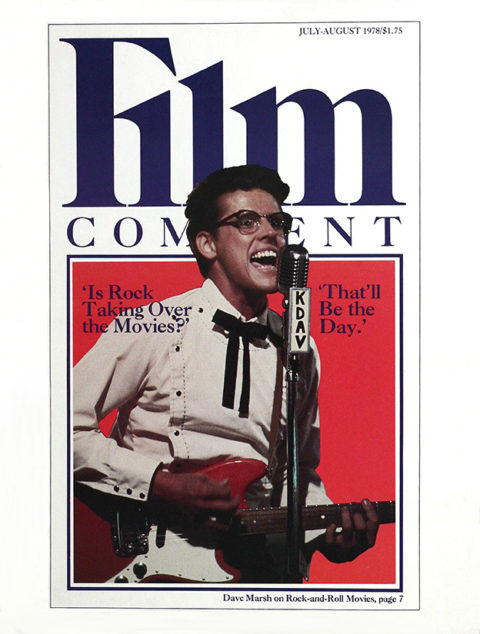

By James Harvey in the July-August 1978 Issue

Sirkumstantial Evidence

The ironist of Hollywood melodrama talks with James Harvey about Marx, Fassbinder, and Lana Turner

Sirk’s extraordinary life has been marked by two abrupt and dramatic departures—at just those moments of dreamlike success that would have prompted most people to try to settle in where they were forever. The first flight was from Hitler Germany—in December 1937—just as Sirk (himself 37) had established himself as a leading director in the German film industry. He traveled to Rome, and from there to America and Hollywood where he was unknown.

Sirk’s next leave-taking, two decades later, was less momentous perhaps but even more astonishing. After having made the most successful movie in the history of Universal to that date (Imitation of Life, in 1959) and gaining the kind of success in Hollywood that very few ever do and nearly everyone else dreams about, Sirk walked away from the whole thing, quietly but firmly. He went to France to do a film on Utrillo, with a screenplay by Ionesco. But the project floundered permanently when Sirk fell ill. And after his recovery, he gave up filmmaking for good, settling in Lugano with his wife, Hilda.

He’s not at all sure, he tells me, that he’s done the right thing. But there it is, he’s done it. And if he misses America, it’s too late now; he is too old to settle again. Both he and Mrs. Sirk assert that they couldn’t tolerate Lugano if they didn’t get away a good part of the year. Each fall, Sirk teaches a film class at the University in Munich. And each summer he figures in some way in the nearby Locarno film festival. He is studying Latin again and reading Hegel. “No one ever reads Hegel finally.”

Magnificent Obsession

For above everything, Sirk—who knew Kafka and Brecht, who was a friend of Max Brod’s and a student of Panofsky’s—is a European intellectual. It’s a vocation that he is once again working at. “For twenty-five years,” he says of the active middle of his life, “I was grazing in arid pastures in this respect.” He tells me a story about the incredulity of a librarian at UCLA when he asked—in the late forties—for a copy of Euripides.

He thinks perhaps the happiest time of his life were those years in the early forties in Southern California when he and his wife (mostly his wife, he emphasizes) ran first a chicken farm and then an alfalfa farm. No, he had oh friends in the film industry—oh, acquaintances perhaps—not even that really. Except George Sanders, who moved in with them and stayed for a year. The only real friends he and Mrs. Sirk had in Hollywood were the people they got to know when they first settled in California. And now—in Lugano—it’s a quality in America that he misses most. “The simple creative generosity that you find in some ordinary Americans.”

“Creative generosity” did not distinguish the German colony in Hollywood however. That extraordinary collection of exiles—with such figures as Mann, Werfel, Reinhardt, Lubitsch, and Lang at its center—was not just a group: being a German in Hollywood was a way of life in those days. What bothered Sirk most about them was their “spite” against America, which amounted in conversation to a group obsession, almost a madness. “To talk constantly about how uncultured, how unlettered, how awful and ugly America was—and they saw nothing, nothing at all. Oh, but no one here knows Dante, they would say. This often from people who themselves had never read Dante, I can tell you they hadn’t. No, no, soon I stayed away. I had to stay away—from their spite.”

Thunder on the Hill

And there is not the slightest hint of sourness or recrimination when Sirk recounts such memories. “And,” he continued, “you know what that spite did for them?” Pause. “They thrived on it.” He bursts into laughter. “They absolutely thrived. Probably it saved them all, you know.” And the idea, of course, delights him.

Today the most vital filmmakers in English, he thinks, are probably Altman, Kubrick, and Bogdanovich. He was very taken with Nashville, but not quite with Barry Lyndon. “A bit too pretty.” When I suggest that the “prettiness” is a deception rather like the surfaces of some of his own films, he agrees. “But it was too perfect, too embalmed.”

We talk about some film stars of the past. He praises Charles Boyer (“What he brings to his role, beyond anything a director could wish or expect—well, it’s simply extraordinary”) and deplores Clark Gable (“That face of a tomcat—what did people see in it?”) His comments on Garbo are surprising; she was never a very good actress, he thinks; her spell never worked on him. “I saw Queen Christina and nothing happened. To me she was just mediocre.”

Sirk stands in a trickier relation to his material—to the studio-assigned stories, scripts, and (often) stars—than any director I know of. Often that relation is an adversary one. An intelligent director confronting the world of Fannie Hurst or of Lloyd C. Douglas confronts not only banality, but an even more virulent kind of falsity: the self-deceptions and consoling lies about life and human character that the tearjerking mode exists to supply us with. John M. Stahl works the same territory but differently from Sirk. Stahl tends to enlarge and transform his material where he can do so. Watching Back Street or Only Yesterday we often tend to forget the genre. But with Sirk’s “weepies” we almost never do. Nor is it part of his intention that we should. Sirk’s Imitation of Life is in an important sense a movie about its own genre—about the genteel pop culture that it itself exemplifies. The characters do live in the world of Fannie Hurst—that is part of their interest for and connection with the rest of us. But we, the audience of the film, inhabit another level as we watch it: the “world” of Sirk’s intentions and attitudes, his famous ironic subtext.

Written on the Wind

But we were always a bit uneasy there. Most audiences, after all, take these films straight. And even the “best” audiences are not always quite sure when they are seeing tackiness, or a criticism of it, an irony, or a mistake, a failure to achieve reality, or an intended unreality, an empty gesture, or a comment on such gesturing. I would resolve such questions in favor of the films, of course, but I would not wish away the uneasiness. For it is by asking just such questions, I believe, that one finds the best way into understanding these films. And that fact alone marks the special audacity and challenge of Sirk.

I should probably say that I had to learn to like the films—and that that is how I learn from them still. When I first saw Imitation of Life in 1959, I thought it clearly a bad film. The idea that any of it might have been, so to speak, intentionally “bad” never occurred to me then. But once I became aware of even the possibility of an ironic intention, I could see it at work in the film in a way that transformed it entirely. So it is precisely because Sirk’s films walk such a narrow line, the awareness of intention becomes especially crucial—and the question of the filmmaker’s own conscious intentions particularly interesting.

Sirk is a unique figure, and most of our ways of talking about him so far have not nearly begun to get at that uniqueness. If he is a major director, as I believe he is, it is importantly because his best work is not easy to like or to come to terms with. But at the least, the mirror-reversals of his surfaces, the almost Nabokov-like density of some of his textures, expand our sense of what is possible in art, and of what is duplicitous too. His films can have an almost unique troubling force. The relation of Robert Stack’s pain to the formal strategies that surround it in Written on the Wind is one of the most disturbing arrangements in modern film—the gesture of both generous and a powerful artist.

Sirk requested that I not use a tape recorder; he believed it inhibited spontaneity. He said he would prefer that I take notes as we talked. He assured me that he would show “the utmost patience” with my note-taking; and he did. What follows preserves the sense and the shape, and—I hope—some of the feeling and sound of the conversation.

Author’s Note: Although Sirk granted the following interview without conditions at the time, he was—to my surprise—very unhappy with the final result. “Too gabby,” he called it, and too personal. He had hoped, I would guess, to be represented by something more formal and considered, a less conversational and more impersonal dialogue. He then wanted to rewrite the interview (as he had done, I understand, with Jon Halliday’s fascinating and indispensable book of interviews, Sirk on Sirk). But since the many revisions he suggested changed it, in my judgment, into something quite different from the conversation that took place between us—and more importantly, offered a version of himself altogether less impressive and engaging than the man I met and talked to—I feel I must stand by my own version of that conversation. And that, the reader should be advised, is what follows below.

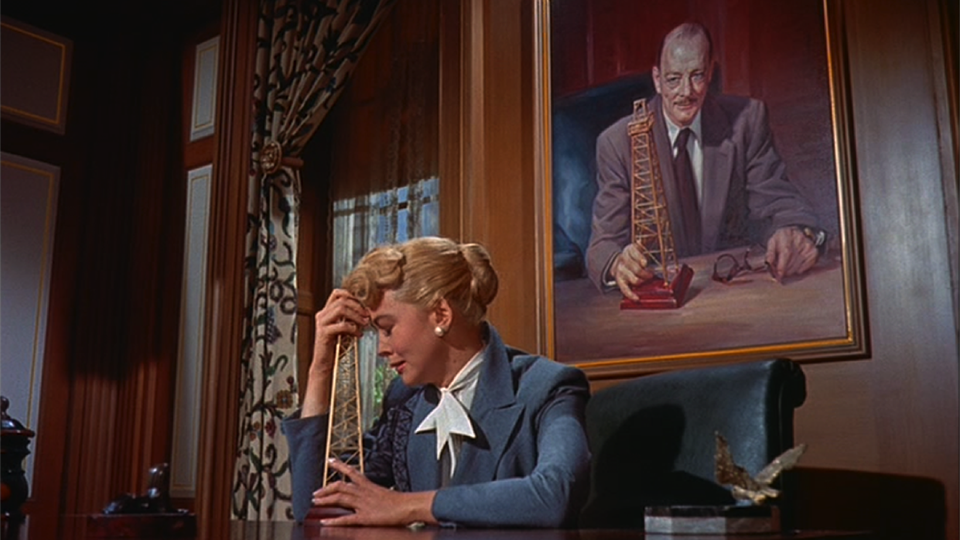

Imitation of Life

Sirk: I never saw my films after I finished the final cut. I never went to a preview. Universal of course did not favor re-takes. And I can’t recall that any of my pictures was affected by the results of a preview. Not long ago Mrs. Sirk and I watched Has Anybody Seen My Gal on television. It was in Italian. And I recently saw A Scandal in Paris—which I think is an excellent picture. Though it was no success, you know. It just barely got back its money. I saw Summer Storm about five years ago. Oh yes—and All I Desire too, after Halliday spoke of it.

But you go to Sirk retrospectives now and again—you don’t watch the films?

No, you don’t watch them. No.

Why not?

Because you don’t like them. Because you get depressed.

I see.

Because you are dissatisfied with anything once you finish it. But a poet, even a playwright, can re-write. Not a filmmaker. And in the studio days you were tied down beforehand by the script. You can change things but mostly in such a hidden way that the studio won’t object.

But as a writer you must know—you are writing a paragraph, you set out in one direction—then you write a sentence or get an idea that changes your whole conception. But if you’re making a picture and you shoot scene eighty-four and you find your conception changing, you are just stuck. You can’t start over, you can’t change those eighty-three other scenes any more.

Take Written on The Wind. I show the climax of the action even before the story begins. The audience sees Kyle coming to that house with the gun and so on, all under the opening titles. Now this I did because my conception of the film changed in the midst of shooting. I couldn’t re-shoot the scenes but I could re-arrange them.

How had your conception changed?

The continuity looked too regular to me. Too linear. I decided to play against the tension of the story—which I always like to do. What can I say? As a director you are building instinctively, almost musically at times.

Did you work with the writer before shooting that film?

Yes, but I’m not sure how regularly. Remember, I was doing three pictures a year at that period.

Anyway the writer is always your comrade, he is your friend. Often he is the only intelligent guy in the whole crowd, the only one you can really talk to.

Certain scripts you get, of course, you just feel hopeless. So you must try to do something with lighting, acting, décor, pace…all those elements. Or else the material is too usual, so you try to find an element of strangeness. In All That Heaven Allows, that scene where Jane Wyman sees herself in the TV set. Or the mechanical man walking across that table in There’s Always Tomorrow.

It’s usual to have a victimized heroine, as you do with the Lauren Bacall character in Written on the Wind. But there is some suggestion, isn’t there, that she is not as innocent as she imagines herself to be—that she was indeed attracted by Kyle’s money?

Definitely. She is ambiguous. That’s exactly why I cast Bacall. Because she has this ambiguity in her face. She has almost a designing quality at times. And people asked me why I didn’t cast a nice American girl type. But I wanted what Bacall has. She has this wavering light about her—and she is not a lover. The whole relation between her and Stack remains ambiguous then. I explained to them both that Kyle must constantly feel that he is losing her. And he is uncertain of her because she really is ambiguous.

Written on the Wind

You described yourself yesterday as a kind of handicraft worker: But surely it’s an odd sort of handicraft, when you so often worked to subvert what you were given. You functioned a lot as an ironist and a subverter.

Yes, yes…

What you do to the message of Fannie Hurst in Imitation of Life for example.

Yes. We played what was between the lines, so to speak.

Were the screenwriters in on that intention? Were they in on the satiric slant?

No. Yes, some of them—yes.

Did Laura Turner or Sandra Dee know that their characters were at all unsympathetic, that the film viewed them ironically?

No. No, actors you shouldn’t tell about technical matters. They lose their innocence. If you tell an actor the character is unsympathetic, he’ll tell you he’s sorry but he can’t do that—strange, but he never has been able to do that, and so on. No no, you should never tell an actor such things. In some ways a director is a bit of a doctor—and he must have a helpful manner with his clients.

Turner’s costumes are very garish; they often seem to be a joke. Was that intentional?

Yes, of course.

Did she care? Or didn’t she notice?

She was very compliant through the whole shooting. She trusted us. And I might add that she wasn’t sorry—she was very happy with the picture.

The producer, Ross Hunter, had a great manner with everyone. He was tremendously successful—very charming. “Oh, but it’s a crude charm,” someone said. Yes, but in Hollywood who will notice if you have a subtle charm? There is one word in the English language, and without this word you couldn’t have an American. This word is wonderful. Now, this was Ross’s word. He used it to everyone, and everyone loved it. He could get anything he wanted.

Some of the sentimental scenes in Imitation of Life seem very surefire to me, very effective in soap-opera terms. They seem devoid of irony. And so I’m not sure at those points what your attitude is.

What scenes?

When Annie finds her daughter at the Moulin Rouge night club and then has to pretend not to be her mother in front of the white roommate. It’s their final farewell scene. And as pathos, if I may say so, it’s extremely adroit.

[Shrugs]

Or the funeral scene.

The funeral itself is an irony. All that pomp.

But surely there is no irony when Mahalia Jackson sings. The emotion is large and simple and straightforward.

It’s strange. Before shooting those scenes, I went to hear Mahalia Jackson at UCLA, where she was giving a recital. I knew nothing about her. But here on the stage was this large, homely, ungainly woman—and all these shining, beautiful young faces turned up to her, and absolutely smitten with her. It was strange and funny, and very impressive. I tried to get some of that experience into the picture. We photographed her with a three-inch lens, so that every unevenness in the face stood out.

You don’t think the funeral scene is highly emotional?

I know, I know but I was surprised at that effect. When I heard how audiences were reacting to that…But that was the reaction of American audiences. When it was dubbed into German, all they got was the Negro angle. It’s true the picture wasn’t a great success in Germany—far from it. Recently a friend of mine was it and he said, “But it’s such a cold film—and there are no sympathetic people at all in it.” So I was surprised at the American reaction…. It may be—I have no talent for sentimentality, so perhaps I simply don’t recognize it.

Imitation of Life

The style of Magnificent Obsession is ironic then?

Yes. Overplaying can be underplaying. In Magnificent Obsession I often did this. When I have Otto Kruger’s face appearing in the glass above Rock Hudson during that operation—that is parody, of course. As I told Halliday about the novel, it’s a crazy plot and that saved it for me in a way. But in the film then, there has to be some parody going along with the sincerity. And that was true of a number of pictures of mine. But Magnificent Obsession has never been one of my favorite pictures.

A whole picture which I kind of liked was Written on the Wind.

Some critics talk about Written on the Wind as if it were a realistic film.

No, it’s even a kind of surrealism. The people are heightened versions of reality—not realistic characters. [Laughs] A European would say, “Strange people these Americans”—if he took it as naturalism.

Above all in its lighting and colors, it is a non-realistic film. Fassbinder wrote a very perceptive thing about my style—he spoke of the craziness of my lighting. He points out that my lighting is never realistic, almost never from where the real light source would be. I was pleased that he saw that.

Remember—Written on the Wind is basically one set. By this very fact then, I am investing—I am contriving to paint with a strange brush, so to speak. Imitation of Life. on the other hand, is much less compact, much richer in scenes and details. But in fact, with Written on the Wind, I had even more opportunity to furnish rooms and interiors lavishly. The studio expected it. But I determined to do the opposite. This material, I decided, is poster material—what you call placatif. And the whole picture is in a kind of poster-style, with a flat, simple lighting that concentrates the effects. It’s a kind of expressionism, of course like Wedekind, or the late Strindberg, or the early Brecht. And I avoid what a painter might call the sentimental colors—pale or soft colors. Here I paint in primary colors—like Kirchner or Nolde for example. Or even like Miro. I have the flashing red of a car and I want that to be just as red as possible.

Some people have commented on the blatancy of some of your symbols. In Written on the Wind the symbolism too is rather poster-like. One critic argues that this blatancy occurs because it is appropriate to the characters—it is they who turn the objects around them into symbols. For example, the boy on the mechanical rocking horse whom Stack sees just after the doctor has told him that he can never have children.

That was not a symbol. Some things in this film are meant to be symbols but not that. No no, I remember—the art director had put a horse in front of the drugstore. So I put a boy on top of it, and he was there when Stack came out of the doctor’s office. That’s all. I never saw any meaning to it at all until Halliday pointed it out to me.

But it gets such emphasis—Stack bugs his eyes at the boy and the music swells.

I don’t want to question your statement, for after twenty years I don’t remember every detail. It was not intentional. In film you have to learn to use what you find on the set. You can never visualize that situation beforehand because it is always different. Once you have finished working with the writer, with the art director, then you must leave yourself perfectly open and flexible. You may get an idea from the last word or the last gesture of the day’s shooting. My first film experience, I worked everything out and nothing worked out. But once I had shed my beginner’s ideas, my stage director’s notions, I never prepared myself too much. Also I learned to improvise on the set—a method I used to some degree in all my pictures.

On the other hand, you can’t get too far away from the story, and you can’t change too much of the dialogue, because the front office will tell you that’s not the thing. You are tied mostly to a piece of trash. Of course it’s quite different for directors now. But sometimes I see these old movies on TV, and they are not so interesting, not so good. Recently I saw an old Bette Davis picture, All About Eve. The role of Sanders as the critic was just silly, I thought. So unbelievable, so overdone—there was no sense of humor anywhere in it. But comedy dates very quickly, doesn’t it? Though some of Billy Wilder’s pictures hold up well, I think. Don’t they?

Your favorite screenwriter was George Zuckerman?

Yes. He was a very gifted man, very flexible. I always encouraged him to write plays. After Written on the Wind and Tarnished Angels, which he did with me, they wanted to make him a producer. That didn’t work out and he went to New York to write for the theatre. That’s when I lost touch with him. He was a man of sensitivity—which is almost the rarest thing in Hollywood. Not long ago I was in a bookstore looking through this book on American screenwriters. I was not very interested, and then I saw his name. It was an interview, and he mentioned me. It filled me with nostalgia. Because I have the feeling that I neglected him. He was unhappy in New York, I know. But at that time I was tied up with the Ionesco project.

The dialogue Zuckerman wrote for Written on the Wind seems rather simplified, rather schematic. Is that right?

I am not sure what you mean by that. Certainly we wanted to get away from sophisticated dialogue. There is more sophistication in Imitation of Life, for example. Speaking of that, probably the most brilliant dialogue I worked with was the script that Ellis St. Joseph did for A Scandal in Paris. In fact, if you talk of art, I consider A Scandal in Paris my best picture—even above the Chekhov picture [Summer Storm]. This picture [A Scandal in Paris] I saw again in Zurich. But it’s a European film really—in a totally European style. So are Summer Storm, and my first American film, Hitler’s Hangman [Hitler’s Madman].

Summer Storm

Why did you simplify the dialogue of Written on the Wind?

Because of the optical style, which as I’ve said was also simplified, stripped down. And also because of the characters and the story. This is a small-town story—about a small-town family which just happens to be tremendously rich. Bacall is more sophisticated, and so is her dialogue. But Stack is sophisticated by his money only—by being in New York all the time, by being at “21”. His approach to Bacall is very primitive. He’s a country yokel really.

Now the character played by Hudson was designed by Zuckerman and myself to be an ambiguous figure. He is so full of goddam typical American naïveté—attractive of course to the sophisticated New York type Bacall plays. Also he is handsome, no doubt he is a good lover. He is the opposite in every way to the Stack character. But he is a negative figure. He is not really a man who has a helpful feeling toward these two degenerated kids, Stack and Malone.

Malone of course wants her innocence again. She thinks she can find it in Hudson. But he rebuffs her in a very cold way. So that everything results in a way from his not deeply understanding—because such understanding is not in him. With his simplicity, his straightforwardness, he is very much a type of the American good boy. Of course most audiences would find him a marvelous guy no doubt, very sympathetic. This is irony. In a didactic way it’s a parody—because two elements are playing against each other. And you are teaching your audience how wrong the right guy is.

But are you? Not if they think you intend him to be marvelous?

You make them feel that he’s not.

What is the audience supposed to feel at the very end of the film—when Hudson and Bacall drive away?

I don’t know, of course, but I imagine they might feel disappointed.

Why? It looks like a happy ending of a very conventional sort.

Disappointed because the richer characters are in some sense left behind. Stack kills himself. Malone is left to that big house with nothing but maybe the pleasures of the bed to console her—because though she is a corpse she is a living one. Maybe the pity of the audience would be so strong they would want Hudson to save her. In any case, how could an audience really pull for two such figures as the Hudson and Bacall characters—who are rather coldish people and not very interesting.

A friend of mine who saw the movie for the first time got the strong impression that the Hudson character actively undermines Stack.

Yes. Definitely. Here is a very accurate reading of the film, by a German critic, Wolfram Knorr. I will translate what he says on that last point. He describes the two main characters as “arrogant, self-satisfied, and naturally full of activity, above all of a wish to please old Hadley. They coldly quit the Hadley house at the end, leaving the poor Merylee alone. All this is designed by Sirk the teacher so that we may sympathize with the two wonderful good-for-nothings…” And so on.

Now, maybe the audience will not see, or maybe fortunately they will note that the director’s heart in this picture is with the two doomed people. But only these two people are interesting, are deeply human.

How did you happen to cast Stack and Malone?

It was almost coincidence. Studio policy at that time was that you put two lesser names with the two big stars. So I was limited to supporting players. I ran a number of pictures and from that I cast Stack and Malone—but purely for their visual qualities. I had no way to know they would turn out to be so talented, such fine actors.

How did you find Barbara Stanwyck when you worked with her?

Oh, very intelligent. Very, intelligent, of course. And a great star. Unfortunately, I couldn’t give her any great parts in those days. And now she is neglected by the American cinema lately. But last winter in Munich, a young man came up to me. He said he was doing a study of Stanwyck—whom he considered the outstanding American film actress. He asked me if I would consent to talk to him about her. I was only too happy and we talked for hours. About this wonderful star.

I did see All I Desire again—after Halliday praised it to me. And you know there is nothing, nothing the least bit phony about her ever. Because she isn’t capable of it. That insignificant little picture she did with me and she played all of it right out of herself. And yet she is so discreet—she gets every point, every nuance without hitting on anything too heavily. And there is such an amazing tragic stillness about her at the same time. She never steps out of it and she never puts it on, but it is always there, this deep melancholy in her presence. I think she is more expressive and resonant than almost any other actress I worked with.

Did you make any changes in the midst of shooting during Imitation of Life?

The funeral scene wasn’t in the original script. So of course the front office was very nervous about okaying it. “Is it against God?” they said. Ross Hunter told them, “Oh it’s wonderful—it’s full of religious touches.” And as usual, he got what we wanted. It was an expensive scene. For the exteriors, outside the church, we had to go to the Paramount lot to build the set—Universal didn’t have the facilities. For the interiors, we found a church in Hollywood.

There's Always Tomorrow

The Moulin Rouge nightclub scenes are remarkable. Were they done on location?

Partly. We did the nightclub show itself in an old movie theater in Hollywood.

It’s all cold and perverse and crazy—and nightmarishly accurate. Especially Susan Kohner’s routine with the lounge chair and the champagne, and the girls riding offstage on that conveyer belt—with the overhead shots that make you think of the camps. And it all looks like a real night club act. Was it? Was any part of it?

No, no. It’s all invented for the film. We wanted to show that she is not right away with the wonderful world of chorus girls and show business—you know? I wanted something with a certain feeling of cheapness about it.

There’s one scene in the movie that puzzles me. I think it works, but still I’m not sure how, or why you made the choices you did. It’s the scene where Frankie [Troy Donahue] beats up Susan Kohner after he’s found out that she’s a black passing for white. It seems very stylized—in a film that is not stylized on the whole. It seems deliberately movie-ish. The set is an obvious fake—you could do a musical number on it. The background music is jazz and blaring. Frankie’s behavior and dialogue seem blaringly exaggerated, and so on.

It’s difficult to remember. Mostly you do such things by intuition, by feeling… as I say, it’s hard to remember. But I think I had a slight feeling that the scene could be lacking in cruelty, lacking in drama, because for one thing it was so goddam short. It had no build-up to it. Yes I definitely had this feeling. I remember that when I saw the rushes, I was a bit doubtful that the scene would come off as what it should be—a scene of utter degradation of the girl. Let me tell you what I told the writer—I don’t remember who it was anymore [there were many writers on this picture]. I said we have to get the feeling that this is not just the boy knocking her down, but society. This is another race, this is another power, you have to represent “Whitey” here. Yes, I was only doubtful it wouldn’t be extreme enough.

You are right. In a way that scene is like Written on the Wind. Expressionistic. It was done with a broad brush and a strong drawing hand. It’s not like the rest of the picture—which is impressionistic on the whole.

How would you characterize the style of The Tarnished Angels?

Not the strong glaring style of Written on the Wind. More related to A Time to Love and a Time to Die. It was rather realistic. I wanted to give an idea of a period long gone. It was strongly conditioned by being in black-and-white, and on a very wide screen. Later on I regretted its not being in color, but at the time I thought I could get that period of the Thirties better in black-and-white.

This picture was not nearly the success it should have been in my opinion. Because of two things mainly—it needed color. Also I think it was a mistake perhaps to repeat so soon after Written on the Wind, this combination of Stack and Malone. But the studio wanted it.

Malone was uncomfortable in this role, I believe. She told me during the shooting that she felt she wasn’t right for it. And when an actor tells you that, it usually means something. The great power that she had in Written on the Wind is really not so appropriate to the girl in Tarnished Angels—who should have more shades.

As you know, it was a long projected scheme of mine to do this novel [Faulkner’s Pylon] on the screen. Subtle maybe it is but it’s lacking in some force, in some optical power. If I were to redo this picture now, I would do the same script by Zuckerman, but I would do it better. Mainly I think the problem has to do with color. The whole carnival business is lost in black-and-white—the death bursting in through the door should be a burst of color, too. And in the racing scenes, those pylons should stand out on the screen.

Your films were never taken seriously in their own time by critics. It must have been astonishing to you to find the career that you’d abandoned taken seriously at last and so many years later.

I didn’t even know that Godard had written about me until Halliday came here. Of course while I was making films I didn’t read reviews. You can’t read them—everyone is saying something different. The first time I had any notion of what you call serious attention was when a French friend sent me a clipping from L’Express in the late Fifties. It said the Academy Awards as usual had slighted the two most important films of the year—Touch of Evil and Tarnished Angels.

When I was directing Ionesco’s Le Roi Se Meurt in Munich, in the mid-Sixties, I got this phone call. Two men from Cahiers du Cinema—could they come to the theatre and interview me? That whole interview took place while I was rehearsing actors, in between the scenes.

Tarnished Angels

Was the recognition a satisfaction at all?

No, I don’t think so. Not much. Anyway you are never satisfied with your own work. Oh, a small satisfaction maybe. The real satisfaction is yourself knowing you have succeeded. Perhaps for that one moment you believe in yourself wholly.

There is a certain kind of artist—the reckless genius. He just shrugs all setbacks off, he is so ultimately convinced that he is bound to succeed. Now Fassbinder has that. I’m not necessarily saying he’s a genius—but I personally think he is—but he has that kind of confidence in his own talent. And in Germany, he needs it.

The Germans are specially unforgiving to anyone who leaves. When Fritz Lang came back they cut him to pieces. And Marlene Dietrich—who is not only a great star you know, but a great woman—told me in Hollywood after her German music hall tour, that she would never go back again. And I don’t think she has. Now I understand they have made a very vicious film about her.

Or take the case of Remarque in Germany. I don’t know what you think of his work—maybe it’s good, maybe it’s not so good—but there is one fact about it. Remarque was the one German writer who was known from Tokyo to Paris—he represented Germany to the world. But the Germans never forgave him for leaving.

You said before that the real satisfaction comes from knowing you’ve succeeded. Do you recall having that satisfaction while you were in Hollywood?

I don’t think so. I believe the satisfaction being felt was by Mrs. Sirk mostly. I’m a skeptic—by temperament I’m a pessimist. Of course there are rare moments. Certainly I felt some satisfaction of a kind when the president of Universal told me they were all indebted to me—for giving them the biggest moneymaker in their history. How almost a whole people could switch from one moment to the next, almost completely. The younger people one could forgive perhaps—the attraction of something new, etcetera. But the older people—and the intellectuals. Because without the intellectuals, Hitler might never have made it to power.

That’s just the point at which you chose to leave Hollywood.

I couldn’t go on making those Ross Hunter pictures. I needed more freedom. The Utrillo picture was my way out—my French bridge to something else, I thought. Then I got ill. Which I took as a sign that I should get out of the picture business. Always, you know, my mind listens to my body, and my body listens to my mind. That’s why I’ve survived so many tyrannies. Even Hollywood.

Sometimes I think the whole Hitler thing changed me into something I might not have been otherwise. As you know, my wife is Jewish. And basically all my friends turned against me when Hitler came to power. And I still don’t understand it. I will never understand it.

How almost a whole people could switch from one moment to the next, almost completely. The younger people one could forgive perhaps—the attraction of something new, etcetera. But the older people—and the intellectuals. Because without the intellectuals, Hitler might never have made it to power.

There was a historian of importance, some twenty years older than I was—but a close friend in those days, and a liberal. He gave a dinner party, which Mrs. Sirk and I attended. And another friend, a pianist, was playing for us, when this man’s son came in. We knew this young man, he was an assessor of law—but we weren’t prepared for what we saw that night. He was wearing an SA uniform. I can still see the glaring red and yellow of that awful uniform. “Heil Hitler,” he said, he saluted us and went out. Then his father—and he knew exactly what he was saying—smiled at us and said, “He looks wonderful in his uniform, doesn’t he?”

As I say, I still don’t understand. It seems even now so incredible. A nightmare. And then too, my career was really broken by the events of those years. If you are a writer, maybe you can wait things out. But if you are a director, it’s different.

To continue reading, purchase the July/August 1978 issue.