Festivals: Berlin

Gog

The repertory and restoration beat on the festival circuit is the coward’s path—I know, because I usually opt for it. When faced with a competition lineup and sidebars comprised of unknown quantities with only interchangeable, postage-stamp-sized stills of actors standing in a sylvan glade to distinguish between them, I’ll take an old reliable like a 16mm print of The Ballad of Cable Hogue (1970) with Swedish subtitles every time.

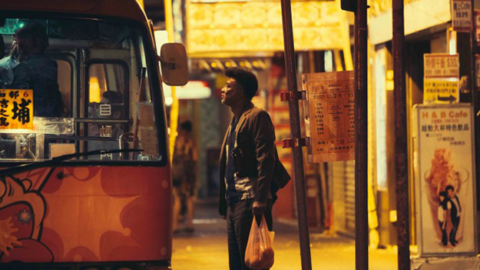

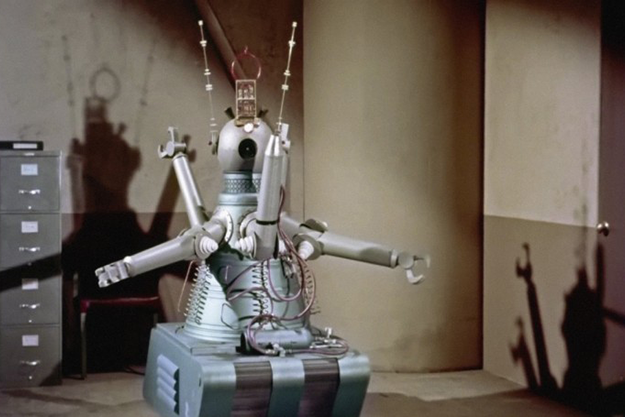

So, despite the fact that I was physically present at the Berlinale this year, I’m afraid that I can tell you nothing about Golden Bear winner On Body and Soul, other than the fact that it’s Hungarian, and that several people urged me to see it, usually after asking “Do you like Toni Erdmann?” I can, however, discourse at length on the subject of the new digital RealD restoration of Gog (1954), an independent science fiction production helmed by the somewhat-less-than-distinguished director Herbert L. Strock, in which the inhabitants of a subterranean government facility are terrorized by what appears to be the overseeing computer system run amok. A 15-day wonder starring Richard Egan and Constance Dowling, in her last film before marrying the film’s producer, Ivan Tors, Gog is mostly of interest for a couple of amusing 3D effects—a belabored bit involving a windshield wiper clearing ice crystals, for example—and as a precursor of the “rise of the machines” narrative which would become more prevalent with ever-increasing singularity paranoia. (In this case the culprit isn’t a malevolent awakened computer intelligence, but a signal coming from a Russian plane hiding in the stratosphere.)

Gog was included in a well-stocked science-fiction sidebar, along with the unveiling of distant-relation Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991) in one of James Cameron’s coming-to-be-habitual 3D rejiggerings of past blockbusters—can’t wait until he gets to True Lies (1994)!—and what was certainly the strangest movie that I saw at Berlinale, Curtis Bernhardt’s Le Tunnel. That the Bernhardt film is a French-German co-production dating from the year 1933—and shot by a Jewish director for good measure—should be distinction enough, but added to this is the fact that it features a Francophone cast playing North Americans in an approximation of New York City built on a German soundstage, the cast featuring the ultimate Parisian, Jean Gabin, as a native Buffalonian with the improbable sobriquet “Allan Mac Allan.” The cast of the French version, I should say; Bernhardt simultaneously shot a German-language film, Der Tunnel, starring Paul Hartmann in the Mac Allan role, and the movie’s source material—a 1913 novel by one Bernhard Kellermann that imagined the digging of a Transatlantic tunnel between North America and Europe—was later adapted into a film in the U.K. in 1935. Amidst great silliness Gabin is still virile, gutty, and compelling, paired here for the first time with the tremulous Madeleine Renaud, later his co-star in two of Jean Grémillon’s finest movies, and it is hard to entirely write off a movie that calls for the star of La Grande Illusion to repeatedly pronounce the word “Cincinnati.”

Black Gravel

In 1933, as in 1913, the collective genius of Euro-American engineering was very soon to be put to less constructive pastimes than Mr. Kellermann’s undersea tunnel, and the lingering aftermath of the midcentury cataclysm is the subject of Helmut Käutner’s Schwarzer Kies (Black Gravel, 1961), a film every bit as gritty as the title implies. Released on the other side of the world within months of Shohei Imamura’s Pigs and Battleships, Käutner’s film has approximately the same setting and subject—a city in a defeated Axis nation dominated by the presence of a U.S. armed forces base, and the shadow economy of vice and theft that emerges around that base.

A documentary-style opening, recalling the approximately contemporary film-inciesta (film investigation) works then coming out of Italy, establishes the setting of Käutner’s film as the fictional village of Sohnen in the Hunsrück mountains of the Rhineland-Palatinate, and even concocts some demographic figures: the sleepy hamlet that once housed only a couple of hundred souls has now been swollen to six thousand, including a robust population of prostitutes there to serve the servicemen on leave. The central character is Robert (Helmut Wildt), a veteran of the Eastern front now working as a truck driver with various legally sketchy side-hustles, his current scheme consisting of padding his income by siphoning gravel from the construction of a landing strip on the base—under the opening credits we see him cavalierly discarding the corpse of a dead pet Dalmatian that’s just been smashed with a heaved rock, which pretty well sets the unsentimental tone for what’s to come. The building of the strip is being overseen by a middle-aged American contractor (Hans Cossy), whose wife, Inge (Ingmar Zeisberg), just happens to be Robert’s old flame. He immediately sets about trying to reignite the affair, skulking around while she unpacks decorative Hummel figurines and beer steins in her pristine living quarters, and dripping contempt all over her new, clean, comfortable middle-class life.

What’s immediately striking about Schwarzer Kies, particularly in contrast to the majority of films that Hollywood was producing at the same time, is its wholly unglamorous naturalism—there’s lots o’ listless and loveless screwing, destructive binge-drinking, and puking bar girls—and its palpable proximity to the underbelly of German society. Käutner was shooting on location in Lautzenhausen, home of the Hahn Air Base, and he recruited real American G.I.s for the film and shot in the real red-light district, where the jukebox is heard blaring rockabilly for the troops and Volkstümliche marches for a local peasant who drinks for free in exchange for leasing his barn to be used as a cabaret until he blurts anti-Semitic slurs at a proprietor who bears a concentration camp tattoo on his forearm. This unwelcome reminder of recent history raised the ire of Hendrik van Dam, then head of the Central Council of Jews in Germany, and this along with almost uniformly hostile reviews conspired to bury the film on initial release, though its reputation has grown steadily through the years, a process that should be expedited by the Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau-Stiftung’s restoration.

The Devil Strikes at Night

West German cinema between 1946 and the middle 1960s has for some time been represented—outside of Germany, at least—as a blank spot on the map of world cinephilia, the result of an all-too-successful public relations putsch by the so-called New German Cinema who, following the model laid down by the Nouvelle Vague, modeled themselves as a generation without parents, positioned against the establishment that they hoped to storm. (In both cases these attitudes would have more than a little to do with the disgrace of the war years, and a very justified sense of the parent’s generation being fatally compromised.) However, with events like the reappearance of Schwarzer Kies and Film Festival Locarno’s 2016 pointedly-titled revival program “Beloved and Rejected: Cinema in the Young Federal Republic of Germany from 1949 to 1963,” it appears that the old guard will finally have their day in court, introducing new viewers to such Adenauer Era pleasures as, say, Robert Siodmak’s The Devil Strikes at Night (Nachts, wenn der Teufel kam, 1957). The “Beloved and Rejected” catalog, incidentally, kicks off with reference to Käutner, who couldn’t win for losing—too radical for the newspaper critic, too tradition-bound for the young Turks: “In 1962 Schwarzer Kies and its Brechtian ballade opera companion piece, Der Traum von Lieschen Müller (1961), also staged by Käutner, shared the ‘Young Film Critics’ Award for the Worst Achievement by a Prominent Director,’ presented during the 8th West German Short Film Festival at Oberhausen—the occasion on which the Oberhausen Manifesto was read . . . Reading the criticism of Federal German films published in the intervening decade, one gets the impression that finding fault was the done thing and that to register any approval without raising objections was simply unimaginable . . . Nobody really seems to have liked this cinema other than the public.”

That being said, the other entirely indelible experience of my Berlinale came courtesy of a lion of New German Cinema, and the figure who solved the issue of the breach between uncompromised artistry and public acceptance by dissolving it, Rainer Werner Fassbinder. The work in question was a fresh restoration of Eight Hours Don’t Make a Day, a miniseries comprised of five feature-length episodes amounting to eight hours’ runtime produced by Westdeutschen Rundfunk, which aired monthly between October 1972 and March of ’73. Among non-German-speaking RWF aficionados the series has been something of a Holy Grail, for not only does it represent a hefty slab of (largely) unseen Fassbinder, but it dates from a pivotal moment in the director’s career—the creative rebirth that immediately followed his encounter with the Hollywood melodramas of Douglas Sirk, born Hans Detlef Sierck in Hamburg, which determined Fassbinder to attempt to reconcile the seemingly opposed traditions of intellectual experimental theater and emotional popular entertainment.

Shot in Cologne over a four-month period beginning in April, the series stars Gottfried John as a skilled machine tool factory laborer and Hanna Schygulla as his lover and then young wife, following the events of their workaday lives and those of their co-workers and extended families, including Luise Ullrich and Werner Finck, two seasoned and popular older actors from outside of his Antiteater repertory crew, who represent perhaps the most wholly lovable characters in the entirety of the Fassbinder universe. To do justice to Eight Hours Don’t Make a Day in this space would be impossible, so it will have to suffice to say that its emergence represents nothing less than the discovery of a vital missing link in the director’s filmography, one that may represent his clearest vision of an achievably, incrementally better world.

Eight Hours Don’t Make a Day

If Eight Hours Don’t Make a Day marks a populist turn by an artist who had up to that point been obscurantist, the 177-minute experimental behemoth ORG (1979) represents the exact opposite. Argentine director Fernando Birri had been a known quantity in progressive film circles since his 1960 moyen métrage documentary Tire dié, but the unexpected factor in ORG is the presence of Terence Hill (né Mario Girotti), the film’s “leading man” and producer, a spaghetti western star widely associated with the many, many films he made in partnership with Bud Spencer (Carlo Pedersoli)—movies that practically no North American is on familiar terms with, and which every continental European knows intimately. Inspired by Thomas Mann’s The Changed Heads, ORG is less a movie than a torrent of thin-sliced cuts and layered soundtrack dissonance; for sheer audience antagonism, it’s a work on a par with approximately contemporary works like Metal Machine Music or the films of Carmelo Bene. Legend has it that after the film’s premiere at the 1979 Venice Film Festival, Hill’s agent urged him to disavow it and return to more profitable endeavors like the safari comedy I’m for the Hippopotamus (1979), opposite Spencer. When that retrospective comes, I’ll be first in line.

Nick Pinkerton is a regular contributor to Film Comment and a member of the New York Film Critics Circle.