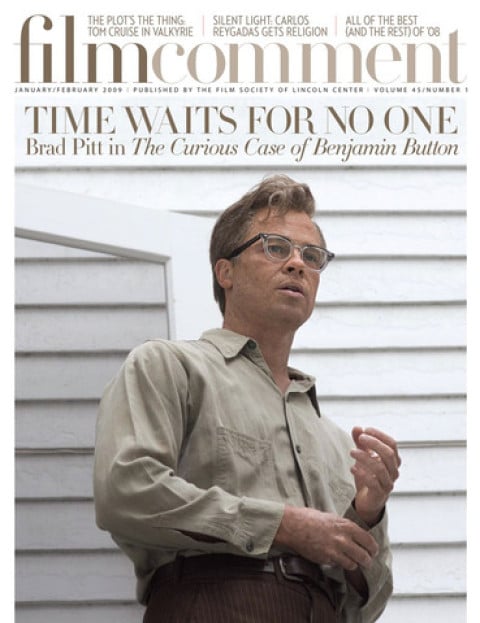

California Company Town

(Lee Anne Schmitt, U.S.)

Schmitt’s documentary surveys a series of towns that have been abandoned by the industries that created them from scratch. Empty warehouses, wastelands, deserted homes—ghost places whose misery is emphasized by a soundtrack of archival radio broadcasts celebrating American-style capitalism. In the same vein as Profit motive and the whispering wind, but better structured and less pious, it shows the last vestiges of industrial capitalism, the twilight of the American Dream.—Elisabeth Lequeret

Une catastrophe

(Jean-Luc Godard, Switzerland)

A great movie can never be too long, but can a masterpiece be disqualified for being too short? Commissioned by the 2008 Viennale, this 60-second festival trailer is not, in essence, a departure from, or improvement on, a hundred feats of ideogrammic montage from Histoire(s) onward. But it’s precisely as shard, fragment, and ultra-compressed dialectic that it scintillates—as swift and sure as a lyric by Celan. “A catastrophe/is the first/strophe of a poem/of love” weaves the text through a quotation field of sound and image, war and peace, ici et ailleurs, whose diamantine polish bespeaks a lifetime’s devotion to “beau souci” of montage, never so beautiful as here.—Nathan Lee

Cosmic Station

(Bettina Timm, Germany)

At the peak of Armenia’s highest mountain is a semi-abandoned Soviet research station dedicated to exploring outer space and searching for new galaxies through the detection of the radiation of stars being born. Timm’s short lyrically portrays the decay of this place and the philosophical humor of the aging scientists as they continue their work with seemingly nowhere else to go.—Irina Leimbacher

Crude Oil

(Wang Bing, China)

At 14 hours of super long-takes, Crude Oil is perhaps best experienced as an installation, which is how it was exhibited at the Marseille International Documentary Festival. Although viewing this unromanticized portrait of labor can be intensely claustrophobic as we watch workers at rest or half-asleep in their tea room, other passages show us the drilling and pumping platforms in the Gobi Desert, with their real-time rhythms. —Irina Leimbacher

Dernier maquis

(Rabah Ameur-Zaimeche, France)

Ameur-Zaimeche’s third feature, after Wesh Wesh (set in the banlieus) and Bled Number One (Algeria), is a major political film. It restores the complexity of critical questions such as the work of immigrants in France, the violence of class relations, and the role of religion. With great humor, the director casts himself as the boss of a small business named Mao, who builds a mosque on his premises, the better to control his employees. In the enclosed compound of the warehouse, the film constructs a vigorously dialectical narrative, while setting up a remarkable formal conceit in which the color red predominates. In sum, an original attempt at “fantastic realism.”—Frédéric Bonnaud

The Door of Ceuta

(Pedro Pinho & Frederico Lobo, Portugal)

Young Portuguese filmmakers undertake the journey of African immigrants heading for Europe, but in reverse. Ceuta is Europe-in-Africa, the place from which the rest of Europe becomes imaginable, but there are many steps, both forward and backward, chosen and imposed, before that. Beginning in Tangiers, moving to the area around the Algerian border where Morocco sometimes dumps its illegal African immigrants, then into the desert, and finally to the coast of Mauritania, Pinho and Lobo humbly engage with numerous Africans in this lucid, moving, and painful portrayal of what it means to take the immigrant journey today.—Irina Leimbacher

Elderblossom

(Volker Koepp, Germany)

A gorgeously shot documentary on the region of Kaliningrad (formerly in Prussia, part of Russia since 1945), where the adults seem to be either absent or alcoholics but the children thrive. Koepp, who has had a long career in East Germany, focuses almost exclusively on the children: their sense of play, resourcefulness, and gentle imagination make even this world of unemployment and adult despair seem a hopeful place.—Irina Leimbacher

Everlasting Memories

(Jan Troell, Sweden)

Adapting a novel by his wife based on the life of one of her relatives, Troell manages a complete portrait of the early 20th century. A young housemaid (Maria Heiskanen) with four kids and a dockworker husband wins a camera in a lottery. The device becomes a sanctuary and at the same time enables her to embrace everything about the new age. Revolution is afoot—in marriage, love, the mechanical image, in the industrialization of art, government, labor, and business. Stately, emotionally restrained, and filmed in images that seem printed on steam, the film crowns the career of Troell, who began as a photographer, and who is one of the few directors left who can bring motion to pictures.—Harlan Jacobson

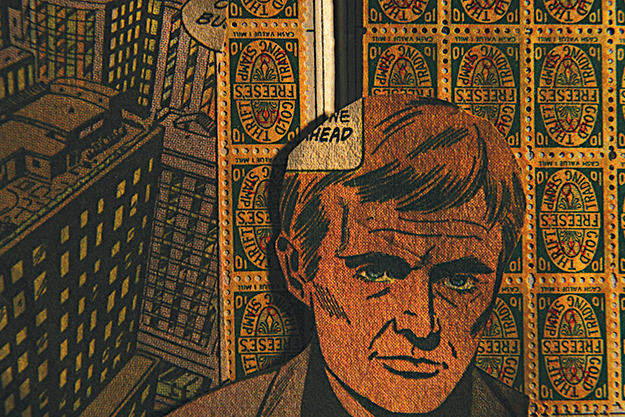

False Aging

(Lewis Klahr, U.S.)

It’s hard to believe that False Aging clocks in at under 15 minutes, given how powerfully it evokes passing decades punctuated by muffled eruptions of longing and regret. A button revolves around a clock—and the world moves with it. Klahr shares Joseph Cornell’s alchemical genius, but his collaged reveries cast deeper shadows and offer little magical protection from death and disappointment. The soundtrack draws on The Valley of the Dolls, Jefferson Airplane, and Lou Reed and John Cale’s Songs for Drella. As Cale channels Warhol, recounting a nightmare involving a snowy park under the stairs and anxieties about troubles real and imagined, a blond man peers at cityscapes, a skeletal hand snatches a fortune, and no-longer-redeemable trading stamps flutter by.—Kristin M. Jones

Helen

(Christine Molloy & Joe Lawlor, U.K.)

This debut feature follows on from Molloy and Lawlor’s series of “Civic Life” shorts, under their “Desperate Optimists” banner, extending its community-project agenda into an extremely spare mystery about a young volunteer who steps into the role of a vanished girl for a police crime reconstruction. Cast with nonprofessionals, the film’s measured syntax and visual language are closer to gallery video than art cinema, but Helen yields echoes of Bresson, Egoyan, and Antonioni, especially Blow-Up. A detached, sensitive, quietly unsettling essay on identity and aspiration, it’s not quite like anything else—certainly nothing else in British cinema.—Jonathan Romney

Un Lac

(Philippe Grandrieux, France)

The London Film Festival screening of Un Lac was delayed in an attempt to satisfy the director’s desire that the theater be made as dark as possible. Health and safety requirements prevented optimal sepulchral conditions, but the force and purity of Grandrieux’s film still shone “brightly.” This fable-like tale of a woodchopper, his beautiful sister, their blind mother, and a young interloper takes place largely in either swirling snow or complete blackout, with only Grandrieux’s painstakingly constructed soundscape—creaking trees, chopping wood, cracking ice—to guide us. The Exit lights stayed on, but we were still lost in cinema.—David Cox

Last Days in a Lonely Place

(Phil Solomon, U.S.)

Solomon’s distinguished career as a master of celluloid transformations, both physical and metaphysical, has now extended into the world of video. Who would have thought that the imagery of Grand Theft Auto could be turned into an existential song of mourning for a friend?—Irina Leimbacher

Letter to a Child

(Vlado Skafar, Slovenia)

The passage of man’s life from childhood to old age presents itself through a series of monologues elicited from kids, teenagers, young parents, an elderly couple, an almost senile man, etc. It’s humble, often radically artless, solely concerned with the freedom of its narrators and their silences as much as their insights, their hopes, fears, and dreams. It’s a bridge from the 21st century back to the 19th, constructed from human experiences.—Olaf Möller

Louise-Michel

(Gustave de Kervern & Benoît Delépine, France)

A cheerfully malicious black comedy: when their workplace shuts down, the female staff of a children’s clothing factory pool their resources and hire a hitman to shoot the bastard responsible for losing them their jobs. Yolande Moreau plays the lumbering heroine with a bizarre past and Belgian director Bouli Lanners plays the inept putative killer. Tati-esque pacing, outré non sequiturs, and comprehensive shredding of good taste make this louche road-movie cum buddy romance the most fully realized yet from French provocateurs behind 2004’s Aaltra. A gleefully scandalous homage to the 19th-century anarchist heroine it takes its name from, Louise-Michel is also a political call to unusually drastic direct action in times of recession.—Jonathan Romney

Manila in the Fangs of Darkness

(Khavn, Philippines)

Movie icon Bembol Roco walks the mean streets of Manila as “Kontra Madiaga,” a character invented by combining the actor’s two most celebrated performances: innocent country bumpkin Julio Madiaga from 1975’s Manila in the Claws of Light and death-squad leader Commander Kontra of 1989’s Fight for Us. Haunted by memories of loss assembled from snippets from these and other Lino Brocka films, Kontra’s soul is long dead from butchering resistance fighters, but the Madiaga part of him continues to search Orpheus-like for the girl for whom he came to the capital. Shot from the hip in a single day and shot through with video-quotes from film history, this is conceptual minimalism povera at its most politically edgy.—Olaf Möller

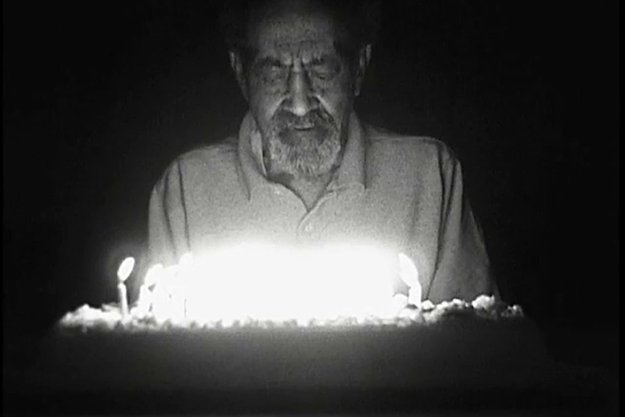

Ninety-Three

(Kevin Jerome Everson, U.S.)

A three-minute gem: a face-off between a life force and aging in a duel between breath and fire, as another birthday comes and goes.—Irina Leimbacher

Our Beloved Month of August

(Miguel Gomes, Portugal/France)

A wondrously single-minded work of two halves from prankster extraordinaire Gomes: in part one, a film project founders due to typical Portuguese summer madness (e.g. finishing a lawn game instead of casting the movie’s lead role); in part two, real life conspires to (re-)create the project’s unrealized story. Putting into play the pitfalls and potentialities of reality and fiction, this is a hybrid work from a radically free sensibility that couldn’t care less about such distinctions. Gomes tells a story about the shadows of a doubt, and it becomes a reality.—Olaf Möller

Ponyo on the Cliff by the Sea

(Hayao Miyazaki, Japan)

With characteristic charm, Miyazaki explains “at Ghibli [studios], we decided to draw Ponyo on the Cliff by the Sea completely with pencils, without the use of ‘electricity.’ That is our advantage.” And so, by refusing to give in to the lure of digital technology, the old master of anime has erected a monument to the traditional unity of genius and craftsmanship, constructing a fable about a boy and a diminuitive sea princess that fuses elements of Greek and Japanese mythology with Hans Christian Andersen’s The Little Mermaid. Complete with pre-digital romanticism and impressionistic animation, Ponyo reinforces Christoph Hüber’s view of Miyazaki’s filmography as one long-form masterpiece.—Manuel Yáñez-Murillo

Prisoner/Terrorist

(Masao Adachi, Japan)

An essay à clef about Kozo Okamoto, the sole surviving perpetrator of the Lod Airport massacre in 1972, carried out by the United Red Army and PFLP. It’s done as a philosophical exploitation-tract on terrorism and a self-realization by a man who went underground and got serious.—Olaf Möller

Revisiting Solaris

(Deimantas Narkevicius, Lithuania)

Donatas Banionis, the lead actor of Tarkovsky’s 1972 Solaris, revisits his role in an adaptation of the final chapter of Stanislaw Lem’s novel, which was omitted from the original film. Shot on the site of a former Soviet television station, and using non-synch sound, Narkevicius’s short rethinks our relation to the film, to science fiction, and to nostalgia for a future that neever was.—Irina Leimbacher

Sparrow

(Johhnie To, Hong Kong)

Shot between more commercial projects over a period of three years, Johnnie To’s Sparrow is another of his love letters to the city of Hong Kong, though this time in a lighter, more lyrical form that approaches the stylization of a musical. Simon Yam, so often cast as a brooding psycho, here ascends to a Cary Grant-ish elegance and charm, as the head of a family band of pickpockets whose timing is ruffled when he catches a glimpse of a beautiful woman (Kelly Lin), who appears to be the unwilling mistress of a local crime boss. Yam and his three brothers vow to liberate her, engaging in a thieves’ duel that climaxes in a pocket-picking contest staged in the rain at a busy Hong Kong intersection. Atypically for To, only one small drop of blood is spilled in the course of the action. Blissful filmmaking, with appropriate accents of melancholy, from the last man standing in Hong Kong cinema.—Dave Kehr

Ten Oxherding Pictures # 3: Viewing the Ox in Tibet

(Lee Jisang, Korea)

The latest feature-length installment in Lee’s Buddhist epic of enlightenment finds a guilt-ridden, memory-haunted man ascending a Tibetan mountain to pray. As always, Lee works with the simplest means possible; the more economic cinema is, the purer it becomes. Eternity is located in attentiveness to the tiniest detail, be it a pixel or a speck of dust—and then that attention transforms into devotion.—Olaf Möller

You, The Living

(Roy Andersson, Sweden)

One of the supreme absurdists of our time, Andersson serves up a series of immaculately conceived vignettes of appalling urban life. Set in a perpetually cold, smoke-diffused Northern Europe, they’re constantly surprising and often outrageously funny. Working in long, static takes on intricate studio sets (a practice developed from a long career making subversive commercials), he challenges his hapless characters at every turn—authority figures are reduced to misery, the forces of good admit defeat, would-be lovers are denied their bliss. One sublime conceit—a honeymoon house that glides through the night like a train—provokes the thought that, for Andersson, in this world always on the brink of disaster, the only true salvation is in our imagination.—David Thompson