the bargain sum of $1000 per week.

![Title: FROM HERE TO ETERNITY ¥ Pers: CLIFT, MONTGOMERY / SINATRA, FRANK ¥ Year: 1953 ¥ Dir: ZINNEMANN, FRED ¥ Ref: FRO006EZ ¥ Credit: [ THE KOBAL COLLECTION / COLUMBIA ]](https://www.filmcomment.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2015/07/fromheretoeternity2.jpg)

From Here to Eternity

Watching him play Maggio, you begin to see what Capra meant. He acts like a house on fire—manic, uproarious (“Only my friends call me little wop!”), spontaneous (an improvised bit from his screen test where he throws grapes like dice features into the finished film), and ultimately heartbreaking. He credits co-star Montgomery Clift with guiding him through his dramatic scenes, particularly the aftermath of Maggio’s run-in with a sadistic sergeant played by Ernest Borgnine, and Sinatra’s brazenness complements Clift’s introspection in their shared scenes. He even recorded the title song, appearing in the film only instrumentally but released as a hit single by Capitol Records, who signed a contract with the professionally rejuvenated Sinatra that would comprise most of his best-loved recordings.

Riding high after Eternity, Sinatra took charge of his screen image. Here, truly, is where he transcends the flask-and-fedora archetype: In Otto Preminger’s taboo-smashing The Man with the Golden Arm (55), his turn as ex-con Frankie Machine, a junkie on Chicago’s North Side trying to kick his heroin habit and turn over a new leaf, is a study in clammy desperation, his swagger disintegrating as outside forces vie for control of his weakened will. In preparation Sinatra visited rehab clinics and closely observed addicts in the throes of withdrawal. No actorly smokescreens are employed in the cold-turkey scenes, among the most harrowing ever filmed. The result was another Oscar nomination for Sinatra, proof that his muscular work in Eternity was no fluke. Subsequent turns as nightclub entertainer Joe E. Lewis who runs afoul of the mob in the underrated The Joker Is Wild (57) and a cynical GI facing hometown hypocrisy in Vincent Minelli’s Some Came Running (58) round out a string of Fifties achievements comparable to the best of his contemporaries.

![Title: MANCHURIAN CANDIDATE, THE ¥ Pers: SINATRA, FRANK / HARVEY, LAURENCE ¥ Year: 1962 ¥ Dir: FRANKENHEIMER, JOHN ¥ Ref: MAN097CQ ¥ Credit: [ UNITED ARTISTS / THE KOBAL COLLECTION ]](https://www.filmcomment.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2015/07/Manchuriancandidate1.jpg)

The Manchurian Candidate

In 1962 Sinatra headlined arguably his greatest film, John Frankenheimer’s The Manchurian Candidate. Co-stars Laurence Harvey and Angela Lansbury enjoy showier roles in this definitive Cold War thriller, but Sinatra supplies the bassline. As the platoon commander who suspects that one of his men was brainwashed by Communists, Sinatra is the narrative foundation and audience surrogate. Certainly his iconic status played a role, too; seeing this paragon of American prowess give way to fevered paranoia summons more unease in viewers than pages of rhetoric could hope to do. And despite some staggering demands in exchange for his participation (half the film’s $2 million budget as his salary, all his scenes shot up front), Sinatra’s enthusiasm and generosity were noted by all participants, particularly writer George Axelrod, who called him “lyrically sensitive . . . magic” and “a dream to work with.”

The same could not be said for most of his concurrent efforts. Between 1960 and 1964 he starred in four well-compensated hangouts with his fellow Rat Packers, the nominal best being Robin and the 7 Hoods (64)—all epitomizing his progressively blasé approach to acting. Then came a run of glossy whodunits and labored comedies like the execrable Dirty Dingus Magee (70), about which Roger Ebert observed: “I lean toward blaming Frank Sinatra, who in recent years has become notorious for not really caring about his movies. If a shot doesn’t work, he doesn’t like to try it again; he might be late getting back to Vegas.”

Contract on Cherry Street

But after a lengthy hiatus, he proved to have one last trick up his sleeve. In 1977, now an elder statesman, Sinatra made his TV movie debut with the gritty, violent Contract on Cherry Street. Playing a police detective fed up with departmental corruption and mob rule, Sinatra’s jadedness suited the material like a shot of his beloved Jack Daniels at the end of a long day. His scenes with wife Verna Bloom and partner Martin Balsam are duets of world-weary naturalism. Having begun his career playing soft-spoken naïfs, Sinatra completed his arc with lived-in grace. Not altogether surprising, given that his headstone reads: “The best is yet to come.”

The “Frank at 100” series screens July 24 to 26 at the Film Society of Lincoln Center. The exhibition “Sinatra: An American Icon” is on view at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts through September 4.