President Barack Obama returned from Argentina this week with a piece of film history in his suitcase. During his visit, the President was gifted with a digital restoration of Native Son, the 1951 film adaptation of Richard Wright’s landmark novel of race prejudice in the U.S., shot in Argentina and starring the author himself. Directed by Belgian Pierre Chenal and featuring studio recreations of the tenements of Chicago’s South Side, Native Son was radically cut to appease North American censors and for six decades was available only in truncated form.

President Barack Obama returned from Argentina this week with a piece of film history in his suitcase. During his visit, the President was gifted with a digital restoration of Native Son, the 1951 film adaptation of Richard Wright’s landmark novel of race prejudice in the U.S., shot in Argentina and starring the author himself. Directed by Belgian Pierre Chenal and featuring studio recreations of the tenements of Chicago’s South Side, Native Son was radically cut to appease North American censors and for six decades was available only in truncated form.

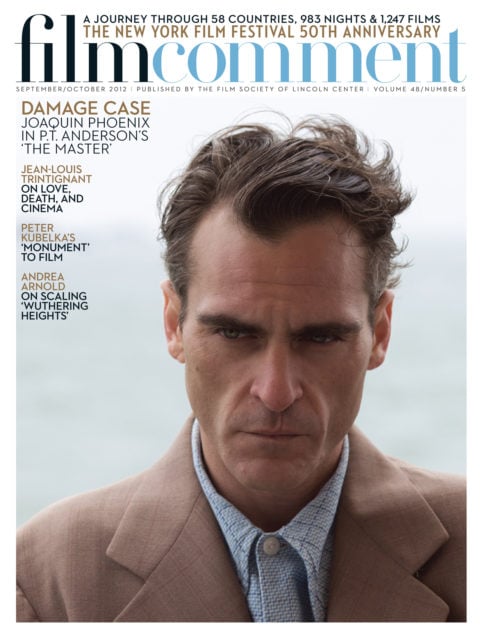

The gift which Obama brings home represents a major restoration effort undertaken by the Library of Congress, in consultation with Edgardo C. Krebs, using a 16mm print discovered by Argentine film historian Fernando Martin Peña and a 35mm print from the National Archives in Puerto Rico. The restoration was screened in the Masterworks section of the 50th New York Film Festival in 2012.

Wright, who spent 10 years and his own money bringing Native Son to the screen, despised the bowdlerization of his work, which understandably failed to connect with North American audiences. The 104-minute digital restoration was presented at the International Film Festival of Mar del Plata in October 2015, with Krebs’s book Sangre Negra: breve historia de una pelicula perdida. Krebs calls the film “certainly the most meaningful link that Argentina has with the Civil Rights Movement.”

It is dismaying to read accounts of Pierre Chenal’s 1950 film Native Son. Whether in biographies of Richard Wright, or in American critical appraisals, everything about it is considered a mistake, a preordained, predictable mess. Wright in the role of Bigger Thomas; the place where it was made (Buenos Aires); the reconstruction of Chicago streets and South Side black homes on the soundstages of Argentina Sono Film; and the very fact that it was produced by an Argentine studio and directed by a Belgian. It would take too long to list the numerous errors and poor research that are pervasive on all of these points. But it is significant that none of the film’s confident critics had seen the original, complete film, only the butchered version permitted by U.S. censors. More than 60 years since it opened in Buenos Aires with great success, Native Son is still known as this other film: the crippled version, created by censors and disastrous reviews. Together, they have sealed the fate of this effort. The uncut film, however, and the history behind it, are far richer than people realize, and deserve a second (or, to be more accurate, first) look.

My first acquaintance with Native Son was indirect. I was doing research in Paris on the Swiss-born anthropologist Alfred Métraux. A friend and colleague of his, Claude Tardits, told me in passing that Métraux had often had breakfast with Richard Wright, because both lived on the same street (Rue Monsieur le Prince). Their association made sense. Both shared an interest in Haiti and in the Négritude movement. Métraux had been considered by the Carnegie Corporation as a candidate to write the classic 1944 text on race relations ultimately assigned to Gunnar Myrdal and published as An American Dilemma: The Negro Problem and Modern Democracy. Wright and Métraux participated in the creation of the influential journal Présence Africaine, in which many distinguished African intellectuals published anticolonial essays in the Fifties. And Métraux headed a study at UNESCO that took direct aim at segregation by debunking the notion of a scientific justification for racism. All of these preoccupations would have resonated viscerally with Wright.

It was through another friend of Métraux, the filmmaker Jean Rouch, that I learned for the first time about Chenal’s Native Son. The complete version of the film appeared at first to be lost. Then, in the search for a print, a great breakthrough came when I met Argentine film historian and collector Fernando Martin Peña, well known to cinephiles for having found 25 minutes of additional footage of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis. It so happened that in the Nineties he had also discovered a complete 16mm copy of Native Son and written an excellent article about it for a Buenos Aires film magazine.

A second unexpected breakthrough came in conversation with the late Bolivian director Jorge Ruiz, considered by John Grierson to be one of the six most important documentary filmmakers in the world. (His Vuelve Sebastiana and Mina Alaska are almost miraculous feats of storytelling.) Jorge was very familiar with Native Son because his friend and onetime associate Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada—they co-founded the first Bolivian film company—had been assistant director to Chenal during the shoot at the Argentina Sono Film studios. Sánchez de Lozada, who was twice elected president of Bolivia in the 1990s and early 2000s, had just graduated from the University of Chicago when he arrived in Argentina hoping to find a job in the movie industry. He is the only surviving member of the production team on Native Son. One of his unofficial duties was to help Richard Wright get around Buenos Aires, where the author was very popular.

Everybody involved in the filming of Native Son knew that they were doing something difficult. Wright had to eliminate certain passages of the text for his novel to be published by the Book of the Month Club in 1940, and Orson Welles and John Houseman’s 1941 theater adaptation was also complicated: Houseman and Wright had to conspire to rewrite Paul Green’s initial rendition to keep the characters and text more faithful to the book. Green only learned about the changes to his script on opening night.

Chenal has written that it was clear to him that adapting the book in the U.S. was impossible in the 1940s and 50s. When he arrived in Chicago to shoot contextual scenes, accompanied by Richard Wright, the producer, Jaime Prades, and a minimal crew, Wright was denied admission to the hotel. Chenal proposed that they all move to a different one, but Wright laughed it off. Looking at the sky, he said, “Home sweet home.” It was dangerous too for American actors to get involved. Even an expatriate like Don Dean, the American band leader—who was originally from Oklahoma but had married an Argentine and settled in Buenos Aires—was warned by his mother not to do it. (Dean plays Max, Bigger Thomas’s lawyer.)

But when production on the shoot got underway, it was not a second-rate effort. Chenal was convinced that “Dick [Wright] had transformed into Bigger Thomas. The hero spoke through the mouth of its creator.” (You do not have to act, he told Wright, you have to live Bigger’s nightmare.) Chenal had worked before with Argentina Sono Film, one of the most important studios in Latin America, and he did not lack for technical equipment or professional expertise. Both he and Wright were fastidious about ethnographic details. The set had to look and sound like Chicago. The products on display in shops, advertisements, and billboards within the film were authentic. Wright had a picture of Jackie Robinson pinned to the wall of the ladies dressing room in the club were Bessie Mears sings. (Worth noting is the participation of dancer and ethnographer Katherine Dunham in the musical score—a story that deserves its own telling elsewhere.)

The topic was not a new one for Chenal, or for Argentina. Native Son was translated by one of the country’s leading publishers, Sudamericana, just one year after appearing in the U.S. In 1944, the great expatriate Spanish actor Narciso Ibáñez Menta led a production of the Welles-Houseman stage adaptation in Buenos Aires. Chenal, also an expatriate at the time, was very impressed by it. When the opportunity arose a few years later to undertake a movie version, he was ready.

Chenal and Wright were aware of some important constraints, and made a few compromises accordingly. The script followed quite faithfully the Wright-Houseman theater version, but certain things were altered. The scene in which Bigger Thomas kisses Mary Dalton was left on the cutting-room floor—Chenal and Wright probably assumed that, with so much money invested in the project, they could only go so far. The bedroom scene remains chilling enough as it is. Aside from their visual and narrative merits, the two flashbacks that explain Bigger’s murder of his girlfriend Bessie, with their nightmarish atmosphere reminiscent of a De Chirico painting, were conceived by Chenal as a way of taking the unsparing stare of the camera off Wright, who Chenal felt could not carry the weight of those dramatic scenes without help.

Sangre Negra, as it was titled in Spanish, was a box-office and critical success in Buenos Aires, boosting Chenal and Wright’s hopes that the film would have a good run in the U.S. and Europe. Those hopes were quickly dashed. Walter Gould, the American distributor, entered into an impossible struggle with censors and 30 minutes were cut. Gould went to court in Ohio, where the Board of Censors had refused to license the film for public exhibition on the grounds that it “. . . contribute[d] to racial misunderstanding, presenting situations undesirable to the mutual interest of both races . . . undermining confidence that justice can be carried out [and presenting] racial frictions at a time when all groups should be united against everything that is subversive.” Among the scenes that were cut figured one in which a white mob gathers outside the courthouse where Bigger’s case is being tried. Clenched fists are seen. One of the men says: “Where I come from, we don’t waste time trying a nigger, we just lynch him.”

Both Chenal and Wright despaired about the way their film was essentially cornered and finished off. They could do nothing about it. Wright moved to France, where he expanded his interests and joined a broader struggle. Chenal was buoyed to a point by critics who had seen a partially restored, 90-minute version of the film at the Venice film festival and judged it worthwhile for a public of cinephiles. “I pass on to them the responsibility,” he said.

San Francisco–based film noir expert Eddie Muller, to whom I showed the complete 104-minute version, commented: “I’ve been asked many times ‘Were there any noir films about African-Americans?’ and now, thanks to the rediscovery of Native Son, I can honestly say ‘Yes!’ Its literary pedigree aside, Native Son is genuine noir in its moral ambiguity and existential despair. It’s fascinating to see all the genre conventions and stylistic flourishes we associate with noir being brought to bear in a racially charged drama about African-Americans—made contemporaneously with the classic noir era in Hollywood. The recovery of this film gives us an essential and previously missing link in mid-20th-century cinema.”

Thanks to a collaboration with the Library of Congress’s Motion Picture Division, a fully restored version of Native Son will be available soon. This is bound to change the way the film has been understood. Its merits and complicated history will at last be properly examined and granted a fair hearing.

Edgardo C. Krebs is an Argentine social anthropologist and a researcher at the National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution.