By Stanley Crouch in the September-October 2012 Issue

Public Enemy

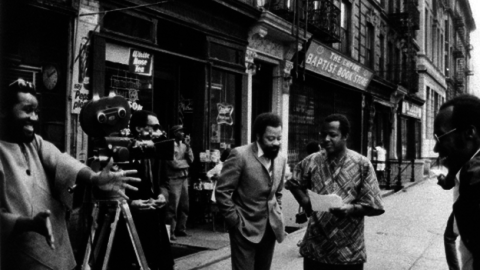

In the restored 1950 adaptation of Richard Wrights Native Son, the author himself plays his protagonist—without sugarcoating him

To accurately discuss Pierre Chenal’s uncut 1950 film version of the novel Native Son, made in Argentina and starring its author, Richard Wright, we need to think about the context in which this film, like 1947’s Crossfire, and 1950’s No Way Out, faced up to certain truths that were not being addressed at the time. These truths about race in America have usually been most melodramatically delivered since then, with self-righteous overstatement rather than high cinematic quality. In our electronically layered modern age we have sometimes been forced to conclude that, in a mottled masterpiece like D.W. Griffith’s 1915 The Birth of a Nation, wonderful things can be messed up by propaganda. Despite its epic impact and unprecedented expansion of cinema’s vocabulary in the silent era, certain things are no less true just because of the discomfort that accompanies them. From Griffith, we learned a grim fact about modern times: aesthetic genius can be interwoven so powerfully with a surrealistic big lie that a stereotypic factoid is actually seen as a fact. From the moment it becomes profitable, mass media will submit to and accept its buffoonish conventions—in this case, racist stereotypes that remained in place until at least 1950. Even though the dream machine recognized No Way Out with Academy Award nominations, Native Son, which distributors butchered according to the rules of the cinematic game of the time, was little noted.

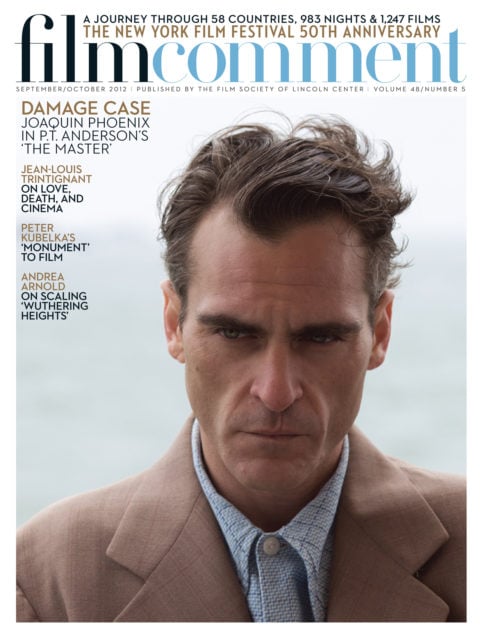

From the September-October 2012 Issue

Also in this issue

To get to it very bluntly, Native Son is not a great film because too much of what it is about exists in the off-screen world; conversely, writer-actor-director Orson Welles’s Touch of Evil is the real thing. Every shot, every camera position, every bit of dialogue, every piece of cloth and material used in costuming and set design, is part of the shadow-driven conventions of film noir but achieves a geometric vibrancy that goes beyond the genre, which is why the film deserves the overused term “great,” far more often claimed as an advertisement than aesthetically achieved. But that’s show business.

Native Son

Even so, Native Son handles itself quite well as a very good film for a number of reasons. The presence and rhythm of the actors in the lower-class black community and the upper-class white community come forward as much more real than contrived. Richard Wright plays Bigger Thomas as a knucklehead who measures himself in a variety of ways. He does this by bullying his girlfriend, by leading a small, petty criminal gang, by taunting for his own enjoyment his sister’s fear of a dead rat by shaking one in her face, by submitting to white people he feels smarter than even if they are economically above him, whether left-wing liberals, condescending white men of the press, or authority figures from the police to the justice system. They amount to imbecilic lames as far as he is concerned, and he is as often right as he is wrong. That fluctuating difference is what makes him a tragic urban character, not an urban legend.

Wright’s Bigger Thomas is quite related to the all-American lower-class rebel who sees material resources and homespun smarts as the answer to everything. He does not believe in education, aristocratic blood, or class. Force will do. In some inferno, he would be comfortable exchanging points of view with James Cagney’s Tom Powers from Public Enemy or Humphrey Bogart’s Duke Mantee of The Petrified Forest. In the latter film there is Slim, the black member of the criminal gang who tells a “faithful” chauffeur among their hostages that he should not be so submissive to “MISTER Chisholm.” Bigger was already brewing. He was ready to pop not as a tart but as a poisonous dart.

Native Son

In that sense, Wright was more interested in human types within an American context than he was in clichés about class and color, no matter how well intended they were. His vision went beyond lockstep ideology. He proved that in the full version of his mutilated 1945 memoir Black Boy, which he originally intended to be titled American Hunger (Ralph Ellison told me he had read it in full form while in unedited manuscript, strongly suggesting that it was one of the literary fathers of Ellison’s complexly assertive Invisible Man). Mississippi-born Wright was ambivalent about the left and shows that again in his screenplay and in his performance. For the occasional mastery of the film noir vocabulary, the unexaggerated human fire, empathy, and tenderness that now and again arrive, and the unpredictable and suitably mysterious qualities of human motivation that spill outside of clichés and ideology, Native Son is well worth seeing. The full uncut dose is an affirmative example of how much human clarity was wished for and was given a damn good foot in the right direction of whenever any chance came along. Kicking a field goal in show business is never less than very, very hard. After living through the shining effects and the dark defects of Hollywood, from then until now, we should all be able to acknowledge that observation as a fact invincible to any sentimental bleaching. There it is.

Native Son screens February 11 and 14 at the Museum of Modern Art.