Cinema ’67 Revisited: A Fistful of Dollars

In my 2008 book Pictures at a Revolution, I approached the dramatic changes in movie culture in the 1960s through the development, production, and reception of each of the five nominees for 1967’s Best Picture Academy Award: Bonnie and Clyde, The Graduate, In the Heat of the Night, Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, and Doctor Dolittle. In this biweekly column, I’m revisiting 1967 from a different angle. As the masterpieces, pathbreakers, and oddities of that landmark year reach their golden anniversaries, I’ll try to offer a sense of what it might have felt like to be an avid moviegoer 50 years ago, discovering these films as they opened.

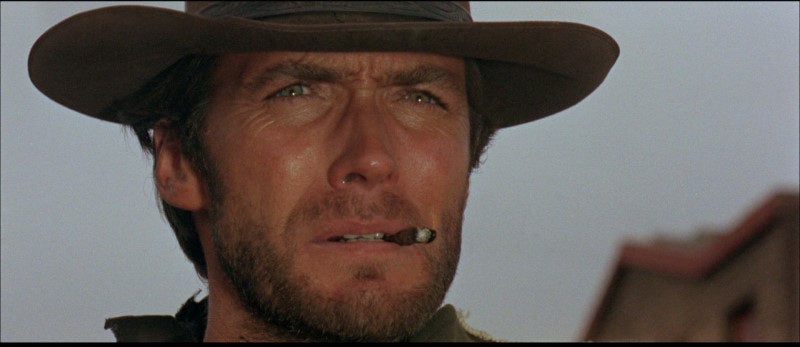

In the early spring of 1964, Clint Eastwood, a TV actor looking to break into movies, signed a contract to spend his sixth-season hiatus from his sidekick role on the CBS series Rawhide in Italy and Spain, making a Western called Magnificent Stranger for a novice director, Sergio Leone. Leone knew of Eastwood only because he had happened to see the 91st episode of Rawhide, “Incident of the Black Sheep,” and was happy to get him at the bargain-basement price of $15,000—which was $10,000 less than Charles Bronson had demanded.

It was a gamble for both men—and two years later, one that did not appear to have been particularly wise. In Richard Schickel’s Eastwood biography, the star recalls that when producers saw the dailies, they responded, “Jesus, this is a piece of shit.” Eastwood went back to his TV show, and even though he returned to Europe the following summer to make a second picture for Leone, he assumed that neither movie would ever be seen in America. Originally, Leone didn’t even put his name on the first films—since Italian-made Westerns were more marketable to audiences if they appeared to come from America, he billed himself as “Bob Robertson.”

Not that American Westerns, in 1967, were a particularly hot commodity—or a commodity, period. Over the last decade, network TV shows—not just Rawhide, but Wagon Train, Bonanza, Gunsmoke, The Virginian, and Cheyenne—had appropriated the genre, tamed it, and replaced its majesty, danger, and high stakes with familiarity, domesticity, and repetition. This was not so much murder as assisted suicide, since by the mid-1960s, big-screen Westerns had pretty much done themselves in. Other than a few elegiac gestures from John Ford and Howard Hawks, the Western had offered little of value—giant, heavy-limbed misfires like The Alamo and How the West Was Won, spoofs like Cat Ballou, and halfhearted quasi-modern takes like the James Garner–Sidney Poitier team-up Duel at Diablo all seemed to suggest a genre on its last legs, expiring under bright-blue Technicolor skies on prairies and mesas that audiences could probably have traversed blindfolded by then.

It’s hard to overstate what a sharp contrast Bob Robertson’s Magnificent Stranger—or, as it came to be known, A Fistful of Dollars—offered to unsuspecting audiences. Crude, cheap, and brutal, with dim lighting, laughably casual dubbing, and an almost wordless storytelling style stripped down to the most elemental, stark visual gestures, except when it exploded into baroque violence, Fistful was, both literally and metaphorically, the darkest western to have reached American screens in years, a bleak story of a taciturn gunslinger who plies his trade in a hellish town whose most cheerful resident seems to be the constantly employed coffin builder.

If you look on IMDb, Fistful’s release date is listed as 1964, with For a Few Dollars More following in 1965. But to American moviegoers at the beginning of 1967, the movies did not exist, and Eastwood was, at that point, not even a workaday TV actor—his show had been canceled. Leone’s two films had shown all over Europe, where their star was starting to develop a cult following, and on U.S. Army bases, but they had never found their way to U.S. movie theaters.

That was all about to change, thanks to the shrewd intervention of United Artists, which had recently experienced blockbuster success with its first four James Bond films and was eager to create a new franchise. In early 1966, UA agreed to finance the third and most elaborate Eastwood/Leone collaboration; later in the year, the company struck upon a marketing gimmick. It would acquire Leone’s first two movies and roll them out early in 1967—A Fistful of Dollars in February and For a Few Dollars More in May—and package them as the first two installments in a trilogy (although the films had not been written or conceived that way and there is no plot continuity between them) about a gunslinging “Man with No Name” (he actually had a name, but that was easily gotten rid of). At the end of 1967, UA would then release the third movie, which the New York Times reported would be called Good, Ugly and Evil. Variety later corrected that, saying that “the title of the third film would be changed to get ‘Dollar’ into it.”

A few kinks had to be ironed out: The films needed to be redubbed (Eastwood, fortunately, had kept notes about his own dialogue, since he knew Leone’s crew would just throw their copies away), and a financial settlement had to be reached with the producers of Akira Kurosawa’s 1961 Yojimbo, of which A Fistful of Dollars is essentially an uncredited remake. UA didn’t have high expectations for Fistful—the company thought the series might start to take off with For a Few Dollars More—and the New York Times did not help, with Bosley Crowther calling the first movie “cowboy camp of an order that no one has dared in American films since, gosh, Gary Cooper’s [1929] The Virginian’ and dismissing Eastwood as “simply another fabrication of a personality” in a movie that he called “egregiously synthetic but engrossingly morbid.” Crowther went on to inveigh against the film’s morals in a Sunday column, bemoaning “the dismally mercenary attitude” of its hero, who comes into a town riven by two warring factions and who “isn’t even committed to the triumph of either side…It is a dangerous overturning of the apple-cart, and…it is likely to do some lasting harm.”

Give Crowther credit for at least guessing correctly that the movie would have real impact. Although Fistful underperformed in New York, nationally it grossed more than 40 times the $100,000 UA had invested to purchase it, and the following two films did even better. Eastwood’s lone gunman, operating above and apart from the law, narrowing his eyes at everything around him in hostile contempt, and living by a self-generated moral code rather than one imposed by the uncivilized society around him, proved the perfect antihero for a generation that felt vast mistrust for organized authority, armed or not. And audiences who didn’t give a thought to politics but just wanted to see bad guys get shot could get satisfaction from this one-size-fits-all-ideologies maverick as well.

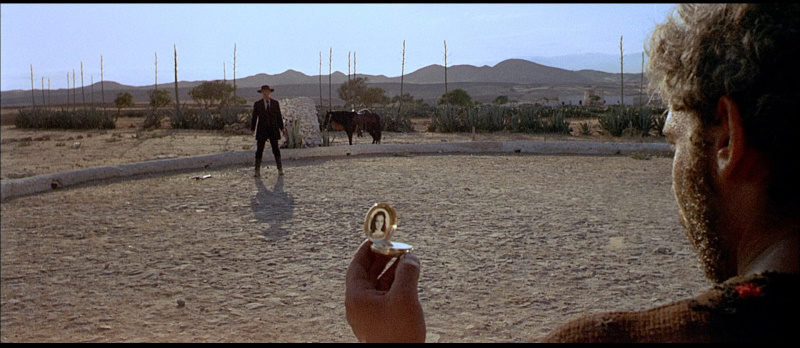

In a year in which The Dirty Dozen and Bonnie & Clyde would soon shatter all rules about acceptable screen violence, the Leone films helped set the table; today, directors and movie lovers view them as milestones in the very genre that Crowther was sure they would help to destroy. And fifty years later, it’s particularly rewarding to watch them quickly in sequence. Back-to-back-to-back, they’re a study in escalating ambitions; Fistful was made for just $250,000 and looks it, clocking in at a lean 100 minutes, For a Few Dollars More had three times the budget and runs for 132 minutes, and various cuts of The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (they never did get ‘Dollars’ into the title), which cost $1.2 million to make, run anywhere from 161 to 179 minutes, with Ennio Morricone’s score reaching a peak of orchestral ecstasy that is a long way from the lean, ambient soundscape he created for the first film. By then, Leone’s visual approach, so bare-bones in Fistful, had flowered into something almost operatic; watching in sequence, one gets the sense that he felt he had to burn the western to the ground first in order to build something new and spectacular two movies later.

The quasi-trilogy did not launch the “spaghetti western” genre—Time noted that by 1967, more than 180 “eastern westerns” had been made—but it did bring a new, more pared-down, iconographic, and blood-soaked take on the Western to American shores and replace some of the genre’s moral certitude with a dose of Vietnam-era cynicism and nihilism. (One can draw a pretty straight line from Leone to Sam Peckinpah’s 1969 The Wild Bunch.)

After 1967, Eastwood’s and Leone’s careers diverged swiftly—perhaps in part because Eastwood got tired of Leone disparaging his acting ability. Although Leone would live 20 more years, he would direct only three more movies (for his next, Once Upon a Time in the West, he finally got the star he had wanted for years, Charles Bronson). Eastwood, for his part, never looked back—in the year after The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, he made Hang ’Em High, Coogan’s Bluff, and Where Eagles Dare, securing his perch as a movie star. His status as a critic’s darling would be longer in coming; in 1967, he was greeted with perplexity, with culture writer Judy Stone shrugging, “Why has ‘Fistful’ become the latest craze? Darned if I know. I sat by myself in the uneasy stillness of a screening room… mystified… well, if the French can make some kind of genius out of Jerry Lewis…” She asked Eastwood if he understood it and the 36-year-old actor’s reply hinted at the savvy auteur to come: “Looking back,” he told her, “I think we were better off for having had an offbeat director. The conventional guy would have either tamed the picture down to another backlot Western or taken the satiric comment and made it slapstick and unpalatable. This way, it appeals to someone looking for that kind of comment, but it doesn’t alienate the viewer who wants an action-packed film.” By then, Eastwood had already made one decision he would never reverse: One particularly grueling day on the set of The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, he said he’d had it with Leone’s way of making pictures. “Never,” he told Eli Wallach, “trust anyone [making] an Italian movie.”

How to see them: All three movies stream on Amazon and iTunes and are available on DVD and Blu-ray.

Mark Harris is the author of Pictures at a Revolution: Five Movies and the Birth of the New Hollywood (2008) and Five Came Back (2014).