Films of the Week: Locarno Sex Romp Edition!

Wet Woman in the Wind

Of late, Western audiences may have formed the impression that Japanese cinema has become somewhat tame. The most prominent titles on the recent U.S. and U.K. release schedule, and in the Cannes official selection, have been accessible, unthreatening works from Hirokazu Kore-eda, these days making pensive but benign family dramas such as Our Little Sister and this year’s After the Storm and Naomi Kawase, whose Sweet Bean was every bit as soft-centered as the pancakes that were its theme. Only Sion Sono’s rambling trash-aesthetic sagas have continued to provide at least some cult visibility for the extreme.

With this in mind, it was a pleasure to discover that two of the most outré films in Locarno this year—where, all told, the bizarre factor has been bracingly high—were from Japan, both providing a blast of energy. With Wet Woman in the Wind and the zappily named Destruction Babies, we’re in the realms of sex and violence respectively, but also in a zone of energy, inventiveness, provocation, and perverse fun. They’re not the deepest or most satisfying films here, but Locarno audiences aren’t likely to forget them in a hurry.

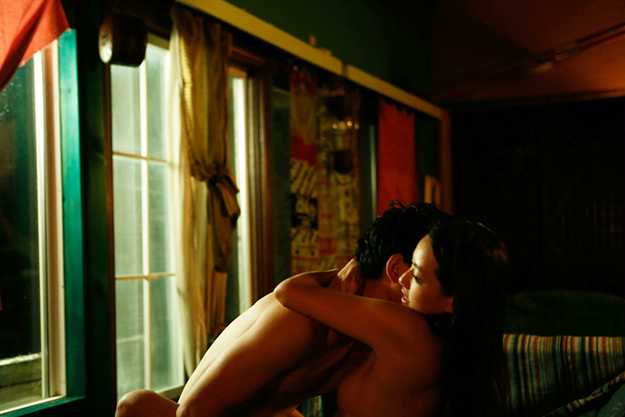

Wet Woman in the Wind is a curious proposition—a formal genre exercise with energy to spare, and a cheerfully dirty mind. Written and directed by Akihiko Shiota, best known for low-key drama titles such as Harmful Insect (01) and action blockbuster Dororo (07), Wet Woman is one of a series of films commissioned by the Nikkatsu Corporation to celebrate the 45th anniversary of their “Roman Porno” series of sex films, which originally ran from 1971 to 1988. Shiota is a connoisseur of the series, having written an appreciation of director Tatsumi Kumashiro, whose 1973 Lovers Are Wet also showed here as a side order to Wet Woman. Shiota makes no bones about having tossed off his film in a hurry (I’m sorry, but innuendo seems more than appropriate under the circumstances), the terms of the commission stipulating a low budget, limited preparation time (writing and filming took only a week each), and a certain amount of relatively chaste, i.e. largely above the waist, nudity.

Wet Woman in the Wind

Wet Woman is essentially an essay in nudie screwball, starring Yuki Mamiya as a variation on that dreaded romcom archetype the Manic Pixie Dream Girl. At least, she’s manic, but the traditional role of vibing up the hero’s emotional life is hardly the main concern of this furiously libidinous heat-seeking missile of a femme. She first grabs the attention of reclusive playwright Kosuke (Tasuku Nagaoka) by riding her bike into a river, then promptly leaping onto his shoulders (one of her favorite foreplay positions, it subsequently turns out) and refusing to let go. Kosuke remains indifferent to her charms at first—which only fuels the chagrin of her café-owning boss, who’s got the hots for her something rotten.

There’s not much of a plot. Kosuke’s lean-to shack is visited by his theatre director ex and her retinue of eagerly polite young white-shirted actors, who run through a scene on the spot—which Shiori promptly contrives to liven up. The ex makes a move on Kosuke, but things are just warming up when Shiori decides that it’s her show, Kosuke ending up with nothing but a donkey kick. Eventually, everyone gets in on the act, in various combinations and through a series of goofy sight gags—cue our old friend, the furiously wobbling camper van. The culminating moment—oh all right then, climax—comes when Kosuke’s lean-to collapses, and Shiori just cuts herself a slit in the canvas roof and carries on what she’s doing (that is, doing Kosuke).

Wet Woman manages to be almost demurely tame—although Mamiya’s wild moaning certainly knows no volume control—but the keynote is a sort of frenzied circus-like energy, with the two leads constantly engaged in feisty erotic combat, tussling with other, clothed and naked, as much as actually making love. It’s an astonishingly athletic performance from both Mamiya and Nagaoka, and an absurdly enjoyable film. The slapstick goofiness builds up from a quiet beginning to an altogether apocalyptic climax, as if the force of desire were rolling thunder, or a form of epidemic, with Shiori’s libido joyously infecting everyone who comes into her orbit. She’s like the woman in the Irving Berlin song, starting a heat wave by letting her seat wave.

Destruction Babies

The same epidemic logic applies to male violence in the genuinely extraordinary Destruction Babies, by Tetsuya Mariko (Yellow Kid, 09). This story put me in mind of Fight Harm, the film in which Harmony Korine intended to go around randomly picking fights and filming the result (reputedly abandoned because he ended up getting injured too much). In fact, the film is based on a true incident that Mariko heard about while working in the city of Matsuyama; Mariko also took inspiration from the city’s autumn festival, where teams carry portable shrines around and, by all accounts, get into quite violent clashes with each other. Mariko was fascinated, he says, by the city’s mixture of serene landscape and sudden explosive violence. It’s not hard therefore to see the film as a state-of-the-nation comment on surface calm and underlying rage in contemporary hard-times Japan.

The setting is a dull port town where we first see 18-year-old Taira (the somewhat older, and older-looking, Yuya Yagira) getting beat up by a local gang. Cruising for bruisings (his own and others’) is Taira’s delight, and the film follows him to a nearby urban precinct where he gets into a series of scraps, and where his own pugnacity quickly transmits itself to everyone he tangles with; Taira is always left battered and bloody, and grinning in disturbing rapture, but he always rises again, increasingly juggernaut-like. Things take a strange turn when Taiga acquires his own disciple in violence, sneering brat Yuya (Masaki Suda), who leaves Taira by comparison looking like somewhat simply committed to a pure, almost joyous expenditure of male energy. Eventually a young club hostess and shoplifter, Nana (Nana Komatsu, soon to be seen in Martin Scorsese’s Silence), gets kidnapped by the duo, as the film takes a hoods-on-the-run turn; rest assured that she eventually gets to pull off the act of violence that will most make you wince.

Destruction Babies is an immensely strange film: everything seems to be heading, judging from all the hints, towards an apocalyptic payoff in which the shrine festival will explode on screen. As it is, the festival is heard in the background and barely glimpsed, while an eerie open ending shows Taira transmuted into a sort of transcendental god of brutality.

Destruction Babies

The film is no doubt destined to be pigeonholed as the Japanese Fight Club, and you have to assume that it’s nodding to Fincher’s film to some degree. But it also reminded me, in the way that its protagonist throws himself body and soul into his physical and existential transformation, of Shinya Tsukamoto’s Tetsuo: The Iron Man (89). The sheer relentlessness of the mayhem is both mesmerizing and exhausting, although dramatically the film proves to be a lot more subtly modulated than you might expect. Helping sustain the sense of mystery is the super-laconic performance of Yagira, who at 14 won Best Actor in Cannes for his part in Kore-eda’s Nobody Knows. Here he’s turned into a menacingly unknowable figure, with a brutish cool somewhere between Brando and Joe Shishido, the shades-wearing hero of Seijun Suzuki’s Branded to Kill.

The epidemic theme comes unstuck in a burst of literalness towards the end, as the screen fills with signifiers of the episode’s explosion as an online phenomenon. But for the most part, Mariko has created something that feels genuinely like a controlled, sustained explosion of on-screen hysteria. Destruction Babies is frenetic, brutal and weirdly cathartic—and you can bet that Mariko wants us to feel uncomfortable at letting ourselves get caught up in it. Because—nervous giggles and all—you do, you definitely do.

Jonathan Romney is a contributing editor to FILM COMMENT and writes its Film of the Week column. He is a member of the London Film Critics Circle.