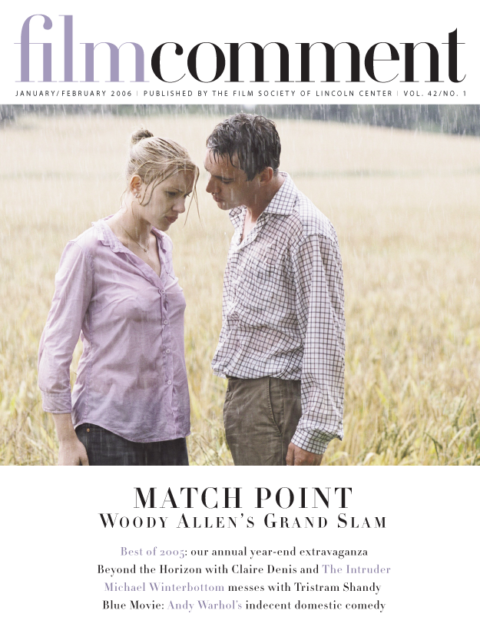

Manderlay

Your latest film, Manderlay, is a Danish-Swedish-British-French-German-Dutch co-production…

Really?

That’s what the credits say, yes. Now the film could indeed be read as a European declaration of distrust against the United States.

Well, you can read anything as anything, as you know.

You certainly encourage different readings of your work, don’t you?

I hope so. In Denmark my film has been seen very much as a traditional look on racial problems in America. But, of course, I am happy if it can be read in more ways than one.

But the one way all the world seems to want to read Manderlay is: anti-American—or, more specifically, targeted against Bush’s policy in Iraq. Is that an interpretation that you wanted to provoke?

No, not at all. First of all, the Iraq War wasn’t on when I wrote the film. The film is based on historical research. But its theme, although dealing with American racism, is more universal: a story like that could take place anywhere really. But it is fiction and, as you can see, not shot in America. I’m quite sure that Alabama doesn’t look like the locations in my film.

It must have been quite hard to cast American actors for Manderlay.

Not the white parts but the black ones, yes. Extremely difficult.

Was the script too hard to digest or the image of U.S. history too negative?

Probably both, but there was another reason why it was so hard to find a prominent black actor to do Manderlay: there’s a reason why certain black actors have made it in America. I don’t mean that in any negative way. Within any group of underprivileged people, only some are capable of being successful under the conditions of the privileged. The ones who make it are able to somehow fit into the white system. And it is very difficult to give this privilege up. We actually talked to well-known black actors who told us they would not risk giving up the privilege of success to do a film like Manderlay. They said they were very happy that the film is going to get made, but they dare not be part of it. I do not want to tell you who that was, but there aren’t that many prominent black actors of Danny Glover’s age. The reason why Danny finally, after long discussions, wanted to do the film, is that he’s very much into politics. That’s his whole life. But it takes so much courage that even with Danny it was difficult. It is dangerous stuff somehow, even if it’s hard for us Europeans to see.

Manderlay

Having black presidents in TV series also seems to show and prove: they can only exist there, in Hollywood dreamland, never in real life.

Exactly. It’s completely ridiculous. We will never see a black president, yet they are all over TV.

Glorifying black people only in the entertainment world prevents us from socially upgrading them in real life?

Probably. And it’s simply a lie: there is no black president. So what good does that do? It only sounds politically correct, but it’s not a reality.

How long did you prepare before writing the screenplay?

I did not read a lot, but we had many historical advisors onboard. I trusted them. Our story is all based on second-hand information, anyway—and it will be just that for most Americans seeing my film.

When Dogville opened you were harshly criticized for doing an “American trilogy”—without ever having been to the United States. Have you been there since?

No, and I don’t really plan to do so, since I have a problem getting onto a plane. I try to see it as an advantage that I have not been to the States. I cannot go back in time, anyway. Of course I see things in a different perspective. But sometimes things can be even clearer when you’re farther away. And my trilogy is fiction, after all-not a documentary on the USA and its people. Let’s say I’ve taken the clichés and made them up to play against each other. I am twisting clichés, that’s what Manderlay is all about.

Do you want people to be entertained by your films? Or, rather, enlightened?

I don’t know if entertainment is the right word for what I want. It’s hard to say. Some of the films I love were definitely boring the first time I saw them.

Like what?

Well, the first time I saw Barry Lyndon, I fell asleep three times. After that, I saw it another 20 times, and I loved it more and more each time. Sometimes art is not so easy to digest.

Who do you direct films for?

I do not think I work for an audience in that sense. You can only work for yourself-and maybe see yourself as an audience.

Manderlay

Your producers do not keep reminding you that you actually have to work for an audience?

No, otherwise they would have told me earlier on that I shouldn’t stage the film on a black floor with some chalk on it. But, you know, I am very lucky to have many good distributors around the world. And they need to be fed also: that’s my only concern. As you can see from all the co-producing partners: financially, my films are euro puddings—hopefully without looking like that. But my distributors have to also stay alive somehow. I guess they will all be happy when the black-floor period is going to be over.

The last entry in your trilogy, Wasington, is going to be directed in the exact same style as Dogville and Manderlay?

That is the idea, yes. And that does not sound very entertaining for me as well-to do that a third time… But then I have a feeling it would be more mature if I just stick to the plan.

You have to be consistent here.

I believe in this form, you know? I feel good about it. Manderlay is a little bit too nice, maybe. The problem about it is that if you do things more than once they tend to get boring. But you also get too good at it. Manderlay is too clean, too perfect, story-wise also.

Dear Wendy, a film that you wrote and Thomas Vinterberg recently directed, also deals with America. Is that a side product of your trilogy?

No, not really. The script is quite old. My version of Dear Wendy was very much a love story: a man and a gun. That seemed interesting to me. I am actually a hunter myself, even if I don’t do it often enough these days. You have to do things a lot to be good at them. And I do too many things already: I’m playing more tennis now, go on fishing trips. You can’t do everything. To me the fascination of a gun’s power is not that I feel like shooting anybody, not even animals. There’s no fun in killing an animal, but the hunting itself is fun. Shotgun hunting is a little uncivilized, very noisy, but if you go after a small deer for maybe three days and finally kill it with one shot-that is like De Niro in The Deer Hunter. If hunting is done right, it’s very clean and nice, actually. Of course, you’re killing an animal…

… but it’s painless.

No, I don’t think so. No matter how you do it. But it’s also not painless to be a cow in a stable and be slaughtered. I would actually prefer to be a wild deer and be shot in the woods: not a bad way to go maybe. But painless? That’s also an illusion. We want to believe that everything is painless. But it’s not.

A question about your actors…

Is it painless to be acting in my films?

Manderlay

No, I’m actually changing the topic here. Is it true that you keep telling your performers to cut away 90 percent of their acting? You always go for understatement?

Difficult question. It is pretty simply always about being able to accept a performance—or having to reject it. To overact a scene is actually very good for understanding intention and character. If you do not understand that, it is impossible to overact. So it’s great to start with overacting and then tone down, but to still keep the essence. That takes time.

As highly stylized exercises, Dogville and Manderlay seem so sparse and ascetic at first glance—and yet they induce fascination rather than boredom. How do you do that?

That’s something you do, I think. Any audience will do that. If you go along with a given story, this fascination will always be there. That’s just the nature of being an audience, of seeing and listening: you want to tie things together, you want to see things alive. Remember, as a child, when you had a book with a few drawings in it-you wanted to see those creatures alive, to be drawn in by their story.

Everything in those two films—the scenery, the sets, the narrating voice-seems destined to take away illusion, to minimize naturalism. Still there’s identification, emotion—and also illusion. Do you think reductionism eventually produces the other extreme: even more emotion?

It could, yes. As kids we all had those very simple toys that did not look like anything, yet were very precious to us—or the game that we all played, where you’re drawing a house on the sidewalks to playfully live in. This could be infinitely better for children than expensive toys or full illusionism. If things get too explicit, you get tired of them. If you only had a perfect model train, you probably didn’t play with it for very long. What can you do with it? There’s no real freedom in it. You want to use your imagination.

On the other hand, your style of editing is very punchy, very gestural, very physical—very “documentary,” if you will. Do you spend a lot of time in the editing room?

Oh yeah. When we shoot the film we are simply collecting enough material to be able to play around with in the editing phase. We shoot quite a lot-and since it all is video, you can do that with no limits. I do 50-minute shots sometimes.

Manderlay

Do you believe in realism in cinema?

No, that again is an illusion. But I believe in life.

An imitation of life, rather.

Sure, there’s nothing real about cinema. This handheld camerawork of mine, incidentally, is not about imitating life. It goes back to these fundamental and very complicated questions: where do we place the camera and why? There are no specific rules for that, only conventions. When I ask myself why I do certain camera movements or setups, I find out that this pointing manner in which I use the camera is a direct translation of my own curiosity: what interests me? Who do I want to look at or listen to? There is always some personal logic to where the camera goes. There are reasons.

But that’s not necessarily more realistic. This freewheeling “documentary” camera is a fake, of course, an old trick.

Yes, but that doesn’t mean that you can’t try that method. I believe—as we did with the Dogme movement—in working on location, in unchanged places, with actors wearing their own clothes. That provides a film with so many gifts that it becomes alive. Something happens that cannot be planned. And it’s the same with my handheld camera: it is something that shouldn’t be planned. That was my big problem on Breaking the Waves: the camera operator wanted to learn those movements. But then they lose their vitality. So even though the mobile camera is obviously fake documentary, it still contains more truth to me because it can’t be planned. Strictly there’s no truth at all, of course. But even documentary is not “true.” My camera style also has a lot to do with taste and a lack of grammar—and it’s a result of my earlier heavy storyboarding and working with cranes.

Nevertheless your U.S. trilogy is a sharp move away from Dogme: you are actually excluding all traces of real life by hiding away in this dark room, this black stage.

Oh yeah, I’d like to make things collide: all the sounds for example are very naturalistic. And that’s decidedly not to explain things. Usually sounds explain far too much. Normally a train in films always has this cartoonish train sound attached, even though I think it would be easy to record real train sounds that do not sound like film trains at all. That I tried to do in my films: to find a sound that is the opposite of the drawing of a house saying “a house.” We tried to find sounds that do not really represent things that do not explain themselves properly. So Manderlay is theater, yet we have those strong filmic elements: handheld camera, close-ups. We get a fusion of very different things.

Manderlay

You have been publicly stating that everything that has been said or written about you is a lie.

Well, isn’t it? Everything is becoming a lie once it’s being manipulated. You know, I am being asked all the time about how cruel I am with actresses, how arrogant I am, and stuff like that. That’s not how I see myself. I cannot relate to that. Of course I got angry when Björk wanted to bankrupt the company during the shoot of Dancer in the Dark.

She did?

Oh yeah. Yeah. Every day she threatened to leave the set. And, of course, you get mad because that really hurts; you begin to have nightmares. Am I going to lose everything? Will the film never be finished? Fuck. But she was very good when she was working. God, we fought. But I don’t think that makes me a sadist. It’s a very natural reaction to stress, right?

As a director, isn’t it completely impossible to be sweet-tempered all the time, anyway?

Sure, you have to be authoritarian somehow, but I actually try to do it in a very Scandinavian way. To work well, I simply need good relations, especially with the actors. Contrary to other directors, I cannot work when there’s a war going on.

But then how were you able to finish Dancer in the Dark at all, with the war going on?

I honestly don’t know. Björk kept saying that she did not want to do the film, right from the beginning. It was ridiculous. I wanted to fire her. She screamed, “You can’t fire me”—it was all completely crazy. But somehow, this last scene when she is hung, I remember that very clearly, she didn’t want to see the gallows before at all-and then she played the scene extremely well. After that I said to her, when she was lying there, hyperventilating: could you maybe take out the second line of the dialogue and replace a certain word with another? Everybody thought, okay, now she will explode and die for real. But she didn’t say anything, we filmed it again-and she did it. Exactly right. She was really far out then, that wasn’t acting or feeling or whatever, but she was still, as a musician, completely in control.

Dancer in the Dark

But she wasn’t always like that.

No. There was one scene where I simply couldn’t take it anymore. I was literally running away. She shouted, “How can you leave me when I have to commit this murder—”we were just doing that in close-up. Then she said, “You can’t leave me alone in this suffering.” It was wild. But you know, Iceland and Denmark have a troubled history, so maybe that’s also to blame. And people from Iceland are just plain crazy. All of them. That’s a fact.

In the media, it’s usually rather you being portrayed as either pretty neurotic or especially mean or calculatedly provocative. Are those just stereotypes?

Well, there’s some truth to it, of course, but not the whole truth. I’m sure, for instance, that Björk really believed I was pushing her. And I was, because she was pushing me. And I have a lot of phobias—the reason why I talk about them is because that way it’s the easiest for me. It’s not that I particularly like to talk about my phobias, but I have them and it’s extremely unpleasant.

Sadism is, in fact, at least thematically, a driving force of many of your films. Why are you so obsessively working on stories of torture and rape and exploitation? Because you’re a moralist?

Maybe, but also because I’m a filmmaker, and those topics are the fuel that films can live on. And you know what? Those themes are really the regular stuff in cinema. Take one of the usual Bruce Willis films: he will always be treated really badly, otherwise there would be no story. That’s just normal—and nobody would call the director of one of those films a sadist.

Right, but heavy violence is rather rare in art house films.

Maybe so. The whole technique that I use in any film is to go to the edge of things. When I try out a new method or a new subject, I always want to see how far I can go with it. How far can I go with the characters and the drama?

Radicalism always generates emotions, that’s for sure. You enjoy to crush your audience, especially with those less-than-unhappy endings.

Yeah, I like feel-bad movies.

Dancer in the Dark

Is there anything to be learned from being depressed?

I’m against pedagogic cinema. But endings really are difficult. Those artificial happy endings, they just aren’t good enough, you know? I want endings that somehow resist to end the film.

You quite surprisingly gave up directing Wagner’s monumental Ring tetralogy for the Bayreuth festival in 2006. Did you really lack the strength to do that or was it just an excuse?

Of course my ambition was to do the Wagner that would destroy all other interpretations. I worked on that for two whole years. But I realized that technically it would be so difficult, there was no way to realize my plans on stage. The four operas were not too big for me, only the way I wanted to stage them. If you know that you could only succeed with 30 percent of what you set out to do: that’s not good enough. So I decided, unwillingly, to end my work on Wagner.

What would it have been? Something very cinematic?

Oh yeah. Lots and lots of technology.

In a recent interview your colleague Thomas Vinterberg called you “a very lonely man.”

Well, aren’t we all?

He also remarked that he thought you were born at the wrong time. What did he mean?

Thirtieth of April? Because it’s also Hitler’s death day? No, I have no idea.

In 1991 you started a film that should be ready in 2024. You wanted to shoot three minutes every year. Is that project still on?

No. I have abandoned it. I think we should put the material on the Internet for everyone to use it. It’s like with the hunting: you just can’t do everything. It’s only one of my many unfinished projects. I have to admit that I’m only human, even if I struggle to be more than that. You have to be realistic at some point. Otherwise you keep making a lot of nonsense. But sometimes it’s a victory to give in.

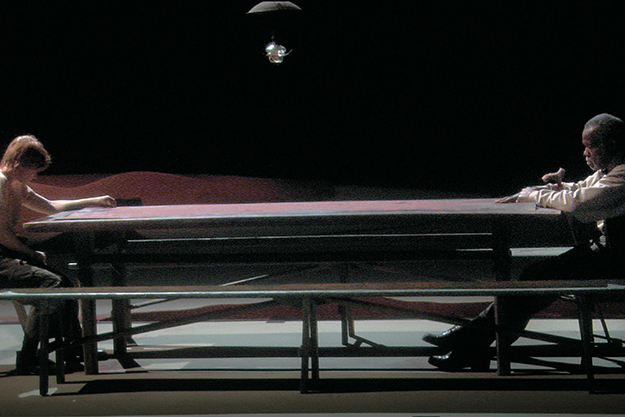

The Five Obstructions

You once stated that one of the complaints you had against your parents was that your upbringing was “too free” for you, that you missed stricter rules. Did you feel you had no guidance at all?

Now that I am a parent myself I can say that it is necessary to provide some guidelines. I’m not very strict, but the difference is I am able to take a minimum of responsibility. When I was very small and in fear I frequently asked my mother if I had to die tonight; she would say, “I don’t think so. The statistics clearly say that you won’t but, of course, I can’t be sure, because anything can happen in this world.” I tell my children: “No. That cannot happen. Just sleep.” It’s just a matter of how much inconvenience you are willing to put on your shoulders instead of living up to your honorable idea of truth. Because if my kids die, I take that on me. If as a parent you are not willing to even do that, to employ this small lie for your child: with parents like that you easily get the feeling that you’re not really loved, even though today I believe I was. It’s a question of ideology.

This yearning for rules certainly infuses your films. The Five Obstructions for example is a film about rules and how rules can alter art, people, and ultimately-the world.

To set up rules can also be a loving act, after all. I’m not saying it always is. Most of the times it’s the opposite. But it can be.

Dogme also was nothing but a game with rules.

Although most of those rules were really only meant for myself. I mean, some of the rules Thomas did. I forget which ones, but most of them I targeted against myself, against the areas I felt I already was too good at, against the filmmaking that seemed too easy to me. It was not only to make things harder but to make the product better by making it harder to produce.

In that sense your films are extremely private.

Yes. But I believe in privacy. Or rather, I believe in specialization. When I watch TV and this strange man appears on screen promoting a product that you’ve never even heard about, then all of a sudden TV becomes enormously interesting. I prefer specialized narration to the popular form of narrowing everything down so that everyone can understand it.

Many of your films are about believing. You are religious yourself.

I am a Catholic, yes. I got baptized only 10 or 15 years ago because my parents were non-religious.

The Five Obstructions

Why did you join the church?

I guess I wanted to be religious. But that doesn’t mean that I am. I saw Catholicism as being much more of a healthy religion than Protestantism. I know this is difficult to understand for people who have to live under Catholicism. But as a Protestant you simply have all this guilt and will never get rid off; as a Catholic you can. That’s kind of practical. You say your Hail Marys and all your sins are forgiven. That’s wonderful.

Do you go to church?

Well, no. But I do pray: I say selfish prayers—do not let this happen to me and my children, that sort of thing.

Do you educate your children religiously?

No, they have to make up their own minds about religion. That is quite important to me. And I am not sure if I really believe. It’s so difficult for me as a logical human being not to see any religion as man-made, for a purpose. This is so hard, because it’s very obvious. But maybe this is just another way of testing us.

Next April you’re going to be 50. Afraid of the date?

No, not at all. I mean I do not particularly like getting older, but it was a fact from the day I was born. With each day you’re one day closer to death. That’s how it is. I don’t think death is so bad once you are dead. It’s just something you have to get over.

It’s well known that you adore Carl Dreyer’s work, and that you find Bergman’s films fascinating. Is there anything contemporary that you like?

I don’t see anything anymore. I think you either see films or you make them. I defend myself with the claim that I don’t want to be distracted by other films. Which to some degree is true. Let’s say—which I don’t think—that I fell completely in love with some new technique: I have my basis and I want to navigate from there. I don’t want to do Matrix for a change.

Manderlay

Could that also be fear of further complication? Since it is complicated enough as it is?

Somehow I feel that there have to be people like me who have to keep on going south. Let’s say we arrive at this new land and we send out a man southwards-like in this battle game, Age of Empires—I don’t know if you play that on your computer, I play it all the time. Now if this man saw some films in cinema land and he changed his direction to north, then we can’t use this man. I respect the people who have always followed their nose-even if sometimes they may not have succeeded with their films. But they are not trying to please like everybody else.

Is making films after 25 years still as interesting to you as in the beginning?

Yeah, but the problem is to keep it that way.

That’s why you set up new challenges for yourself with every film.

Actually, at Zentropa we are currently setting up a small lab for the directors—with an editing room, a camera, some lamps, and a little computer. And I’m so fascinated by that because even though it’s low-tech it’s a room for experiments and playing around. You can stay young that way. Yesterday I found—now that is also completely banal—a little helicopter in a toy store, where I wanted to buy something for one of my sons. A remote controlled helicopter. Right now I am learning how to use it, which is extremely difficult. It’s almost like a real helicopter. And I’m just dreaming of putting a little camera in there. I would so like to try that, even though I know it’s silly. Because I think that really might help me understand why and where to put the camera.

That is still the all-important question for you.

Yes, absolutely. It’s constantly on my mind. Answers like: you have to see the face of the hero closer in that scene to see his reactions-that’s not good enough. The camera as the stand-in for the spectator? Doesn’t satisfy me. Why can’t the camera do a certain move? Because you get sick of seeing it? So? Those reasons are simply not enough. Filmmaking to me has to be a pleasure, a play. Only when you derive satisfaction out of playing with cinematic forms a film can become really good. I am really longing for that little editing table, because you can play with the images yourself there, without an editor. Just see what happens when you put two things together, to re-invent all the time is fun. Really. It can make you so happy. This helicopter made me so happy. I bought it straight away, even though I couldn’t afford it, but it is so fantastic. It flies indoors! If you’re good at it you can land the thing right over there, in this room.

So for you cinema is all about visual, sensual attraction?

Yeah, and actually this fascination comes from mechanics somehow.

Manderlay

Technics shape aesthetics.

I guess so. When I was a kid I was building a camera crane, out of wood, just to have this movement. It felt so good.

But great films can also be very simple, very low-tech. Take Dreyer’s Gertrud.

But think of that film: those long, long slow movements? Lit by those tiny lamps? Very nice. I talked with Dreyer’s director of photography, Henning Bendtsen, about that for quite some time. It’s a rare film. Thank God.

You often operate the camera yourself. In Manderlay you are credited together with your DP, Anthony Dod Mantle. Are most of the shots in Manderlay yours?

Almost all of them, actually. Anthony did one scene, I think. On this little comedy of mine called Direktoren for det hele that I will be directing very soon, before I start work on Wasington, I will do all camera work myself. And I needed training for that, because I’ll be shooting that on 35mm. When we did Dogme we had long discussions about my rule that even 35 always had to be handheld. The others claimed that it couldn’t be done, that it was too heavy. So now I am proving that it is possible.

Sounds like torture again.

Oh yeah, torture is fine, as long as it’s only physical pain.

Especially if it’s your own pain.

It should be. I enjoy that, indeed.

Will the comedy be the start of a new trilogy?

No! I hope not. But honestly: I don’t know. All the other trilogies evolved, almost against my will. It’s like when you are out running, and you mean to run two kilometers and suddenly you decide, no, I’ll run five. And that’s normally just before you finished the second kilometer. Suddenly it’s become a five-kilometer run, even if you had no idea it would.