By Sam Di Iorio in the May-June 2003 Issue

Chris Marker: The Truth About Paris

Reconsidering Le Joli mai’s investigation of French social attitudes in the early Sixties

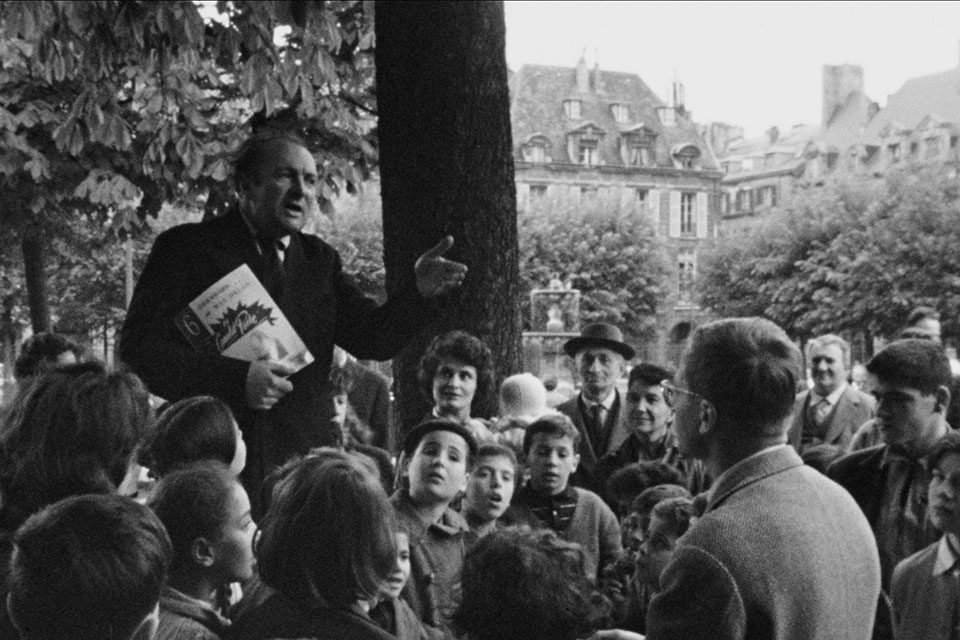

Located in the gray area between personal essay and objective document, Chris Marker and Pierre Lhomme’s 1963 film Le Joli mai is both a tender portrait of a city and an indictment of a way of life. In addition to being one of the key works about the French reaction to the Algerian war, the film is also a far-reaching meditation on the relationship between individual and society, one that corresponds to the leftist social vision elaborated in much of Marker’s work. For a number of reasons (not the least of which being that the video currently circulating in the U.S. is missing a significant portion of the original film), none of this might be evident to the casual viewer. Understanding Le Joli mai becomes easier once the film is places within the larger currents of French culture in general and Marker’s career in particular.

From the May-June 2003 Issue

Also in this issue

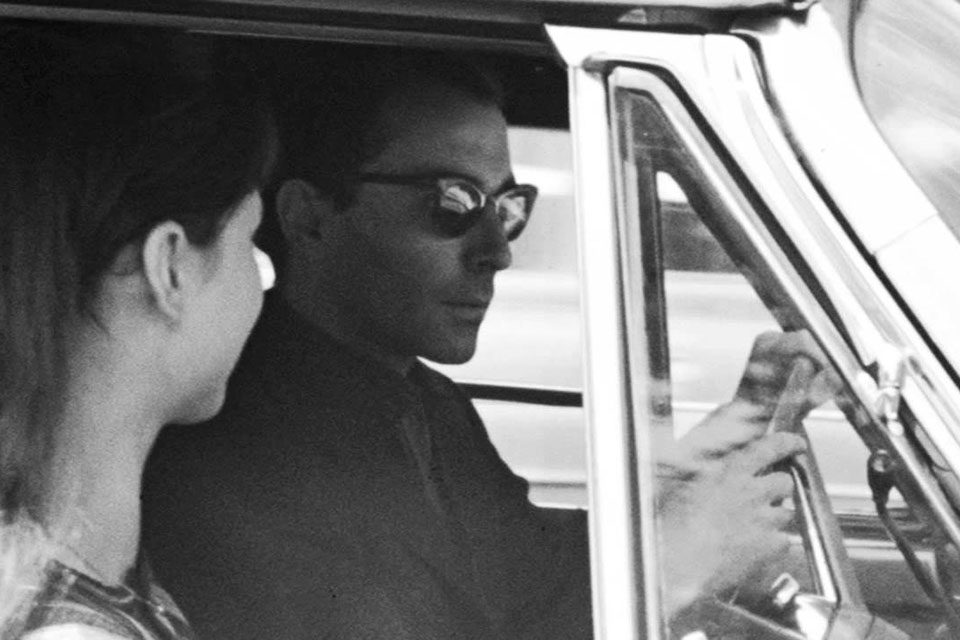

When Marker and Lhomme began filming on May 1, 1962, they started out in the shadow of illustrious predecessors. The previous year had seen the release of a film with exactly the same point of departure. Jean Rouch and Edgar Morin’s Chronicle of a Summer was the influential portrait of the Parisian everyday responsible for the slow-burning cinema verité revolution of the Sixties. Rouch and Morin effectively transformed French filmmaking by introducing new technology (a prototype of the Coutant-Éclair 16mm sync camera made especially for the film) and a new filmmaking style (cameraman Michel Brault was flown to France from Canada to shoot some of the most ambitious scenes). Using a lightweight portable camera, it was now possible to film sound and image simultaneously in practically any location. These innovations heralded a new kind of informal, improvised cinema in closer contact with the real world.

Le Joli mai’s professed goal was identical to that of Chronicle: Marker and Lhomme wanted to use emerging technology to create a portrait of everyday Paris. While recognizing their debt to their precursors (in homage, they even include a brief shot of the self-proclaimed Martin and Lewis of ethnographic cinema), in practical terms they made a very different film. Whereas Chronicle tracks the personal journeys of a small group of protagonists over a number of months, Marker and Lhomme wanted to organize a shorter time span around a wider scope of events. If Rouch and Morin’s film focuses on individuals, Le Joli mai is edited around themes.

Le Joli mai

By the end of May, Marker and Lhomme’s team had accumulated 55 hours of footage, which they cut down to shorter montages lasting from seven to 20 hours. The film’s actual running time is a matter of some confusion. Although the French version of Le Joli mai is just over two and a half hours long, the print circulating in the U.S. is more than 30 minutes shorter: a significant amount of material has been removed. Several scenes have been trimmed (one of the film’s key sequences, an interview with a young Algerian, is missing its final segment) and others completely eliminated. Here are some of the things U.S. audiences have not seen:

A sincere and affectionate portrait of life on the Rue Mouffetard, one of Paris’s most tightly knit popular neighborhoods,

Two architects in a vacant lot criticizing the dehumanizing aspects of modern housing and sharing their dream projects. One of them, inspired by Babar the Elephant, imagines an ideal community of cities in the trees.

An interview with Lydia, a costume designer who admits that she fears others and prefers to spend her time indoors designing outfits for her pets. IN what is undoubtedly one of the most outlandish cat scenes in Marker’s filmography, we see part of her spring collection shown off by a surprisingly patient feline model.

Rehearsals for La Femme sauvage, a play by Algerian writer Kateb Yacine.

An interview regarding the French army’s use of torture during the Algerian war.

A discussion with students from the prestigious prep school Janson de Sailly that takes place during target practice. Marker and another interviewer criticize the students’ naively elitist political stance.

A folk concert at the Théâtre Mouffetard. Agnès Varda, Armand Gatti, and Alain Resnais are all in attendance. Gilbert Samson’s song of a homesick soldier is intercut with footage of the prep school students being trained to shoot and radio messages from French soldiers in Algeria to their families.

As the above list demonstrates, the U.S. print is a much less political film. Although the exact reasons for the cuts remain unclear, they were presumably made to make the film more marketable to foreign audiences. The same issues that once seemed to French for overseas markets, however, have grown in importance with each passing year. It is a shame that the full version of this invaluable document remains out of reach for English-speaking spectators.

Le Joli mai

Despite serious disparities in content, the general approach to Paris in both versions is the same. Ultimately, Le Joli mai is a film about montage. As many have recognized, Marker is a filmmaker obsessed with editing: in his case, the term must be understood in its broadest sense. Not only is he concerned with how shots are linked together, he establishes tension within individual shots through idiosyncratic combinations of sound and image. Le Joli mai marks a turning point in his career since it further complicates this intricate relationship. It is a bridge film that simultaneously looks back the early travelogues and forward to later political vérité works like À bientôt, j’espère. If his first films bear the unmistakable stamp of a singular commentary, the later ones are often collaborative efforts that move closer to their subjects and incorporate a number of distinct voices.

Halfway between these two periods, Le Joli mai is based around a principle of limited dialogue. Marker and Lhomme wanted to open the cinema to the complexities of spontaneous speech generated by ordinary people. At the same time, this guileless testimony was not unconditionally accepted. Rather than naively showing the world “as it is,” they insist on retaining a critical approach strongly marked by subjective presence. As critic Roger Tailleur perceptively claimed, Le joli mai is not cinema verité, it is cine ma verité: not a cinema of truth, but one that expresses a personal take on truth. This individual viewpoint is primarily revealed through montage: when a pair of engineering consultants become insufferably pompous, images of yawning cats interrupt their conversation. The truth about Paris is revealed not through single images but through a combination of shots. Via editing, the sheen of the everyday is stripped away and the deeper concerns that condition contemporary society are revealed.

It’s safe to say that in May 1962, Paris was harboring a great deal of anxiety. Le Joli mai was made as France was nearing the end of a brutal eight-year war with Algeria, which was trying to gain its independence after more than 100 years of French colonization. The film takes place during “the first springtime of peace,” that is, after the signing of the ceasefire accords on March 19 but before the official referendum for independence on July 1. It’s important to point out that violence continued despite the March ceasefire. During the month of May, ten to 50 Algerian citizens were killed every day by pro-French terrorists.

Le Joli mai

Algeria’s slow and painful struggle for independence threw France into a severe crisis of conscience. Hesitant to see the end of a profitable colonial empire, the government was unable to resolve the conflict. Not only did its continued indecision bring the country to the verge of political collapse, its tacit sanction of the French army’s use of torture during the war seriously called into question the republic ‘s moral foundations. As it realized the extent of the army’s oppressive tactics, France’s image of itself was seriously damaged.

In addition to this international crisis, Paris’s domestic situation that May was uneasy at best. The news wasn’t all bad: in the first place, growing economic prosperity undercut the political tension. By 1962, France was finally throwing off a legacy of postwar penury to become a nation of avid consumers. Nevertheless, as strikes and changes in government continued, the public’s faith in its social institutions decreased. Le Joli mai also testifies to another emerging uncertainty. During the Fifties, the French government had instigated the most radical attempts to restructure Paris since the 19th century. In an ostensible attempt to improve the quality of life in the city, whole neighborhoods were torn down and their inhabitants forcibly relocated. By 1962, it’s evident that these changes in urban space were beginning to produce a certain anxiety: the old Paris was disappearing and it was difficult to predict what would come next.

All of these factors—increased economic prosperity, the Algerian war, changes in the urban landscape, internal political strife—inform Marker and Lhomme’s complex portrait of Paris. While Le Joli mai is a relentlessly political film, politics must be understood here in its widest sense, as the framework through which individuals relate to a larger community. The film denounces France’s apathy to the Algerian war, but this apathy is also taken as symptomatic of a larger deficiency. Parisians seem to have closed themselves off from others: the city has lost its identity as a community. Le Joli mai attacks Parisians for their disengagement, for their racism and classism, for their self-obsession in the face of injustice, and for their silence. This distanced critique, however, is balanced with empathy: the film’s harsh conclusions are mitigated by unmistakable affection.

Marker and Lhomme’s urban portrait is haunted by the utopian portrait of an egalitarian society in which individuals live with rather than against others. The hallmarks of this film—its emphasis on the social, its interest in dialogue, its political conscience—became the foundations for Marker’s work throughout the Sixties. From this point on, he drew closes and closer to specific political struggles in France, embracing the local in order to further the larger cause of global revolution. This idiosyncratic verité portrait of 1962, then, can be considered a direct springboard to the militant cinema of 1968. One May contains the seeds of another.

Sam Di Iorio is finishing a Ph.D. in French at the University of Pennsylvania. His dissertation, entitled Everyday Optics, deals with Marker and other filmmakers.